If Steve Orlando has his way, a new term is about to enter the pop-culture lexicon: queersploitation. That’s the word the up-and-coming comics writer has used to describe Virgil, his thrilling new graphic-novel collaboration with artist J.D. Faith for Image Comics. It follows a gay policeman in Kingston, Jamaica, as he seeks revenge against the bigoted and corrupt cops who brutalized him and kidnapped his boyfriend. It’s a fantastic addition to a sadly marginalized tradition in American fiction: comics stories with LGBT protagonists.

But although comics about queer characters aren’t as common as they should be, they’ve certainly become more plentiful in the past few decades, as the medium has grown bolder and more experimental. Indeed, some of the best comics stories of recent years have starred LGBT characters (including Orlando’s acclaimed new series for DC Comics, Midnighter, about a lethal vigilante who happens to be openly gay). We asked Orlando — himself a bisexual man — to curate a list of ten great queer comics series. His sentiments on each follow.

The list ranges from Marvel and DC superhero series to autobiographical graphic novels. If there’s a through line, it’s this idea that Orlando articulated to us: “The gender and genitalia of the people we sleep with does not mean that we live in some alien planet. All of these books show the commonality of experience without fetishizing or silo-ing their worlds.”

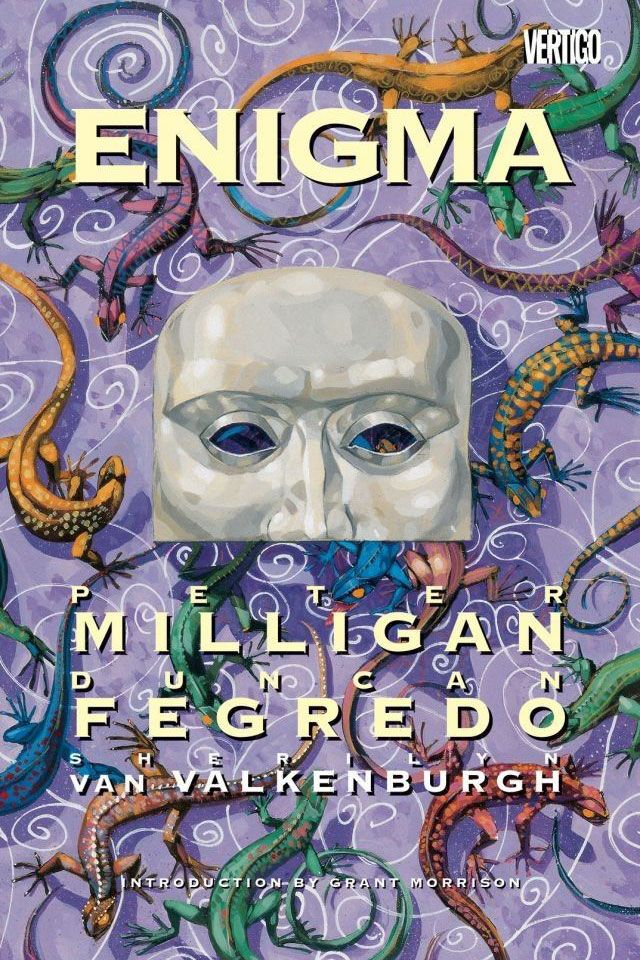

Enigma (1993), by Peter Milligan and Duncan Fegredo

“Enigma is the story of a guy who finds comics featuring a character named Enigma in his basement and, as he continues to carry on with his life, the character of Enigma seems to be appearing in the real world. It turns into a romance — kind of like if you grew up crushing on Robin, and then suddenly he was there and you were dating him. And on top of that, the character didn’t know he was queer before they met. It was provocative, especially at a time in the early ‘90s where comics weren’t really tackling these things in the mainstream yet. It was the first time I’d ever seen two guys naked in bed in a comic, postcoital. I’m perhaps a giant egotist and jackass, so I probably related the most to the all-powerful and omnisexual Enigma himself. Without spoiling the story, there’s a lot of questions about what makes sexuality and what makes our perceptions and — well, it was a great book for me when I was younger because it asked a lot of questions you would ask in your 17-year-old poetry class. Which is not much of a pejorative, because comics are about tackling these huge ideas with explosive fantasy tropes and a healthy dose of melodrama.”

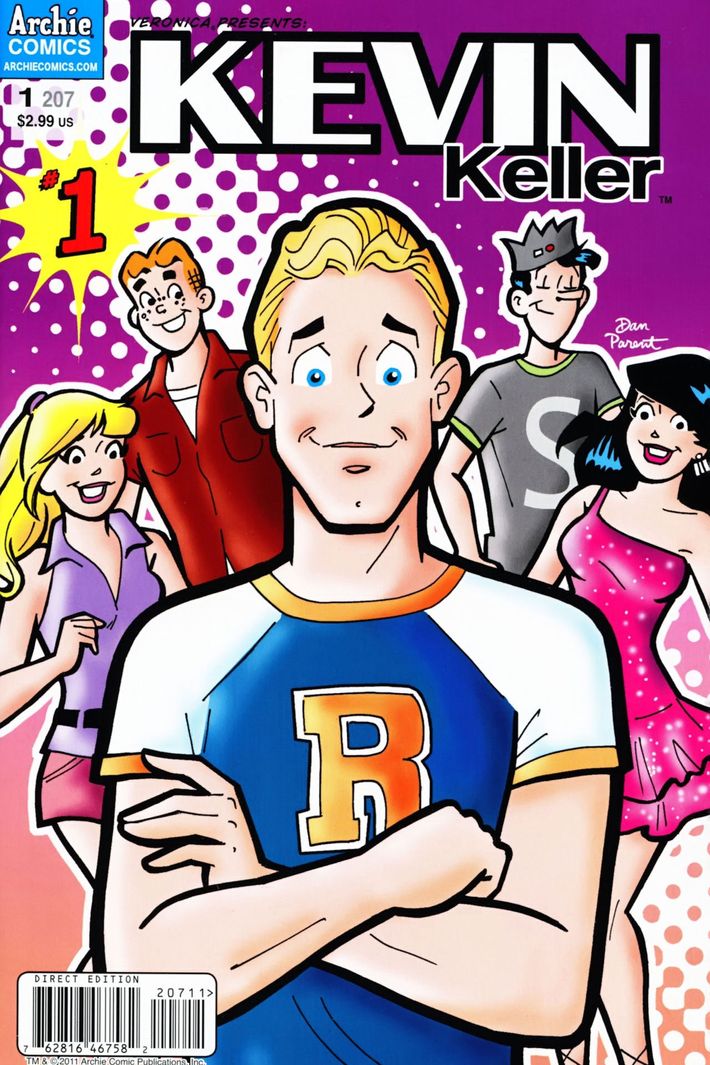

Kevin Keller (2012–2014), by Dan Parent

“This is the Archie book starring Kevin Keller, the first openly gay character in the Archie Comics universe. It’s everything it sounds like, and that’s why I think it’s wonderful. It’s a book set in the Archie universe, and it constrains itself to the dogma in the Archie universe while also being unabashedly gay. Kevin Keller infused the genre with gay themes and gay characters without having to change itself or without having to, again, sensationalize things. The question when Kevin was introduced was, ‘Oh, how could you do Archie with gay characters?’ Well, because Archie is perpetually virginal even though he’s torn between two women, and similarly, there’s more to being gay than just sexual contact. I think it’s progressive and brave to portray this type of gee-whiz, Archie-style romance between two guys.”

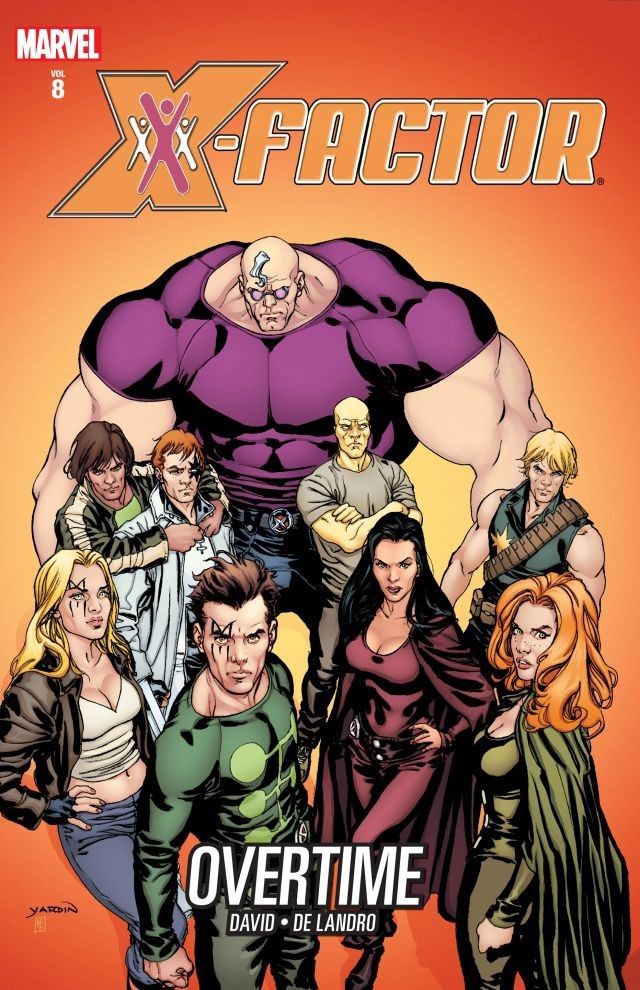

X-Factor Vol. 3 (2005–2013), by Peter David and various artists

“It’s all about Rictor and Shatterstar, two mutants in this superhero detective agency, and they’re a couple. Rictor identifies traditionally as a bisexual man, and Shatterstar chooses not really to identify at all, and drama obviously comes in from those two different worldviews and sets of expectations. This run was a great example of a straight writer who puts in the time and respect to depict a queer relationship in a way that is passionate, believable, and rich. Rictor-and-Shatterstar is interesting as a relationship because it’s an organic romance in the book, and it also deals with a lot of honest emotions. Shatterstar is not just bisexual, he’s pansexual. He’s a sexual explorer. You’ve got so many shades of grey. Much of the readership wants to put things in boxes and classify things, so the fact that you have so many different types of wider sexual identities is pretty trusting of the readership that they can handle it. Shatterstar, to me, is a hugely influential character; I spent my whole life saying you never have to choose how you’re identifying. I want to see a day when I stop hearing from bisexual people who are in same-sex relationships being pressured to identify as gay or lesbian by their partners, instead of their chosen identity as bisexuals. But I’ll never stop hearing that. That relationship between Rictor and Shatterstar, for all of its human faults, is truly one of a kind. Looking at queer comics isn’t complete unless you recognize the truly special thing that was happening in X-Factor.”

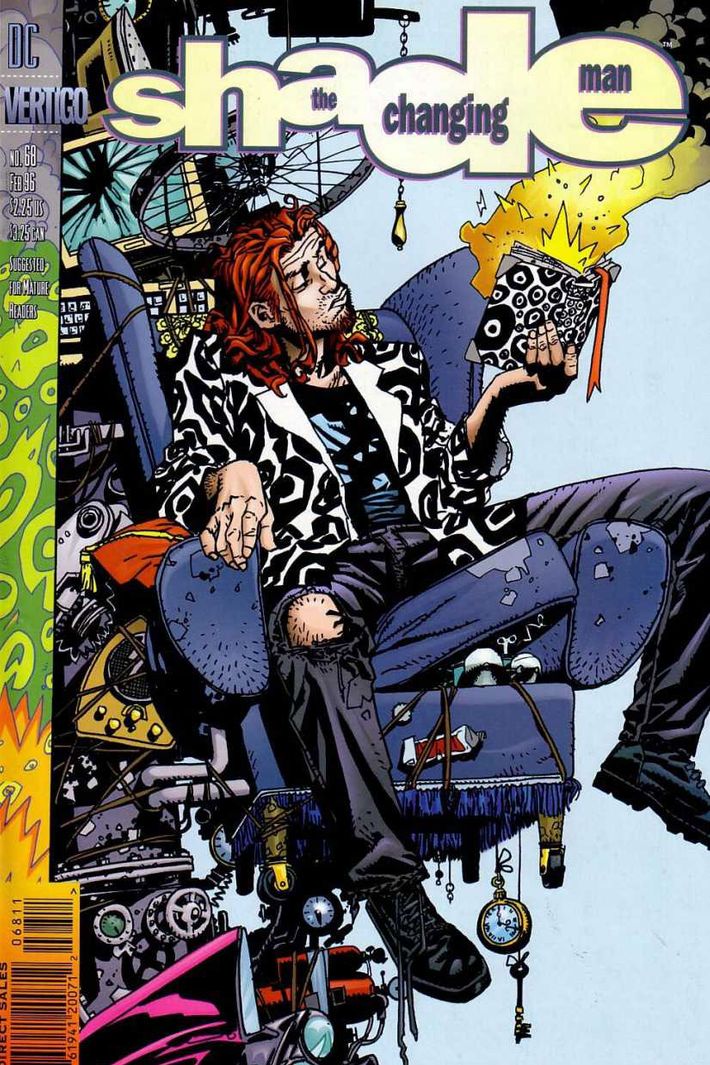

Shade, the Changing Man (1990–1996), by Peter Milligan and Chris Bachalo

“Shade covers a lot of trans issues. It’s about a person, Shade, who’s a policeman from a world called Meta and comes to our universe to study an entity called the Madness, which has escaped into Earth and is infecting America. What I love about Shade is that the queer themes are beautifully tackled, but it’s not the only thing it’s about. Shade is all about questioning structures and traditions — things that we consider absolute. In doing so, of course, it tackles absolutist notions of sexuality and gender, especially in the form of Shade himself, who can easily become a woman. It’s also about a concept of madness in general and these huge moments that we have as a country. Milligan is British, and some of the best books about American culture come from people who don’t have the cultural associations we have with some of our own American mythology, so I was in love with Shade from the first story arc, which is about our obsession with John F. Kennedy. The perspective it takes on America and masculinity and world culture as it is in the 1990s is pretty invaluable. It’s a book that probably could not have been published today, because it’s a slow burn and very few people get punched.”

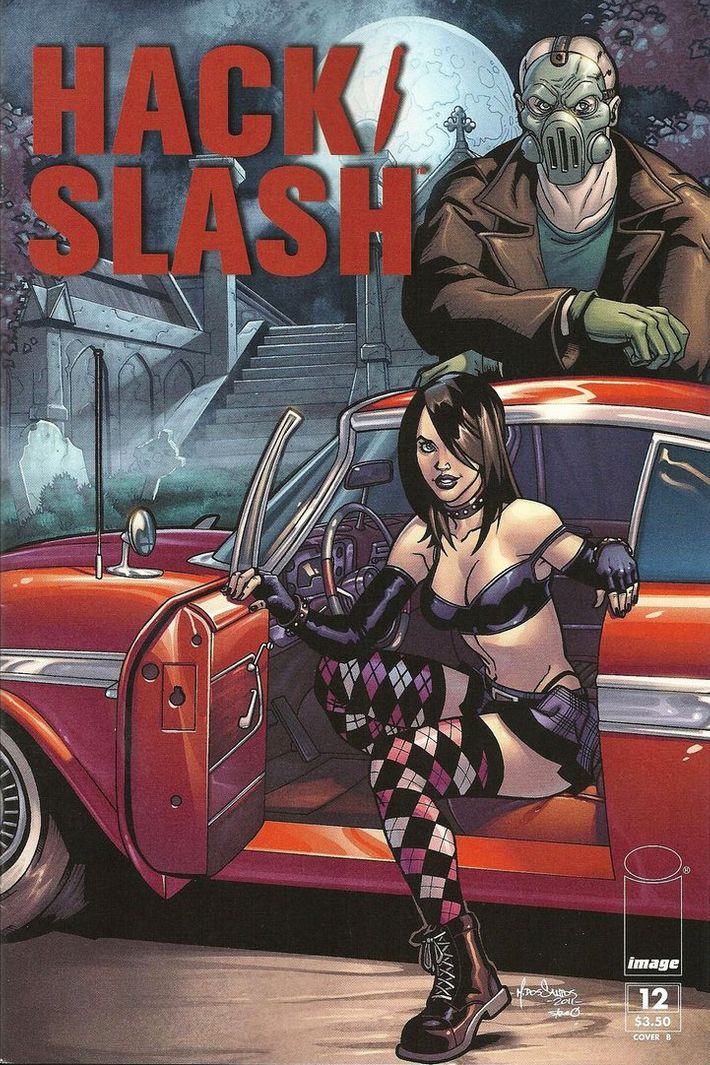

Hack/Slash (2004–present), by Tim Seely and Emily Stone

“This is in for the same reason Kevin Keller makes the list: They’re taking different pieces of genre fiction and giving them queer leads in a way that’s not a marketing ploy. Hack/Slash features a strong female lead character in a realm traditionally reserved for masculine guys. It’s about a woman who’s escaped a slasher-movie plot and now makes a living hunting down stereotypical movie killers like Freddie Krueger and Jason. You have a subversion of that trope. The ‘final girl’ from slasher movies is now at last the hunter and sort of taking the proactive role of power in those movies from other characters, so I think it’s a bold and subversive thing that really deserves all of the credit it should be getting for something that it has been doing for over a decade. It’s been dedicated to dealing with bisexuality, but didn’t make a big deal out of it. They were just quietly doing the right thing for a long time.”

Flutter (2013), by Jennie Wood and Jeff McComsey

“Flutter is a great premise. It’s about a teenage girl who shape-shifts into a boy in order to romance another girl. You have this dirtier Archie setup, which is not a bad thing. It’s sort of like the next step of what we’ve said about Kevin Keller. It’s by Jennie Wood, a queer female creator, and deals with trans issues in high school in a very obviously teen-romantic idea: The hero just wants this person so much that she ends up changing herself to get her. It has a meaning for adult issues, of course, but at the same time, there’s the perfect amount of whimsy in it and sort of fairy-tale logic. And Jennie Wood is an amazing queer creator and leader of a rock band. She kicks all kinds of ass.”

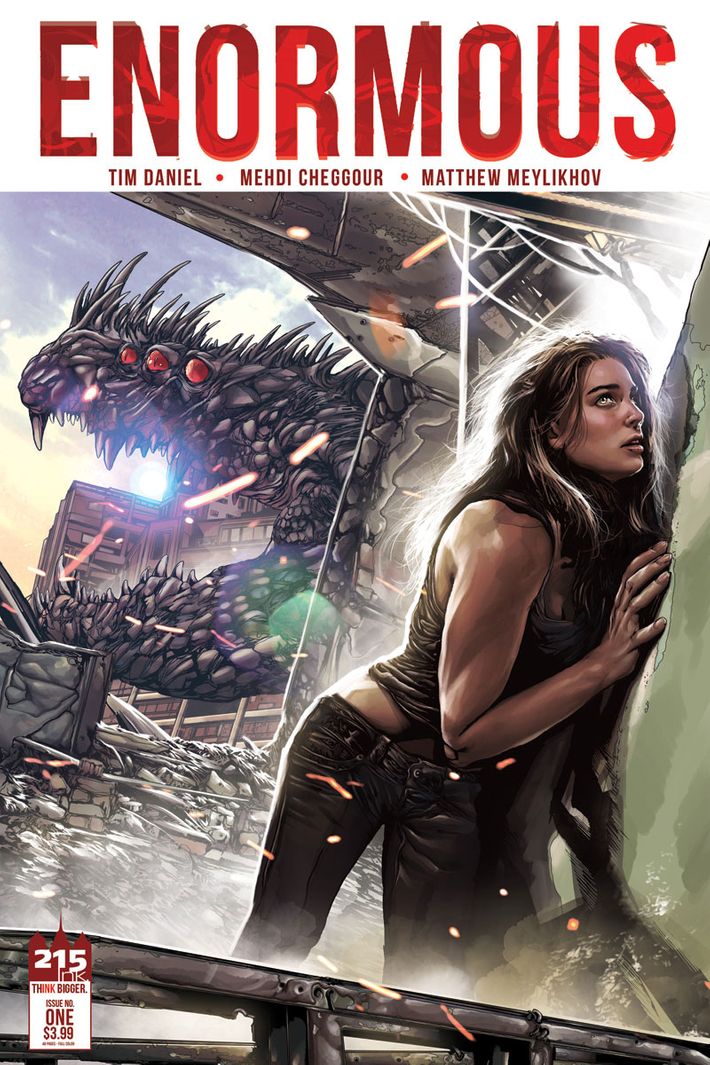

Enormous (2012–present), by Tim Daniel and Mehdi Cheggour

“Enormous is the Walking Dead of monster movies translated into comics. It’s sort of like people living in the world of Stephen King’s The Mist, or people living in the world of Pacific Rim if we were never able to fight back. It’s postapocalyptic, with enormous monsters roaming the earth and creating danger at every turn. And the lead is a queer woman of color. The weight of the narrative is put on her, without any restraint. Some books that I put on here are about being trans or about being queer, and other are just great genre narratives that aren’t ashamed to feature queer leads. That’s what Enormous is. You read the first issue, and it’s a woman kissing her wife or girlfriend before she goes off to fight this giant monster. And it’s presented with just the same amount of normalcy, and just the same nonchalance, that you’d expect if that scene were to go down if the character was heterosexual. By not making a big deal out of it, by not sensationalizing it, it’s bold and vitally important. Plus, it’s a book about enormous, person-eating monsters!”

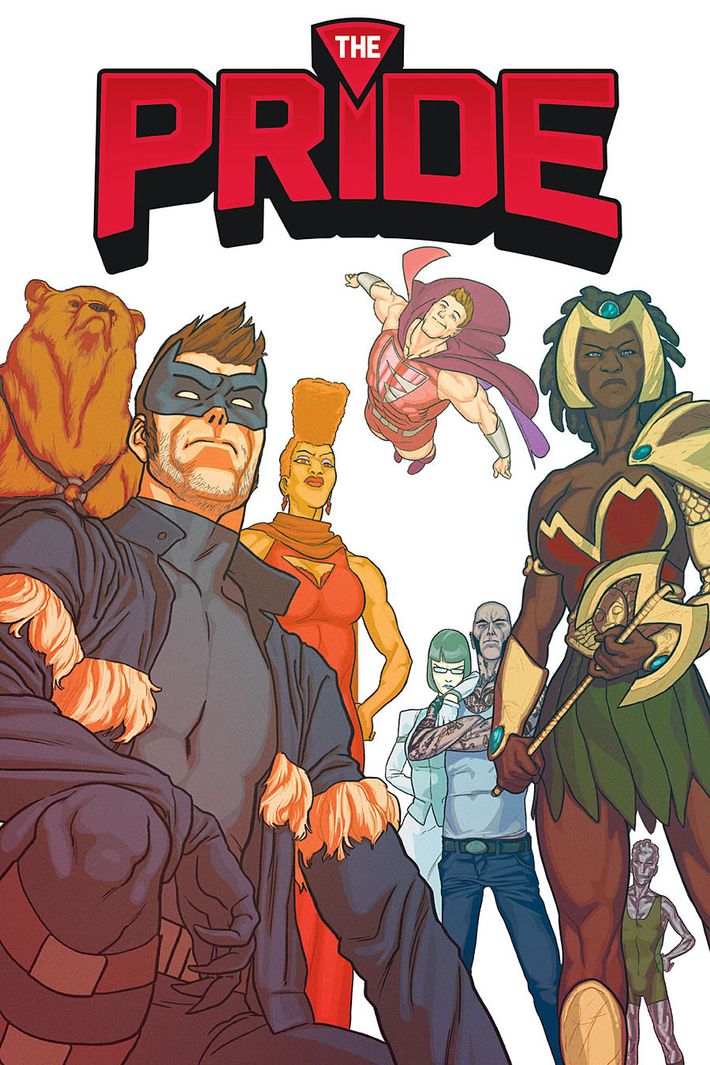

The Pride (2014–present), by Joe Glass and various artists

“The Pride is basically the gay Justice League. The series comes from a great writer, Joe Glass, and it features a bunch of different queer superheroes from across the spectrum of sexuality and gender. This is in many ways the most overtly queer, the most unbowed, gay book on the list. The world of superheroes is a world of melodrama. It’s a world of intensified reactions. It’s basically pro-wrestling with superpowers instead of steel chairs. So here’s a time when I think that these loud, bright characters are wholly appropriate and wonderful. It’s a world than can afford to be — just like you had in Kevin Keller — a little more utopian. You don’t necessarily have to acknowledge the negative undersides and dangers as much. You can send this type of purely positive message, this optimistic message, with a superhero team. It takes the modern myth of our time — superheroes — and owns it completely for the queer community. Having our own myths is also incredibly important.”

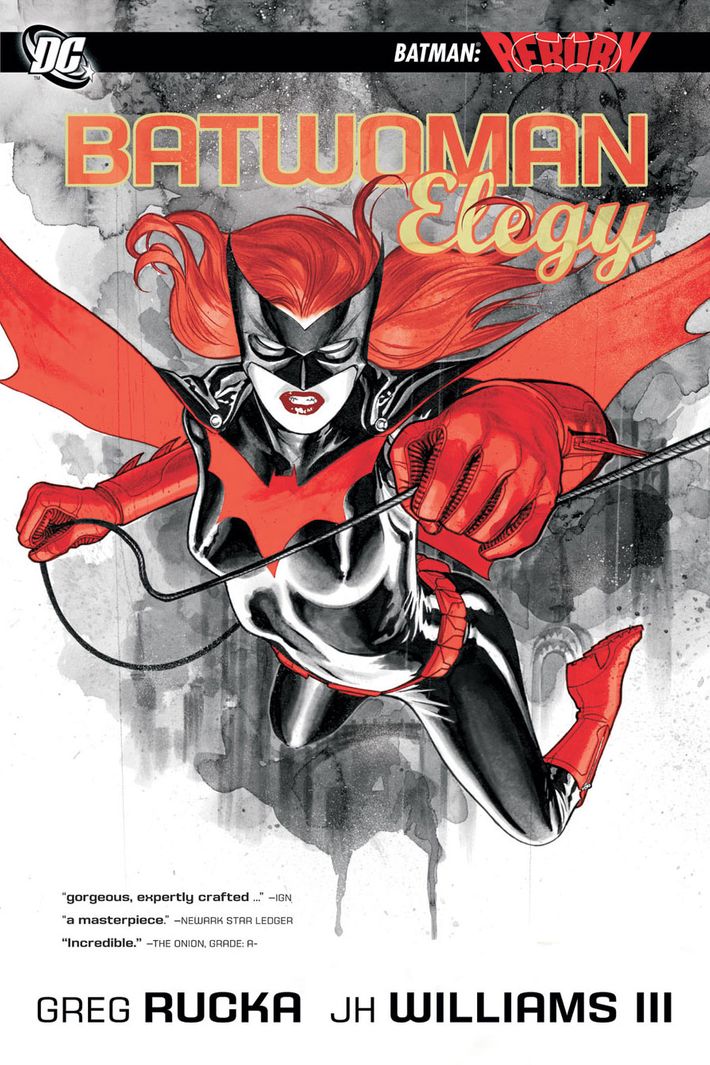

Batwoman: Elegy (2009), by Greg Rucka and J.H. Williams III

“This is the origin story of the ultimate outsider of the Batman family. Everybody else with a “Bat” in front of their name is someone who answers to Bruce Wayne, but Kate Kane is different. She’s someone who’s outed in the military and forced to leave, and so she has to find a different way to serve, and she serves by becoming the only vigilante in Gotham who can really stand toe-to-toe with Batman — which is a pretty amazing thing for the first major lesbian character in DC Comics to do. When it came out, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was still around, and this was one of the most modern origin stories that you’ve had: The villains in Batwoman’s origin aren’t some killer in an alleyway; it’s a society that won’t let her be who she is. Batwoman is on this list for treating her like a person, for imbuing this type of totemic origin story when it comes to the Batman origin stories with a truly topical and toothy bent that I think is amazing. And Batwoman is a lesbian, but it wasn’t about butching her up. It’s about just telling a story about one person with depth and realism. They utterly respected the character and her problems in a way that shows that they were not taking their responsibility lightly in creating this character.”

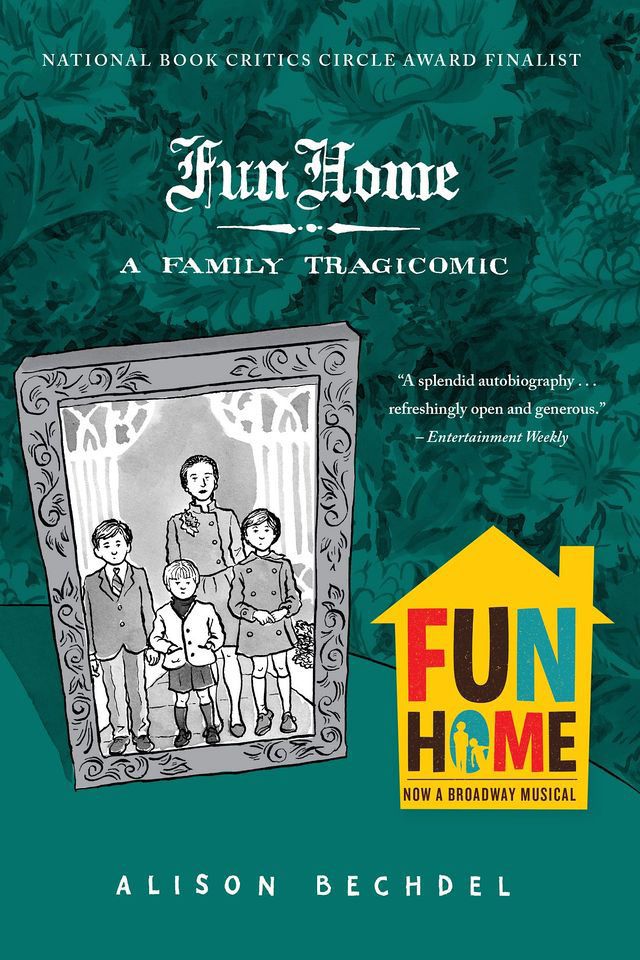

Fun Home (2006), by Alison Bechdel

“There’s not a lot to say about Fun Home that hasn’t already been said, but you can’t have this list without it being on there. It’s revolutionary. It takes these slice-of-life stories that have so pervaded independent comics media and gives a naked and raw look at one woman’s life. It’s almost a little rote to mention Fun Home, but that’s only the case because of how pervasive its influence is today. In many ways, it’s a keystone to all the things that would come after it.”