Quentin Tarantino is undoubtedly one of the (if not the) most influential American film directors of the last quarter-century. His gritty, ultraviolent, fast-paced, and impeccably hip writing style and visual eye have made a mark on both underground and mainstream film like no other. Following the one-two punch of 1992’s Reservoir Dogs and 1994’s Pulp Fiction, Hollywood was (and arguably still is) flooded with style-aping films that could be referred to as Tarantino-esque. Indie filmmakers of all stripes have surely benefited from the increased exposure that his quick ascension gave to subterranean cinema.

The weird thing about Tarantino’s influence, though, is that it is derived from his own pop-cultural cherry-picking: Every film he’s directed or written has been loaded with countless homages, lifts, and references to books, movies, TV shows, and music that coalesce into a pop-cultural galaxy of their own. When these references and influences are considered as a whole, it’s easy to see the connections that exist between stylistically opposite corners of Tarantino’s filmography. In a 1994 Los Angeles Times profile that ran shortly before the release of Pulp Fiction, Tarantino professed an artistic impulse to “steal from every movie I see,” and although the discussion regarding what “stealing” is in relation to his catalogue still rages on today, his giddiness when it comes to expressing his omnivorous taste through film is more than apparent.

We’ve put together a comprehensive-as-possible encyclopedia, organized chronologically by film and alphabetically within each (and lumping together both volumes of Kill Bill), of every homage and direct reference to pop culture that Tarantino’s put in his work — as well as an addendum of general influences on his career that he’s acknowledged over the years. Some notes before you dive in:

• We included the two screenplays authored solely by Tarantino — Tony Scott’s True Romance and Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn — but films that he worked on but didn’t have final credit on, like Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, where he opted for a “story by” credit after his script was rewritten significantly, have been excluded.

• There are a lot of notations regarding which elements of scores from other films have appeared in Tarantino’s films, but one composer whose work has been featured hundreds of times over is Ennio Morricone. Morricone is mentioned in this encyclopedia, but every instance of him has not been catalogued for reasons of length (this list would be twice as long as it already is — and as it is, it’s pretty long).

• There’s a huge difference between stated influences and influences derived from film-criticism theorizing, so for the sake of coherence, we’ve stuck to the former and ignored the latter, with very few minor exceptions.

• Unless referenced otherwise, a sizable amount of the interviews cited here were taken from Gerald Peary’s compendium of Quentin Tarantino interviews — and not to be a shill or anything, but if you’re a fan of Tarantino (or just interested in the way the guy talks about film), it’s a must-read.

GENERAL INFLUENCES

A Better Tomorrow II: John Woo’s 1987 shoot-’em-up movie made a big impression on Tarantino when it came to orchestrating the climaxes of his own films: “I was watching it with a buddy of mine, and it’s all building to this big climax. We hadn’t seen this movie before, so we didn’t know they were going to have the biggest shoot-out in the history of film. My friend turns to me and goes, ‘If they don’t get naked and boogie at the end of this movie, this has been for nothing.’ He was right! Doesn’t matter that we enjoyed everything leading up to the end, it had to end in like a big way or it was all nothing!”

All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers: In a 2004 interview with Entertainment Weekly, Tarantino referred to this 1972 Larry McMurtry book as “one of my favorite books of all time.”

Assault on Precinct 13: In a 1996 interview with Don Gibalevich, Tarantino cited the classic John Carpenter film from 1976 as something he’d see “wherever the hell it was playing” when he was younger.

Bande à Part: Classic 1964 film from Jean-Luc Godard (with an incredible credits sequence) that gave Tarantino’s production company, A Band Apart, its name.

Blow Out: Tarantino described Travolta’s performance in this 1981 Brian De Palma classic as “one of my favorite performances of all time” in a 1994 interview with Manohla Dargis.

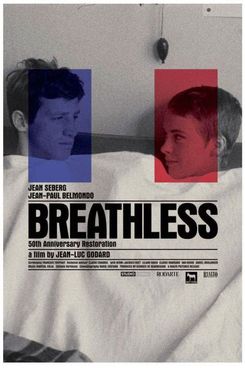

Breathless: “I love Breathless,” Tarantino told Michel Ciment and Hubert Niogret in a 1992 interview in French film magazine Positif, naming it as one of two Godard films that influenced his taste in cinema (along with Bande à Part, obviously).

Cage, Nicolas: One of Tarantino’s favorite actors of his generation: “I don’t think I’ve seen another actor in the history of film that made a career of being miscast and rising to the occasion,” he told The Village Voice’s J. Hoberman in 1996.

Caged Heat: In a 1992 interview with Positif, Tarantino cited this 1974 Jonathan Demme movie as a film that left an impression on him when he was younger, “When I started to develop … my aesthetic.”

Carlin, George: In a 1996 interview with J. Hoberman, Tarantino cited the late comedian as one of his favorite stand-up acts.

Coffy: This 1973 Pam Grier film was the first of hers that Tarantino saw when he was younger, according to a Jackie Brown press conference in 1997.

Corbucci, Sergio: In a 2009 interview with Screencrave, Tarantino referred to this Italian filmmaker as “the other master,” alongside Sergio Leone: “I think my films are closer to his than to Leone’s.”

De Palma, Brian: In a 1992 interview with Positif, Tarantino described his early acting lessons (including six years under James Best, who starred in several Samuel Fuller films) before admitting, “I didn’t fit in with the rest of the actors in [Best’s] school … my idols weren’t other actors. My idols were directors like Brian De Palma.”

Griffith, Charles B.: In a 1993 interview with Graham Fuller, Tarantino described himself as “a fan” of this screenwriter, who contributed to several Roger Corman films.

Enter the Dragon: 1973 Bruce Lee classic that was a formative influence on Tarantino’s younger self when it played at Carson Twin Cinema, a favorite childhood hangout, according to a 1996 interview with Don Gibalevich.

Five Fingers of Death: 1972 kung-fu film that was a formative influence on Tarantino’s younger self when it played at Carson Twin Cinema, according to a 1996 interview with Don Gibalevich.

Le Doulos: In a 1994 interview with Gavin Smith, Tarantino referred to Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1962 film as “my favorite screenplay of all time … I know when I go see a movie and I start getting confused, I’m emotionally disconnected, I check out emotionally. For some reason I don’t in Le Doulos.”

Leone, Sergio: “I never felt gypped when Sergio Leone ended every Western he did with a showdown,” Tarantino told Roger Ebert in a 1994 interview about the massively influential spaghetti Western director, after being asked about how Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and True Romance all essentially conclude with gun-brandishing face-offs. “That’s just the way they ended. But every single one was different.”

Marty: When a pre-filmmaking Tarantino was taking acting classes, he rewrote a scene from the Paddy Chayefsky–scripted classic from memory to perform as a monologue in his class; he told told Fresh Air host Terry Gross in 2009, “[I]t was the first time somebody complimented me [on my writing].”

Morricone, Ennio: Legendary film composer who contributed to Tarantino’s forthcoming The Hateful Eight, as well as provided a substantial influence throughout Tarantino’s career — to wit: His music appears all over Kill Bill. “To me it sounds like rock and roll, even Morricone music,” he’s quoted as remarking about surf music in Jeff Dawson’s 1995 book Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool.

Once Upon a Time in the West: In a 1992 interview with Positif, Tarantino claims that it was Leone’s 1968 Western that appeared on the TV when he decided to “become a director.”

Parks, Michael: Tarantino once referred to the actor (who appears in From Dusk Till Dawn) as “one of the greatest actors that has been produced in our lifetime!” in a 1996 interview with J. Hoberman.

Penn, Sean: One of Tarantino’s favorite actors of his generation, for his “sheer sexual-violence charisma,” he told J. Hoberman in 1996.

Polanski, Roman: Tarantino cited Polanski’s brief appearances in his own films — specifically, The Fearless Vampire Killers and The Tenant — as inspiration for his inclination to appear in his own films in a 1992 Positif interview.

Pryor, Richard, That Nigger’s Crazy: In a 1994 interview with J. Hoberman, Tarantino cited this comedy album as “the closest to a perfect comedy album ever. It’s the Great American Novel done as a comedy routine.”

Ride in the Whirlwind: One of two films from director Monte Hellman (who was also a producer for Reservoir Dogs) that Tarantino described in a 1992 interview with Positif as “[one of the] most authentic Westerns.”

Rolling Thunder: “Whenever I’d read it was playing at the Palace Theater in Long Beach on a triple feature with The Howling, and something else, I’d take the bus to Long Beach to see it,” Tarantino said in a 1996 interview with Don Gibalevich regarding the 1977 revenge film.

Roth, Tim: One of Tarantino’s favorite actors of his generation, for “his versatility and ferociousness,” he told J. Hoberman in 1996.

Scott, Tony: Besides penning True Romance’s script for him, Tarantino has gone on record many times as an avowed fan of the late director, citing 1990’s Revenge as a particular favorite in a 1993 interview.

Shadow Warriors: Tarantino referred to this 1980s Japanese cartoon as “the best cartoon I’ve seen on the screen” in a 1994 interview.

The Shooting: One of two films from director Monte Hellman (who was also a producer for Reservoir Dogs) that Tarantino described in a 1992 interview with Positif as “[one of the] most authentic Westerns.”

Speed: Tarantino cited the 1994 Jan de Bont actioner as “a totally fun movie” in an interview from that year: “Situation filmmaking at its best, because they really went with it.”

Towne, Robert: Tarantino referred to this screenwriter in a 1993 interview as “[deserving of] every little bit of the reputation he has.”

When the Lights Go Down: Tarantino read New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael’s 1980 book at 16 and, according to a 1992 interview with Positif, “[I] thought, ‘Someday maybe I’ll be able to understand a movie like she does.’”

Witney, William: In an interview with Henry Louis Gates, Tarantino referred to this late film-and-TV director as “one of my Western heroes.”

RESERVOIR DOGS

Ali, Muhammad: One of the legendary boxer’s many famous quotes (“If you even dream of beating me, you better wake up and apologize”) is paraphrased by Mr. White (Harvey Keitel) in the opening moments of the film: “You shoot me in a dream, you better wake up and apologize.”

Au Revoir les Enfants: How could Louis Malle’s classic, brutally sad 1987 drama about children attending a private school in Holocaust-era occupied France bear any specific influence on, of all things, Reservoir Dogs? According to a 2013 Variety interview, the title of Reservoir Dogs itself was inspired by patrons at the video store a pre-fame Tarantino worked at — Manhattan Beach’s Video Archives — mispronouncing Au Revoir les Enfants’ title at the counter. Inspiration comes from the strangest places!

Bedlam, “Magic Carpet Ride”: Cover of Steppenwolf’s original recorded specifically by this Nashville band for Reservoir Dogs.

The Big Combo: 1952 crime noir featuring a scene where a police officer is tortured and interrogated by a few of the film’s criminals. In other words, inspiration for the film’s infamous ear-cutting torture scene.

Blue Suede, “Hooked on a Feeling”: This Swedish pop group’s 1974 cover of B.J. Thomas’s 1968 single plays in the car as the criminals drive to the scene of the heist.

Brando, Marlon: “Undercover cops gotta be Brando,” LAPD force member Holdaway (Randy Brooks) tells Mr. Orange (Tim Roth). “To do this job, you gotta be a great actor, naturalistic. You gotta be naturalistic as hell.”

Breathless: The 1983 American remake of Godard’s original, specifically — where, according to a 1992 interview, Tarantino got the inspiration to put a Silver Surfer poster on Mr. Orange’s wall.

Bronson, Charles: The legendary tough guy’s role in the 1963 classic The Great Escape is referenced in the “Like a Virgin” conversation featured in the film’s opening scene.

Chan, Charlie: Harvey Keitel, in his role as Mr. White, snidely tosses out the name of novelist Earl Derr Biggers’ fictional, heavily stereotypical Chinese-American detective character while riffling through mob boss Joe Cabot’s (Lawrence Tierney) old address book.

City On Fire: This one’s a tricky one, since Tarantino publicly dismissed claims made by movie mag Film Threat in the early ‘90s that Reservoir Dogs borrowed heavily — almost to the point of plagiarism — from Chinese director Ringo Lam’s 1987 actioner. Wanna decide for yourself? Look no further than “Who Do You Think You’re Fooling” (above), a 1995 short made by writer/filmmaker Mike White examining shot-by-shot comparisons between the two films.

Day, Doris: The popular 1950s and ’60s actress who’s name-checked by Cabot in conversation with Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen).

Delon, Alain: In a 1992 interview, Tarantino said he likes Reservoir Dogs’ title because “it sounds like something in an Alain Delon movie of Jean-Pierre Melville … I could see Alain Delon in a black suit saying, ‘I’m Mr. Blonde.’”

The DeFranco Family, “Heartbeat, It’s a Lovebeat”: The 1973 single name-checked by Mr. Pink (Steve Buscemi) as one of the songs he heard during “K Billy’s Super Sounds of the ’70s Weekend.”

The Duellists: One of a few movies Tarantino saw Keitel in as a teenager that eventually led him to cast the actor in Reservoir Dogs.

Fantastic Four: Mr. Orange pulls out a (quite timely — for 2015, anyway) comic-book reference to the superhero team that features “that invisible bitch” and “‘flame on’ and shit” while describing what Joe Cabot looks like: “Motherfucker looks just like the Thing.”

Fingers: One of a few movies Tarantino saw Keitel in as a teenager that eventually led him to cast the actor in Reservoir Dogs.

Francis, Ann: One of two actresses incorrectly identified as the actress in the title role of Get Christie Love! in Reservoir Dogs.

The George Baker Selection, “Little Green Bag”: 1969 single from Dutch curios the George Baker Selection that plays over the opening credits of Reservoir Dogs. Fun fact: The original title of the song was “Little Greenback,” which is for sure relative to the interests of Reservoir Dogs’ protagonists.

Get Christie Love! 1974 detective TV show discussed in one of several pop-culture-loaded conversations featured in Reservoir Dogs.

Grier, Pam: The other actress (and future Tarantino collaborator) incorrectly identified as the actress in the title role of Get Christie Love! by Nice Guy Eddie in Reservoir Dogs. “I’ve been a big fan for a long time,” Tarantino said in a 1997 interview, citing The Big Bird Cage, Coffy, Fort Apache, the Bronx, and Black Mama White Mama as some of his favorite films of hers.

Holmes, John: Deceased ’70s porn star mentioned during the “Like a Virgin” conversation featured in the opening scene of Reservoir Dogs.

Kansas City Confidential: 1952 crime-noir film about a bank heist gone wrong that served as an influence for the plot of Reservoir Dogs.

Karina, Anna: The jewelry store the criminals attempt to knock over is named Karina’s, after the Danish-French actress who was once married to French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard.

The Killing: Stanley Kubrick’s 1956 noir that Tarantino claims was a major influence on Reservoir Dogs: “I didn’t go out of my way to do a rip-off of The Killing, but I did think of it as … my take on that kind of heist movie,” he told the Seattle Times in 1992.

Lawrence, Vicki, “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia”: Another one from “K Billy’s Super Sounds of the ’70s Weekend,” a murderous country song from 1972 brought up by Nice Guy Eddie (Chris Penn): “I thought it was the cheating wife that shot Andy!”

Laws of Gravity: In a 1993 interview with Graham Fuller, Tarantino cited Nick Gomez’s 1992 crime drama as inspiration for Reservoir Dogs’ “guerrilla-style” status.

The Lost Boys: The 1987 teen-vampire film mentioned by Mr. Orange as part of his “commode story.”

Madonna, “Like a Virgin”: Perhaps the first reflection of Tarantino’s pop-culture-addled lens comes in the opening scene of Reservoir Dogs, in which the film’s aspirant heist participants discuss the finer points of Madge’s catalogue over breakfast, centered around a theory delivered by Tarantino himself about how “Like a Virgin” is about “big dicks.”

Madonna, “True Blue”: As Nice Guy Eddie admits, “Even I’ve heard ‘True Blue.’” (Have you?)

Marvin, Lee: “I bet you’re a big Lee Marvin fan, aren’t you?” Mr. Blonde says, referencing the late actor to Mr. White as the two characters (along with Mr. Pink) endeavor to find out who botched the heist. Marvin’s oeuvre largely consisted of roles in war and Western films until his 1987 passing.

Melville, Jean-Pierre: French filmmaker whom Tarantino once cited as an influence on the costuming in Reservoir Dogs.

The Partridge Family, “Doesn’t Somebody Want to be Wanted”: The voice-over during the opening credits of Reservoir Dogs notes that this 1971 single is followed by Edison Lighthouse’s “Love Grows Where My Rosemary Goes” on — you guessed it — “K Billy’s Super Sounds of the ’70s Weekend.”

Point Blank: Tarantino described this Lee Marvin–starring neo-noir from 1967 in a 1992 interview as being “very influential” to the creation of Reservoir Dogs.

Rashomon: “It’s not exactly Rashomon, [but] you do get a sense of the characters’ different perspectives when they talk about what happened,” Tarantino told the Seattle Times about Reservoir Dogs’ different-takes-on-the-same-plot-device relation to Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 classic, which explores four contradictory viewpoints on a crime scene.

Rogers, Sandy, “Fool for Love”: The title song of Robert Altman’s Sam Shepard–starring 1985 drama, which soundtracks the scene where Mr. Orange is getting ready to leave his apartment before going on the fated heist.

The Silver Surfer: The existential oddball superhero’s poster is hanging in Mr. Orange’s apartment — try to catch it just as Mr. Orange is leaving to hop in the car with Nice Guy Eddie and the rest. (See also: the second Breathless entry.)

Stark, Richard: Tarantino described American crime writer Donald E. Westlake (Stark was one of his many pseudonyms) as influential to Reservoir Dogs.

Starsky & Hutch: Tarantino said in a 1992 interview that he wanted the Mr. Orange section of Reservoir Dogs to resemble an episode of this 1970s TV show.

Stealers Wheel, “Stuck in the Middle With You”: The 1972 lite-rock staple, co-written by Stealers Wheel’s Gerry Rafferty, which plays during the infamous torture scene.

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three: The 1974 thriller (later remade in 1998, and again in 2009) concerning a subway-hostage situation engineered by four men using color-focused code names — a trope that Reservoir Dogs is obviously indebted to.

Taxi Driver: One of a few movies Tarantino saw Keitel in as a teenager that eventually led him to cast the actor in Reservoir Dogs.

Tex, Joe, “I Gotcha”: 1972 single from the Texan soul singer that plays during the scene where the criminals start roughing up beleaguered, eventually earless police officer Marvin Nash.

The Thing: Tarantino has noted the similarities between Reservoir Dogs and John Carpenter’s 1982 masterpiece: “[I]t’s exactly the same story as my movie. A bunch of guys are trapped in one place that they can’t leave.”

Where Eagles Dare: While addressing Reservoir Dogs’ debt to The Killing in a 1992 interview, Tarantino stated, “… if I was going to make a war movie where a bunch of guys get blown up by a Nazi gun, that would be my Where Eagles Dare. If I was going to do a Western, it would be my One-Eyed Jacks … The Killing is my favorite heist film, and I was definitely influenced by it.

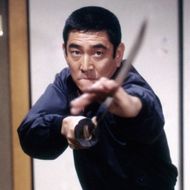

TRUE ROMANCE

Chiba, Sonny: “Bar none, the finest actor working in martial arts movies today,” or so says protagonist Clarence Worley (Christian Slater) in the film’s opening minutes while unsuccessfully trying to convince a woman at a bar to see a Chiba triple feature with him — specifically, The Street Fighter, Return of the Street Fighter, and Sister Street Fighter, all from 1974. (Tarantino would later cast Chiba in Kill Bill, too.)

The Deer Hunter: Right before the final shoot-out, Clarence compares film-producer-cum-drug-pusher Lee Donowitz’s (Saul Rubinek) Coming Home in a Body Bag to this 1978 dramatic epic by Michael Cimino.

Dr. Zhivago: This 1965 romantic epic serves as one of a few slang words for cocaine used between Clarence and Donowitz.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: One of a few films Clarence rattles off as canon to Donowitz.

Hamlet: Paraphrasing the famous quote from one of Shakespeare’s oft-referenced plays, Clarence tells Alabama Whitman (Patricia Arquette), “I knew something was rotten in Denmark,” after discovering she’s a call girl. The “rotten in Denmark” line is referenced again later in the film, by Detective Dimes (Chris Penn).

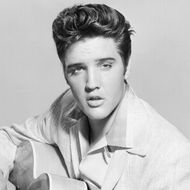

Jailhouse Rock: The Elvis-starring 1956 film referenced by Clarence in the film’s opening minutes: “He was everything rockabilly’s about … he is rockabilly. Mean, surly, nasty, rude.”

Leonard, Elmore: “I was trying to write an Elmore Leonard novel as a movie,” Tarantino said on the True Romance script in a 1993 interview with Graham Fuller, “though I’m not saying it’s as good.” (Tarantino would go on to adapt an actual Leonard novel for Jackie Brown.)

The Mack: The 1973 Richard Pryor blaxploitation film that Drexl Spivey (Gary Oldman) is watching when Clarence comes to kill him.

Mad Max: One of a few films Clarence rattles off as canon to Donowitz.

The Partridge Family: One of a few cultural references that Alabama claims was “part of the act” in meeting with Clarence.

Presley, Elvis: While Alabama dukes it out in a hotel room with Virgil (James Gandolfini), Clarence indulges his Elvis obsession by discussing a Newsweek article on the singer with a patron of a burger spot: “And then there’s the fanatics. I don’t know about you, but they give me the creeps.” At the end of the film, Alabama reveals via voice-over that she and Clarence have named their newborn son — you guessed it — Elvis.

Presley, Elvis, “Heartbreak Hotel”: Presley’s 1956 single that Val Kilmer, dressed as an Elvis impersonator, sings a cappella to Clarence.

Reynolds, Burt: Alabama’s answer for her favorite movie star when she’s first getting to know Clarence over pie at the diner.

Rio Bravo: One of a few films Clarence rattles off as canon to Donowitz.

Rourke, Mickey: One of Alabama’s listed turn-ons.

Shatner, William: Or “Bill,” as he’s referred to by a casting agent while Dick Richie (Michael Rapaport) auditions for “the new” T.J. Hooker.

Silver Bullet: In a 1993 interview with Graham Fuller, Tarantino described seeing the climax of this 1985 Stephen King adaptation as leaving a mark on him and leading to the film’s square-off between Alabama and Virgil: “I didn’t know what was going to happen.”

Spector, Phil: Alabama’s answer for what kind of music she likes (“girl-group stuff, like ‘He’s a Rebel’”).

Spider-Man No. 1: The first issue of the long-running comic book series, which Clarence shows Alabama when bringing her back to his place for the first time.

Star Trek: One of a few cultural references that Clarence says that Alabama claimed to like when they first met.

T.J. Hooker: The 1980s William Shatner–starring cop show that Dick Richie auditions for.

PULP FICTION

A Flock of Seagulls: “You — a Flock of Seagulls. You know why we’re here?” So says hitman Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson) to the impeccably coiffed couch-sitter during the film’s apartment shoot-out, a reference to the 1980s British New Wave band.

Action Jackson: One of a few films that Tarantino has compared the opening minutes of Pulp Fiction’s final third to; 1988 action flick starring Carl Weathers, Sharon Stone, and Craig T. Nelson.

Amos ’n’ Andy: A long-running radio and TV show originating in the 1920s, featuring two black characters voiced by white actors. It’s the other milkshake option provided to Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

The Aristocats: Tarantino told The Village Voice’s J. Hoberman in 1996 that he wanted Mia’s dance moves in Jack Rabbit Slim’s to be inspired by “this moment” in the 1970 Disney film “where Eva Gabor’s cat dances.”

Attack of the 50 Foot Woman: One of a few 1950s movies featured in poster form on the walls of Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Berry, Chuck, “You Never Can Tell”: This one’s easy: the song that soundtracks Mia and Vincent’s iconic dance at Jack Rabbit Slim’s. If you haven’t tried to bust one of these moves on a dance floor, you haven’t lived.

Black Mask: The 1920s pulp crime-fiction magazine that Tarantino drew inspiration from while cobbling together the film’s anthology-esque structure.

Black Sabbath: Another inspiration for the fim’s anthology-esque structure — specifically, Italian filmmaker Mario Bava’s 1963 horror-themed film.

Body and Soul: Tarantino’s cited this 1974 boxer noir as influence on Butch Coolidge’s (Bruce Willis) plotline.

“Brideless Groom”: A Three Stooges short from 1947, which drug dealer Lance (Eric Stoltz) is watching when Vincent brings the overdosed Mia to his house.

Burnette, Johnny and Dorsey, “Waitin’ in School”: Actor Gary Shorelle (impersonating Ricky Nelson) is performing this 1957 single as Mia and Vincent Vega (John Travolta) arrive at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

The Centurians, “Bullwinkle Part II”: 1963 surf-rock song that plays during (and after) Vincent’s heroin reverie and late-night drive.

Clutch Cargo: Rudimentary, semi-animated TV show from the 1960s that young Butch is watching before the infamous “watch monologue.”

Commando: One of a few films that Tarantino has compared the opening minutes of Pulp Fiction’s final third to; 1985 action thriller starring Schwarzenegger.

Cops: Moments before Vincent’s gun “accident” in the car, Vincent and Jules have a brief conversation about this long-running reality show.

Curdled: Tarantino got the idea for Winston Wolfe (Harvey Keitel), Pulp Fiction’s “cleaner,” after seeing this 1991 short at a film festival. He ended up casting Curdled’s lead actress Angela Jones in Pulp Fiction as Esmeralda Villa Lobos, and acted as producer to writer/director Reb Braddock’s full-length version of Curdled in 1996.

Dale, Dick, “Misirlou”: This surf-rock classic rips through the opening credits of the film.

Dante, Joe: Monster Joe’s Truck and Tow is a reference to Gremlins director Joe Dante.

Deliverance: Tarantino has cited the 1972 backwoods thriller as an obvious influence on the film’s infamous “gimp” sequence.

The Flintstones: Lance’s wife, Jody (Rosanna Arquette), is wearing a shirt featuring the 1960s cartoon on it when Vincent arrives at their house.

The Frames: In the sole scene she appears in, piercing enthusiast Trudi (Bronagh Gallagher) is wearing a T-shirt from this Irish rock band.

Gerron, Peggy Sue: The titular subject of Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue” — as well as what the waiter at Jack Rabbit Slim’s calls Mia.

Godard, Jean-Luc: One of Tarantino’s favorite film directors. He named his production company A Band Apart after the French New Wave iconoclast 1963 film Bande à Part, and he also claims on the Pulp Fiction DVD’s special features that Godard’s work inspired that film’s iconic dance scene between Mia and Vincent: “My favorite musical sequences have always been in Godard because they just come out of nowhere. It’s so infectious, so friendly. And the fact that it’s not a musical but he’s stopping the movie to have a musical sequence makes it all the more sweet.”

Green Acres: 1960s sitcom referenced in the film’s final section, during a conversation between Vincent and Jules.

Green, Al, “Let’s Stay Together”: The song that plays during the fixed-fight conversation between Butch and Marcellus Wallace (Ving Rhames).

The Green Lantern: In a 1994 interview, Tarantino compared Jules’ Bible quote he recites before killing someone as similar to what this comic book character typically does, “saying his little speech.”

The Guns of Navarone: Or, as Jules incorrectly refers to the 1961 Western, “The Guns of the Navarone,” during a heated conversation with Vincent.

Gunsmoke: Winston Wolfe’s utterance to “get the hell out of Dodge” is a famous catchphrase associated with this long-running Western TV show.

Happy Days: Jules references Fonzie from the 1970s/’80s retro-fixated sitcom during the final moments of the film.

His Girl Friday: The first page of Pulp Fiction’s script describes Pumpkin and Honey Bunny as conversing in “rapid-fire motion,” à la this 1940 Howard Hawks classic.

Holly, Buddy: Mia and Vincent’s waiter at Jack Rabbit Slim’s is dressed to ape the mannerisms of the late singer.

Joe Palooka: 1930s comic-strip-cum-multimedia-franchise (radio series! feature films! board games! wristwatches!) referenced by Vincent when he refers to Butch as “Palooka.”

Karate Kiba (The Bodyguard): 1976 Sonny Chiba film that was the source for the mostly fabricated Bible quote (specifically, Ezekiel 25:17) that Jules recites several times throughout the film.

Kirby, Durward: The host of 1950s TV shows The Garry Moore Show and Candid Camera, as well as the name of the burger Mia orders at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Kiss Me Deadly: 1955 noir in which the lead, Ralph Meeker, served as inspiration for Butch as a character: “I wanted him to be basically like Ralph Meeker as Mike Hammer in Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly. I wanted him to be a bully and a jerk.” (Like Pulp Fiction, Kiss Me Deadly also featured a glowing briefcase.)

Kool & the Gang, “Jungle Boogie”: The 1973 song playing on the radio in Pulp Fiction’s first scene featuring Vincent and Jules.

Kung Fu: When Jules describes his desire to “walk the earth,” he references the character Caine from this 1970s TV show.

LaRue, Lash: Western actor from the 1940s/’50s referenced in conversation between Winston and Vincent.

The Lively Ones, “Surf Rider”: The song that closes out the film.

Madonna, “Lucky Star”: “I have a bit of a tummy, like Madonna did when she did ‘Lucky Star,’” Butch’s girlfriend, Fabienne (Maria de Medeiros), says to him in Pulp Fiction.

Mansfield, Jayne: Mia mistakes the Jack Rabbit Slim’s waitress portraying the late actress for the waitress portraying Marilyn Monroe.

Martin and Lewis: Or the performance duo of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, which is also one of the milkshake options at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Modesty Blaise: The 1965 spy novel from British writer Peter O’Donnell, which Vincent is seen holding several times during the film.

Monroe, Marilyn: “We should’ve sat in Marilyn Monroe’s section,” Vincent says to Mia while they dine at Jack Rabbit Slim’s. “I don’t think Buddy’s that much of a waiter.”

Motorcycle Gang: One of a few 1950s movies featured in poster form on the walls of Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Nam’s Angels: Jack Starrett’s 1970 biker-gang film is the movie that Fabienne is watching in the hotel where she hides out with Butch.

Nelson, Ricky, “Lonesome Town”: 1958 recording of the Baker Knight–written song that plays while Mia and Vincent attend Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Ray, Aldo: Tarantino claims in a 1994 interview with Manohla Dargis that Bruce Willis reminds him of this American tough-guy actor’s look in Jacques Tourneur’s 1957 film Nightfall. (Brad Pitt’s Aldo Raine character in Inglorious Basterds is an ostensible homage to the actor, too.)

The Revels, “Comanche”: The 1961 surf-rock song that soundtracks the infamous “gimp” sequence.

The Robins, “Since I First Met You”: 1957 single that soundtracks Mia and Vincent’s conversation regarding what really happened to Tony Rocky Horror.

Rock All Night: One of a few 1950s movies featured in poster form on the walls of Jack Rabbit Slim’s (as well as one of the films that inspired Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez to make Grindhouse).

Salinger, J.D.: In a 1994 interview, Tarantino cited the reclusive author’s Glass family stories as influential to the film: “They’re all building up to one story, characters floating in and out.”

Silver, Joel: Tarantino has compared selected works from this action-blockbuster producer to the opening minutes of Pulp Fiction’s final third.

Sirk, Douglas: The steak that Vincent orders — “bloody as hell,” of course — at Jack Rabbit Slim’s is named after the film director and master of melodrama.

Sorority Girl: One of a few 1950s movies featured in poster form on the walls of Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Steppenwolf, “The Pusher”: Mia references a lyric from this 1969 song (that appeared in Easy Rider, no less) after snorting some coke in the bathroom of Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Super Fly T.N.T.: One of the films Jules cites to Vincent during a heated conversation.

Springfield, Dusty, “Son of a Preacher Man”: Mia throws this song on when Vincent first enters the Wallace household.

Statler Brothers, “Flowers on the Wall”: The 1965 single’s on the radio when Butch runs into Marcellus with his car.

Takakura, Ken: Tarantino’s screenplay states that Butch holds his notorious samurai sword in the “style” of this Japanese actor.

Thorne, Woody, “Teenagers in Love”: 1961 single that soundtracks Mia and Vincent’s conversation regarding what really happened to Tony Rocky Horror.

The Tornadoes, “Bustin’ Surfboards”: Another surf-rock classic that pops up on Pulp Fiction’s soundtrack — this one surfaces during the body-piercing discussion in the film’s first third.

Unforgiven: Jules tells Vincent that Winston is “about as European as English Bob,” an assumed reference to a character in Clint Eastwood’s 1992 neo-Western.

Urge Overkill, “Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon”: The deadpan rock act’s cover of the Neil Diamond fromage-classic was one of a thousand pop-cultural artifacts lifted to prominence after appearing in Pulp Fiction.

Van Doren, Mamie: “She must’ve had the night off,” Vincent remarks in Jack Rabbit Slim’s while correcting Mia’s confusion of which restaurant waitress is portraying Marilyn Monroe.

Willeford, Charles: In conversation with Manohla Dargis in 1994, Tarantino described a kinship between Pulp Fiction and the work of this hard-boiled American writer.

Wray, Link, “Ace of Spades”: One of two songs from the guitar-rock pioneer played during Mia and Vincent’s Fox Force Five–five-dollar-shake conversation.

Wray, Link, “Rumble”: One of two songs from the guitar-rock pioneer played during Mia and Vincent’s Fox Force Five–five-dollar-shake conversation.

The Young Racers: One of a few 1950s/’60s movies featured in poster form on the walls of Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Zardoz: Sean Connery’s character from John Boorman’s 1974 gonzo sci-fi blowout shares a name with Zed, the pawnshop security guard in the film’s “gimp” sequence.

FOUR ROOMS (“THE MAN FROM HOLLYWOOD”)

Beat the Clock: 1950s TV game-show referenced as Chester Rush (played by Tarantino himself) lightly chides in conversation with the film’s bellboy, Ted (Tim Roth).

The Bellboy: 1960 Jerry Lewis film that Hollywood bigwig Chester expresses enthusiasm for in conversation with Ted.

Glengarry Glen Ross: “Always! Be! Closing!” Chester shouts near the segment’s end, quoting the classic David Mamet play/film.

“Man From the South”: A Roald Dahl short story that was adapted into an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents in 1960, starring Peter Lorre and Steve McQueen; it serves as the basis for Tarantino’s contribution to Four Rooms, “The Man From Hollywood.” In an uncredited role, Bruce Willis incorrectly refers to this story as The Man From Rio.

Quadrophenia: When Chester’s friend Norman shouts, “Bellboy!” Chester notes that Norman is quoting Franc Roddam’s 1979 film adaptation of the Who’s rock opera.

FROM DUSK TILL DAWN

Cushing, Peter: British actor famed for playing vampire killer Dr. Van Helsing in several films in the 1950s and ’60s. Cushing is referenced as the survivors of the initial Titty Twister bloodbath examine their options among vampire-killing crosses.

Fuller, Samuel: Legendary pulp filmmaker whose influence inarguably looms over Tarantino’s entire career. The family held captive throughout From Dusk Till Dawn share a last name with the director in obvious homage.

The Getaway: The 1958 crime novel from Jim Thompson, which was later adapted into two separate films, was an influence on Tarantino’s screenplay.

Satanico Pandemonium: The name itself of Santanico Pandemonium (Salma Hayek) is inspired by this 1975 Spanish satanic-panic-plus-nuns film directed by Gilberto Martínez Solares.

That Darn Cat! Criminal Seth Gecko’s (George Clooney) quote, “I’ve got six little friends and they can all run faster than you can,” is a direct lift from this kooky 1965 feline caper.

The Wild Bunch: “I will turn this place into the fucking Wild Bunch,” Seth utters in the opening moments of the film, referencing the ultraviolent 1969 Western classic. Another reference takes when Kate Fuller (Juliette Lewis) asks, “What’s in Mexico?” and Richie Gecko (Tarantino) replies, “Mexicans” — that exact exchange also appears in The Wild Bunch.

JACKIE BROWN

Ayers, Roy: The legendary jazz artist’s work (specifically for the soundtrack to the 1973 Pam Grier film Coffy) can be found all over Jackie Brown.

Bishop, Elvin, “She Puts Me in the Mood”: Song that plays while Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson) is on the phone with Louis Gara (Robert De Niro) in the film’s final third.

Bloodstone, “Natural High”: Buttery 1973 single that plays the first time Max Cherry (Robert Forster) meets Jackie (Pam Grier).

The Brothers Johnson, “Strawberry Letter 23”: Shuggie Otis–penned 1977 single that makes an appearance early in the film.

Cash, Johnny, “Tennessee Stud”: Cut from Cash’s 1994 album American Recordings that plays as Ordell waits outside Jackie’s house.

Crawford, Randy, “Street Life”: 1979 soul single that plays while Jackie’s on her way to the mall in the film’s final third.

The Delfonics: This Philadelphia soul outfit is featured several times during Jackie Brown — specifically the singles “Didn’t I Blow Your Mind This Time” and “La La La Means I Love You.”

Dirty Mary Crazy Larry: 1974 action caper that Melanie Ralston (Bridget Fonda) is seen watching during a scene — and starring the actress’s father, Peter, no less.

Foxy Brown: Even the text of the original Jackie Brown poster is a reference to the 1974 blaxploitation classic Foxy Brown.

Foxy Brown, “(Holy Matrimony) Letter to the Firm”: The rapper this time. This cut from Brown’s 1996 album Ill Na Na plays while Max goes shopping for a Delfonics tape.

The Graduate: The opening of Jackie Brown is an obvious homage to the opening credits of this classic 1967 Mike Nichols dramedy.

The Grass Roots, “Midnight Confessions”: 1968 psych-pop song that plays right after Louis kills Melanie in the mall’s parking lot.

The Guess Who, “Undun”: 1969 single from the Canadian rockers that plays while Melanie and Louis are getting ready in the film’s final third.

Haig, Sid: This blaxploitation-era actor appears in the film as the judge that hands Jackie her prison sentence — and his name also appears as an Easter egg on the tenant list at Jackie’s apartment building.

Hauer, Rutger: Ordell incorrectly identifies La Belva col Mitra star Helmut Berger as this Dutch actor while Melanie watches the movie on the couch.

Hill, Jack: Along with Sid Haig, this blaxploitation-era director’s name is hidden on the tenant list in Jackie’s apartment building.

Jackson, Jermaine, “My Touch of Madness”: 1976 single playing when Max and Jackie get a drink at a bar.

The Killer: Classic 1989 John Woo actioner referenced by Ordell when he explains that people typically want to buy two guns rather than one “because they all wanna be the killer.”

La Belva col Mitra: 1977 Italian crime film that Melanie watches on TV.

The Vampire Sound Corporation, “The Lions and the Cucumber”: This groovy instrumental is taken from the 1971 erotic horror film Vampyros Lesbos — and it plays when Max and Ordell talk on the phone during the film’s final moments.

The Meters, “Cissy Strut”: The 1969 song from the New Orleans funk wrecking crew that was playing when we first meet Max.

Orchestra Hollow, “Grazing in the Grass”: 1968 Hugh Masekela single (rerecorded here by Larry Harlow’s Orchestra Harlow) playing when Ordell kills Louis.

Riperton, Minnie, “Inside My Love”: 1975 single that plays during a conversation between Jackie and Ordell.

Rum Punch: The 1992 Elmore Leonard novel that Jackie Brown is based on.

Slash’s Snakepit, “Jizz da Pitt”: This unbelievably obscure cut from former Guns N’ Roses guitarist Slash’s other band soundtracks the “Chicks Who Love Guns” video that Louis and Ordell are watching in the beginning of the film.

Straight Time: 1978 Dustin Hoffman–starring Ulu Grosbard crime drama that, according to a 1998 interview, inspired the film’s “down-to-earth” look.

The Supremes, “Baby Love”: Simone (Hattie Winston) sings along to this 1964 Motown classic to Louis.

The Switch: 1978 Elmore Leonard book featuring characters from Jackie Brown, as well as the first Leonard book that Tarantino had ever read.

Withers, Bill, “Who Is He (and What Is He to You?)”: Song from Withers’ 1972 album Still Bill that plays during a conversation between Louis and Ordell.

Womack, Bobby, “Across 110th Street”: The late singer’s classic song plays over the (pretty much perfectly framed) opening credits of Jackie Brown.

KILL BILL VOLs. 1 & 2

The 5.6.7.8’s: This real-life Japanese retro-rock trio performs as Beatrix Kiddo (Uma Thurman) enters the House of Blue Leaves in Vol. 1.

Archie Bell & the Drells: R&B group and one of the artists that Rufus (Samuel L. Jackson) claims he used to play for in Vol. 2.

The Bar-Kays: Funk group and one of the artists that Rufus claims he used to play for in Vol. 2.

Bell, Jeannie: Vernita Green’s (Vivica A. Fox) alias, Jean Bell, is a reference to this 1970s actress (Mean Streets, T.N.T. Jackson).

Betts, Harry, “Police Check Point”: Betts’s musical cue from the 1973 Pam Grier film Black Mama White Mama is one of a few songs interspersed through Vol. 1’s House of Blue Leaves sequence.

Black Lizard: 1968 Kinji Fukasaku detective film from which Tarantino drew the idea for Vol. 1’s Crazy 88s gang.

Black Sunday: This 1977 John Frankenheimer film — specifically, a scene where Marthe Keller attempts to poison Robert Shaw by disguising herself as a nurse — served as an influence for the scene where Elle Driver (Daryl Hannah) disguises herself as a nurse and tries to kill Beatrix with a syringe.

The Blood Spattered Bride: The second chapter of Vol. 1 — specifically, “The Blood Splattered Bride” — references this 1974 Vicente Aranda thriller.

Cash, Johnny, “A Satisfied Mind”: Cash’s version of this country standard plays in Budd’s (Michael Madsen) trailer before his first confrontation with Beatrix in Vol. 2.

Champions of Death: Shuzsuko Kibushi’s title theme to this 1975 Sonny Chiba film plays during the House of Blue Leaves sequence in Vol. 1.

Brown, Charlie: Members of the Crazy 88s compare an employee at the House of Blue Leaves to this Peanuts character while demanding “four pepperoni pizzas” in Vol. 1.

The Chinese Boxer: 1970 Jimmy Wang Yu film with a massive fight scene that served as inspiration for Vol. 1’s House of Blue Leaves sequence.

Chingón, “Malagueña Salerosa”: Robert Rodriguez’s band Chingón performs this Mexican traditional over the end credits of Vol. 2.

Circle of Iron: David Carradine — the titular Bill — starred in this 1978 martial-arts film. The bamboo flute that he personally carved for that film also makes a cameo in Kill Bill.

The Coasters: Doo-wop group, and one of the artists that Rufus claims he used to play for in Vol. 2.

Day of Anger: Riz Ortolani’s main theme to this 1967 spaghetti Western zips right by the audience as Beatrix plucks the eye out of an unfortunate Crazy 88s member in Vol. 1. (This theme also surfaces in Django Unchained.)

Death Rides a Horse: “The bandits who killed five defenseless people made one big mistake. They should’ve killed six.” So goes the trailer for this 1969 spaghetti Western. Similarly, Beatrix utters at one point in the film, “The DiVAS thought they killed ten people that day, but they made a mistake — they only killed nine.” (Morricone’s main theme plays when Beatrix first confronts O-Ren during Vol. 1, too.)

The Doll Squad: Low-budget 1973 action film that influenced the look of the DiVAS.

The Drifters: R&B group and one of the artists that Rufus claims he used to play for in Vol. 2.

Feathers, Charlie, “Can’t Hardly Stand It”: 1956 rockabilly single that plays when Beatrix wakes up after being shot by Budd in Vol. 2.

Feathers, Charlie, “That Certain Female”: 1974 rockabilly single that plays over the opening of “The Blood Splattered Bride” sequence in Vol. 1.

Female Convict Scorpion: The Meiko Kaji–sung theme to this 1970s revenge film series (the first of which also stars Kaji) plays over the closing credits of both films.

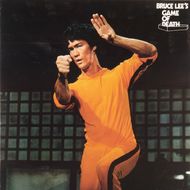

Game of Death: Bruce Lee’s iconic tracksuit donned in this 1972 chop-em’-up classic — written, directed, and starring Lee, it was the actor’s last film before he passed away in the middle of shooting — is replicated to similar effect by Beatrix in the House of Blue Leaves scene in Vol. 1.

Goke, Body Snatcher From Hell: The opening scenes from this 1968 Japanese sci-fi film were a visual influence for the orange sunset hues filtered through the airplane windows in Vol. 1.

The Grand Duel: The title theme from this 1972 Western plays during Vol. 1’s anime sequence.

The Green Hornet: The theme song to this short-lived 1960s crimefighter TV series, performed by late trumpeter Al Hirt, plays during Vol. 1 as Beatrix travels to the House of Blue Leaves.

Hannie Caulder: British Western from 1971 that Tarantino claimed was an influence on Kill Bill in a 2003 interview: “[T]here’s a bit of similarity between Sonny Chiba and Uma and Raquel Welch and Robert Culp [in Hannie Caulder].”

Honey West: One-season ABC sitcom (1965–66, specifically) that also served as an influence on the look of the DiVAS.

Hotei, Tomoyasu: Japanese guitarist whose instrumental work is featured throughout Kill Bill.

The Human Beinz, “Nobody But Me”: 1967 cover of the Isley Brothers song from this garage-rock outfit; plays during the House of Blue Leaves sequence in Vol. 1.

Ichi the Killer: Typically violent Takashi Miike film from 2001 that Tarantino claimed in a 2003 interview was an influence on the Kill Bill films.

Ironside: The Quincy Jones theme song from this 1960s/’70s NBC cop drama (not the recent failed remake) is used liberally whenever Beatrix sees an enemy throughout Kill Bill.

Ishii, Katsuhito: Japanese film director and friend of Tarantino’s who contributed animation to the anime section of Vol. 1.

Jackass: The Movie: Yes, Jackass: Tarantino said in a 2003 interview that seeing the first installment of Johnny Knoxville’s film endeavors with the Jackass clan influenced the the “gross” elements of the battle between Elle and Beatrix in Vol. 2.

Kage no Gundan: Translated to Shadow Warriors in Japanese, this 1980s TV show, which Tarantino watched during its original airing, featured a character named O-Ren, which inspired the name of O-Ren Ishii (Lucy Liu). Oh, yeah — and Chiba’s Hattori Hanzo character on Kage no Gundan is reprised by Chiba himself in Kill Bill, too.

Kool & the Gang: Funk group and one of the artists that Rufus claims he used to play for in Vol. 2.

Kuriyama, Chiaki: The actress who plays Gogo Yubari also starred in the 2000 cult classic Battle Royale, a personal favorite of Tarantino’s.

Lady Snowblood: 1973 Japanese revenge film that Tarantino has cited as influence on Kill Bill; the closing theme from the film, “The Flower of Carnage,” appears in the film as well.

Lily Chou-Chou, “Kaifuku Suru Kizu”: 1999 single from this defunct Japanese band acting as an avatar for a fictional character; plays during the scene where Beatrix acquires a Hattori Hanzo sword in Vol. 1.

Lole y Manuel, “Tu Mira”: 1975 song from this flamenco duo that plays as Beatrix heads toward her final fight in Vol. 2.

Long Days of Vengeance: Music composed for this 1967 spaghetti Western by composer Armando Trovajoli plays during Kill Bill’s anime sequence.

McLaren, Malcolm, “About Her”: The legendary provocateur’s obscure Zombies sorta-cover (once the focus of a plagiarism case) plays as Beatrix puts B.B. to bed after watching Shogun Assassin in Vol. 2.

Master of the Flying Guillotine: Music from the soundtrack from this 1976 Taiwanese action film — specifically, German experimental band Neu!’s “Super 16” — was used as cues for Kill Bill.

Master Killer: Also known as The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, the 1978 Shaw Brothers film starring Gordon Liu; Tarantino is a “big fan” of the film and cast Liu in Kill Bill, too.

Presley, Elvis, “Love Me Tender”: 1956 single that Rufus, the church organist, offers to play during Beatrix’s wedding in Vol. 2.

The Psychic: The theme from this 1977 Lucio Fulci horror film, “Seven Notes in Black,” appears in Kill Bill.

Road to Salina: Music from the score to this 1970 thriller is included in the first third of Vol. 2.

The RZA: Wu-Tang Clan’s main man, who contributed original music to Kill Bill’s soundtrack.

Santa Esmeralda, “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”: 1977 cover of the Nina Simone classic from French disco band that plays during the final battle between Beatrix and O-Ren Ishii in Vol. 1.

The Shaw Brothers: Runje, Runme, and Runde, specifically: the brothers who ran the largest film production company in Hong Kong from 1958 to 2011. Their logo appears with great fanfare before the beginning of Vol. 1.

Shogun Assassin: 1980 samurai film that Beatrix and B.B. watch together in the final scenes of Vol. 2.

Sinatra, Nancy, “Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)”: Classic 1966 single that plays over the opening credits of Vol. 1.

The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh: An excerpt of Nora Orlandi’s score from this 1971 giallo plays during a conversation between Bill and Budd in Vol. 2.

The Summertime Killer: The theme from this 1972 Spanish crime film plays as Beatrix enters Bill’s house for the first time in Vol. 2.

They Call Her One Eye: Swedish exploitation film from 1974 that served as inspiration for Kill Bill’s one-eyed (get it?) Elle Driver character. Tarantino had Daryl Hannah watch the film as prep as well.

Thomas, Rufus: Late soul singer and one of the artists that Rufus claims he used to play for in Vol. 2.

Three Tough Guys: Isaac Hayes’ score for this 1974 crime drama surfaces during the anime sequence in Vol. 1.

Truck Turner: Isaac Hayes’ opening theme from this Hayes-starring 1974 film plays when Beatrix finds the Pussy Wagon in the hospital parking lot.

Twisted Nerve: Elle Driver whistles Bernard Herrmann’s theme from this 1968 thriller while walking through the hospital in her attempt to kill Beatrix. (It’s also Abernathy Ross’s [Rosario Dawson] ringtone in Death Proof.)

War of the Gargantuas: 1966 Ishiro Honda monster film that served as inspiration for the miniature set of Tokyo shot specifically for the film; during the film’s genesis, Tarantino specifically screened Gargantuas for Daryl Hannah as well.

White Lightning: Charles Bernstein’s score for this 1973 Burt Reynolds vehicle plays during the House of Blue Leaves sequence in Vol. 1 (Tarantino later used it for Inglourious Basterds, too).

Yagyu Conspiracy: The speech that Beatrix gives near the end of Vol. 1 is a paraphrasing from a speech that Chiba would repeat at the beginning of every episode of this short-lived Japanese TV series from the ’70s.

Zamfir, Gheorghe, “The Lonely Shepherd”: The pan-flute virtuoso’s take on the James Last theme plays over the closing credits of Vol. 1.

DEATH PROOF

AMI: Pronounced Amy, the jukebox in the Texas Chili Parlor is loaded with songs that Tarantino specifically selected himself — it’s a very long list. Check it out here.

April March, “Chick Habit”: This 1995 Serge Gainsbourg cover plays during the film’s closing credits.

B.J. and the Bear: Dov (Eli Roth) references this short-lived action sitcom while drawing attention to Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell) early in the film.

Bullitt: One of the license plates on Stuntman Mike’s cars is a reference to an identical license plate from this 1968 Steve McQueen classic.

Cage, Nicolas: During Death Proof’s Tennessee section, Kim Mathis (Tracie Thoms) claims that the film the women are working on has someone on set who looks like this actor.

Cannonball Run: 1981 Burt Reynolds caper classic that’s referenced by Jungle Julia after Butterfly’s lap dance.

The Coasters, “Down in Mexico”: Leiber & Stoller–written 1956 single that plays during Butterfly’s lap-dance scene.

Convoy: The “rubber duck” hood ornament featured on this 1978 Sam Peckinpah film sits on the hood of Stuntman Mike’s cars.

Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick, & Tich, “Hold Tight”: Jungle Julia calls up the radio station to request this 1966 British rock single.

Deville, Willy, “It’s So Easy”: Jack Nitzsche–produced 1980 single recorded for the soundtrack for the William Friedkin film Cruising; it plays in the beginning of Death Proof’s Tennessee section.

Dragstrip Girl: Along with Rock All Night (a poster of which made a cameo on the wall of Jack Rabbit Slim’s in Pulp Fiction), this 1957 film inspired Grindhouse’s double-feature setup after Rodriguez saw the double-feature poster of this and Rock All Night on Tarantino’s wall in his house.

El Limite Del Amor: A poster for this 1976 film can be found on the wall of the bar featured in the film’s opening minutes.

En Carne Viva: A poster for this 1951 Mexican film can be found on the wall of the bar featured in the film’s opening minutes.

Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! Shanna’s (Jordan Ladd) T-shirt is emblazoned with late actress Tura Satana’s character from this 1965 Russ Meyer cult film.

Floyd, Eddie, “Good Love Bad Love”: 1966 single that plays at the Texas Chili Parlor.

Gavilan: The 1980s TV spy-show that Stuntman Mike claims he worked on as a stunt double for Robert Urich.

Gone in 60 Seconds: Kim cites the 1974 original (“Not that Angelina Jolie shit”) as one of the films she watched as a child during the film’s Tennessee section.

Hannah, Daryl: Abernathy Ross (Rosario Dawson) claims that a romantic interest “fucked” this actress’s stand-in during Death Proof’s Tennessee section.

Herman, Pee-wee: During Death Proof’s Tennessee section, Kim claims that the film the women are working on has someone on set who looks like Paul Reubens’s iconic character.

The High Chaparral: 1960s TV Western that Stuntman Mike claims he once starred in an episode of.

High Crime: Music from this 1973 Italian crime drama plays during the film’s final chase scene.

Johnson, Dwayne: Or “the Rock” — which he’s referred to as Lee Montgomery (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) describes a romantic interest who looks like the wrestler-cum-actor.

Junior Bonner: In an early scene, Marcy (Marcy Harriell) is wearing a T-shirt referencing the Italian title of this 1972 Sam Peckinpah film.

La Mujer sin Lágrimas: The poster for this 1951 film is one of a few hanging on the wall of the bar featured in the film’s opening minutes.

Las Tres Elenas: A poster for this 1954 film can be found on the wall of the bar featured in the film’s opening minutes.

Lohan, Lindsay: Abernathy is “doing” this actress’s makeup on the film that the girls in the film’s Tennessee section are working on.

Nitzsche, Jack, “The Last Race”: This single from the late musical journeyman served as the main theme for 1965’s Village of the Giants, as well as the music that plays over the opening credits here.

Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film: 1992 book by film theorist Carol Clover, which Tarantino claimed in a 2008 interview with Sight & Sound served as “one of the biggest inspirations” for Death Proof.

Pacific Gas and Electric, “Staggolee”: One of the songs playing at the Texas Chili Parlor early in the film.

Paranoia: A poster for this 1970 giallo can be found on the wall of Jungle Julia’s apartment.

Pretty in Pink: “Y’all grew up watching that Pretty in Pink shit,” Kim says to the rest of the girls in the diner scene during the film’s Tennessee section.

Smith, “Baby It’s You”: This 1969 cover of the Burt Bacharach–penned Shirelles tune appears in the first third of Death Proof; Lee sings the song during the film’s Tennessee section, too.

Soldier Blue: A poster for this 1970 Western can be found on the wall of Jungle Julia’s apartment.

A Special Cop in Action: Music from this 1976 Italian crime drama plays during the film’s final chase scene.

Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure: A foreign-language poster for this 1959 film can be found on the wall of the bar featured in the film’s opening minutes.

Tex, Joe, “The Love You Save (May Be Your Own)”: 1966 single that plays at the Texas Chili Parlor early in the film.

Thunder Alley: Eddie Beram’s “Riot in Thunder Alley” is featured in this 1967 racing film, as well as the scene where Stuntman Mike goes after the woman in the film’s Tennessee section.

The Women: Tarantino’s said that Death Proof is his version of this 1939 George Cukor comedy, which was remade quite disastrously in 2008.

Vanishing Point: Real-life stuntwoman Zoe Bell (playing herself, natch) and her friends commandeer a 1970 Dodge Challenger similar to the one driven in the 1971 existential stoner-action cult classic Vanishing Point. Bell refers to the film as “one of the best American films ever made.”

Vega$: The 1970s Michael Mann–created TV series that Stuntman Mike claims he did car stunts on for actor Robert Urich.

The Virginian: The 1960s TV Western on which Stuntman Mike claims he worked on “a couple of” episodes, as actor Gary Clarke’s stunt double. “They brought on Lee Majors, and then I doubled him.” (Kurt Russell appeared on the show as a child in real life.)

What Have They Done to Your Daughters? Music from this 1974 Italian crime-drama plays during the film’s final chase scene.

White Line Fever: 1975 truck-driver actioner referenced by Stuntman Mike while he explains how, exactly, his car is “death-proof.”

Zatoichi: Jungle Julia refers to Stuntman Mike as this blind Japanese samurai character (who was the focus of 26 films between 1962 and 1989) the first time the two characters meet.

INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS

Bela B.: The drummer of German band Die Ärzte has a cameo in the film as a cinema usher.

Beyond the Law: Musical cues from Riz Ortolani’s score for this 1968 spaghetti Western play during the third chapter of the film.

Bowie, David, “Cat People”: Perhaps the quirkiest musical cue to appear in the film, Bowie’s 1982 single plays as preparations for the film’s final third are made by its characters.

Clouzot, Henri-Georges: When the Germans come to bring Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent) to meet with Joseph Goebbels (Sylvester Groth), the former is putting this French director’s name up on her theatre’s marquee.

Confessions of a Nazi Spy: 1939 Anatole Litvak film that Tarantino’s cited as one of his “Hollywood propaganda movie” influences in making Inglourious Basterds.

Davie Allan & the Arrows, “The Devil’s Rumble”: ’60s surf-rock cut that plays during the final third of the film.

Dark of the Sun: Music from Jacques Loussier’s score for this 1968 war film makes a few appearances throughout the film.

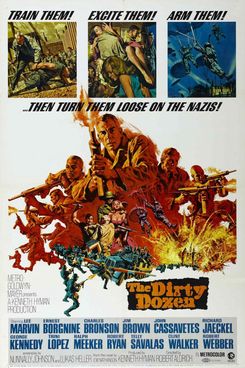

The Dirty Dozen: Tarantino told Fresh Air host Terry Gross in 2009 that Basterds bears relation to Robert Aldrich’s classic war film from 1967.

The Entity: Charles Bernstein’s “Bath Attack,” for the score to this 1982 thriller, plays when Shosanna meets Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) for the first time since he killed her family years previous.

Glückskinder: The 1936 film screened for Goebbels and the others at Shosanna’s cinema.

The Inglorious Bastards: Obvious, yes — but not as obvious as you’d think: Tarantino bought the title to the 1978 Enzo G. Castellari action film for Inglourious Basterds, but very little of the original’s plot appeared in Tarantino’s film.

Katzenjammer Kids: Long-running comic strip referenced in conversation between Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender) and Ed Fenech (Mike Myers).

Kelly’s Heroes: Lalo Schifrin’s “Tiger Tank,” from this 1970 war film, plays right before the film’s explosive climax.

The Kid: The 1921 Charlie Chaplin film that Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Brühl) tells Shosanna Dreyfus “[Max] Linder never made a film as good” as.

King Kong: The racial subtexts of the 1933 film are discussed during a scene in the film.

Linder, Max: Silent-era film star whom Shosanna’s theatre is running a festival on.

Man Hunt: 1941 Fritz Lang film that Tarantino’s cited as one of his “Hollywood propaganda movie” influences in making Inglourious Basterds.

Mrs. Miniver: In a 2009 interview with Sight & Sound, Tarantino compared Bridget (Diane Kruger) to Greer Garson’s character in this 1942 war drama.

One Silver Dollar: Gianni Ferrio’s theme from this 1965 spaghetti Western plays during the third chapter of the film. Broomhilda’s dress in the final scene of Django Unchained was also inspired by the dress worn by Ida Galli in this film.

Rare Earth, “What’d I Say”: Reunion in France: 1942 Jules Dassin film that Tarantino’s cited as one of his “Hollywood propaganda movie” influences in making Inglourious Basterds.

Sabotage: A clip from this 1936 Alfred Hitchcock film is shown to explain the flammability of nitrate film.

Selznick, David O.: Legendary film producer (Gone With the Wind) referenced in conversation between Archie Hicox and Ed Fenech.

Slaughter: The Billy Preston–penned theme to this 1972 blaxploitation film plays during the scene where Hugo Stiglitz (Til Schweiger) is introduced.

Stiglitz, Hugo: Tarantino paid clever tribute to this Mexican actor by naming Schweiger’s character in the film after him.

This Land Is Mine: 1943 Jean Renoir film that Tarantino’s cited as one of his “Hollywood propaganda movie” influences in making Inglourious Basterds.

Tiomkin, Dimitri, “The Green Leaves of Summer”: Composer Nick Perito’s version of this Oscar-nominated song written for 1960’s The Alamo plays during the opening credits of the film.

The White Hell of Pitz Palu: 1929 Leni Riefenstahl–starring German silent film that’s on the marquee the first time we see the movie theatre.

Zulu Dawn: Elmer Bernstein’s “Zulus,” from the score for this 1979 war film, plays right before the film’s explosive climax.

DJANGO UNCHAINED

Bacalov, Luis, “Django”: The theme song from the original Django that plays over the film’s opening credits. (Various excerpts from Bacalov’s catalogue are scattered throughout the film’s score, too.)

Beethoven, “Für Elise”: The pianist in Calvin Candy’s (Leonardo DiCaprio) drawing room plays this classical standard — that is, until Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) tells her to cut it out.

The Birth of a Nation: D.W. Griffith’s infamous epic served as inspiration for the Klansmen scene in this film.

The Blue Boy: Django’s valet getup was inspired by Thomas Gainsborough’s 1770 painting.

Bonanza: Costume designer Sharen Davis told Vanity Fair that Django’s wardrobe was inspired by this long-running TV Western.

Brown, James, “The Payback”: This classic James Brown cut is mashed up with Tupac’s “Untouchable” during the film’s shoot-out climax.

Cash, Johnny, “Ain’t No Grave”: A “Black Opium” remix of this song plays during the film’s final third.

Croce, Jim, “I’ve Got a Name”: Classic AM-dial staple that plays during Django (Jamie Foxx) and Dr. King Schultz’s traveling-toward-Candyland journey.

Django: 1966 Franco Nero–starring spaghetti Western that Tarantino paid tribute to by giving Nero a brief cameo in Django Unchained.

Drum: This 1976 film is a sequel to the previous year’s Mandingo. Besides featuring future Jackie Brown star Pam Grier, its plot set in the Antebellum South served as inspiration for Django Unchained.

Dumas, Alexandre: The Three Musketeers author, whom Dr. King Schultz references in his final speech.

Gone With the Wind: Calvin Candy’s costume was partially inspired by Rhett Butler’s own getup in this classic film.

The Great Silence: This 1968 spaghetti Western served as inspiration for the scenes where Django and Dr. King Schultz travel through the snow.

Havens, Richie, “Freedom”: Song that plays when Django gives up after the initial firefight in the film’s final third.

Kojak: Dr. King Schultz’s opulent coat was inspired by Telly Savalas’s getup from this 1970s cop TV show.

Mandingo: Tarantino’s said he drew inspiration from this 1976 film (the prequel to Drum) for Django Unchained’s “Mandingo fighting” sequence.

Miami Vice: Don Johnson, the star of the original 1980s TV show, briefly resurfaced in Django Unchained as Big Daddy — and his costume as the plantation owner was inspired by the cream-whites of Johnson’s iconic Miami Vice getup.

They Call Me Trinity: Part of Franco Micalizzi’s musical contribution to this 1970 Western plays near the end of the film.

Under Fire: Jerry Goldsmith and Pat Metheny’s “Nicaragua,” which was contributed to this 1983 Nick Nolte war drama, appears as part of the score for Django Unchained.

The White Buffalo: Charles Bronson’s sunglasses in this 1977 Western inspired the sunglasses that Django wears in the film.