A typical musical might list 18 numbers in its program; Hamilton, with 34, is more in the range of operatic works like Porgy and Bess. Ambition is part of it, no less for Lin-Manuel Miranda today than for George Gershwin in 1935. So is scope. The true-life tale of the orphan immigrant turned architect of American federalism (with sidelines in battle, banking, bedding, and duels) could not be told, at least not with depth to counterweight its breadth, in a few ditties and choruses. Nor could Miranda’s overarching point — that the doors of history must especially be opened to those traditionally excluded from it — be made in the traditional forms. When Hamilton debuted Off Broadway at the Public Theater in February, the rapturous reviews, including mine, all hailed its “groundbreaking” incorporation of contemporary musical genres, especially rap and various forms of hip-hop, as a way of refurbishing and selling an old story. A second look, as the slightly revised musical opens on Broadway for what will no doubt be a long and profitable run, suggests that something even more significant is going on. The breakthrough isn’t so much the incorporation of those contemporary genres; after all, Miranda already did that, throwing in Latin music to boot, in the charming In the Heights. But Hamilton not only incorporates newish-to-Broadway song forms; it requires and advances them, in the process opening up new territory for exploitation. It’s the musical theater, not just American history, that gets refurbished. And perhaps popular music, too. Call it Miranda’s manifest destiny, though one dreads the caravans of poor imitators that will surely trail behind.

The most noticeable benefit of the hip-hop infusion is density; not only are there a ton of songs, but each is crammed to the margins with words. (The opening number, simply called “Alexander Hamilton,” has more than 500; “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” to pick a classic almost at random, has about 70.) This allows Miranda to keep lots of tracks going at all times instead of having to alternate among them: In each lyric you sense he is keeping his Argus eyes open to the immediate plot point, motivation and subtext, the general chronology, the introduction and development of larger themes, character establishment, dramatic structure, variation of tone, staging opportunities, and, oh yes, pure musical enjoyment. But the laxer “rules” of rhyming in hip-hop — basically, any kind of assonance or consonance or slant rhyming works, as long as it alerts the ear to something meaningful — do more than that, providing approximately the same enhancement to the narrative as the mostly nonwhite casting does to history: They both offer new ways of connecting ideas. I’m not just talking about the brilliant verbal fusillades that stud the score (and get big laughs):

You think I’m frightened of you man? We almost died in a trench

While you were off getting high with the French.

Thomas Jefferson, always hesitant with the president,

Reticent — there isn’t a plan he doesn’t jettison.

Madison, you’re mad as a hatter, son, take your medicine.

Damn, you’re in worse shape than the national debt is in!

Even more powerful than such peacockery is the subtler wordplay that makes you nod with understanding. In that opening number, for instance, Miranda pairs the name Alexander Hamilton with the phrase “a million things I haven’t done” — say them both out loud to appreciate the alignment of sounds — thus permanently joining, in the audience’s ear, the main character with his main quality: impatience to make a mark. Hammerstein would have cringed, yet this and a slew of other verbal leitmotifs, none available to the traditional lyricist, work perfectly to tag each character and, through variation, mark his or her development.

And what of the show’s development? I noticed only a few textual changes since it opened downtown, all smart. The role of the villain, Aaron Burr, has been carefully streamlined (the needless reprise of one of his songs is gone) to keep him as closely tied to Hamilton as possible. The paradoxical result is that Leslie Odom Jr.’s already excellent performance is even more thrilling. Similarly, a second-act song called “The Last Ride,” about President Washington’s quashing of the Whiskey Rebellion, has been retooled as “The Last Time,” about his decision to forestall an imperial presidency by stepping down after two terms. (Hamilton helped write the farewell address.) In all cases the changes tie the narrative more tightly to its main character and thus favor a more emotional reading of history, at the loss of only a few facts. It’s a good trade-off; in almost three hours, which fly by, plenty of facts remain.

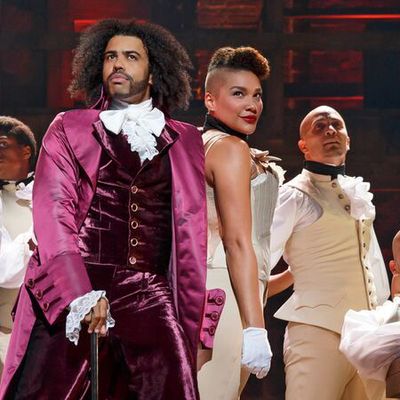

There are so many ways such trade-offs could have gone wrong. Miranda’s ambition could have outstripped his craft. The weight of inviolable historical reality could have rendered the story humorless. Even having avoided those pitfalls, the show faced other dangers: The expansion for Broadway could have burst its balloon. And though none of these things happened, there were nevertheless a few moments re-watching it when I, as a critic if not a lay theatergoer, could have been tempted to pick at a scab. The treatment of the story’s women — Eliza Schuyler, who becomes Hamilton’s wife; her sister Angelica, who becomes his romantic friend; and Maria Reynolds, a mistress who betrays him — particularly invites questions, even though Miranda has clearly taken pains to at least acknowledge the way history (and his story) have sidelined them. (Eliza gets Hamilton’s moving, final word.) I still wonder, too, if the manic staging by director Thomas Kail and choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler, fun as it is, may sometimes get in the way of the action instead of enhancing it. And Miranda himself has perhaps been too busy. His voice starts out strong but quickly acquires a ragged edge that tends to separate him from the preternaturally robust singers around him, including Odom, Christopher Jackson as Washington, Phillipa Soo as Eliza, Renée Elise Goldsberry as Angelica, Daveed Diggs as Jefferson, and, in the plum comedy role of George III, delicious Jonathan Groff, replacing Brian D’Arcy James. But that, like all my other cavils, is far outweighed by everything that’s great, and anyway might be an advantage. Hamilton is separate from everyone around him; it makes sense that he should sound that way too.

The same goes for Hamilton. Like all truly living things, it has evolved its own unique necessities from what its past already provided. That’s history, too. So let’s not call Hamilton groundbreaking. Let’s call it, with hope for the future, historic.

Hamilton is at the Richard Rodgers Theatre.