On her current tour, the Norwegian avant-pop performer Jenny Hval has been “covering” Lana Del Rey’s breakout hit “Summertime Sadness.” During some performances, she sings or lip-syncs along with the album track while she stares at her smartphone, languidly swiping through prospective suitors on Tinder. When I saw her play at the Basilica SoundScape festival in Hudson, New York, the setup was even more conceptual: Two of her backup singers sang the song — during the final repetition of the macabre chorus line, “I got that summertime, summertime sadness,” they erupted into theatrical sobs and horror-movie screams — while Hval, provocatively blank expression on her face, recorded our bemused expressions on her phone. Like Del Rey herself, Hval has a fully realized stage persona and an impenetrable poker face, so it was difficult to tell if the whole thing was a jab or an homage to the artist formerly known as Lizzy Grant. The overall effect was something between the two, as if Hval was saying, Isn’t it weird that this bizarre, glacially paced ballad about a particularly feminized strain of depression was a pop smash? And it is, when you think about it. When it was over, Hval told us that what she liked best about Lana Del Rey was that the tempo of her music was, as she put it, “perfect to swipe to.”

Okay, that last part probably was a jab, but it brings up an interesting point. Even though her sound and aesthetic are proudly retro, something about Lana Del Rey’s music — and the particularly modern kind of sadness it embodies — feels like the creation of a brain that has been lobotomized by the internet. You know that mind-numbing feeling when you can’t remember how long you’ve been scrolling through Twitter or Instagram? That is kind of what it feels like to listen to a Lana Del Rey song. The cultural references that pepper her songs like hyperlinks are Wikipedia-deep, so obvious and clichéd that a generous listener would say they’re making a conscious point about the impossibility of originality in the postmodern age. (A few sample lyrics from recent Lana Del Rey songs: “Born to be wild”; “Nothing gold can stay”; Like an endless summer”; “Like an easy rider.”) And yet at the same time, there’s a heavy pull in Del Rey’s music — and particularly on her lush, backward-glancing new album, Honeymoon — against the current of the times, as though she’s trying to gift her dressed-down, hyperproductive generation with a sense of glamour and leisure it has been denied.

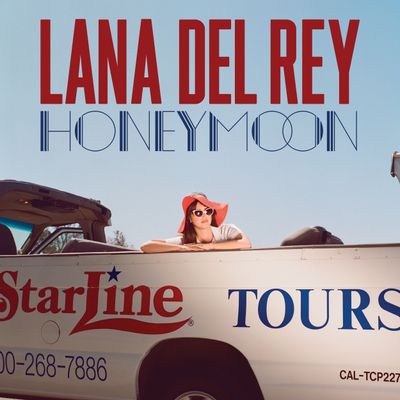

Honeymoon is the first Lana Del Rey album to simply exist on its own terms, free from the internet’s cycle of backlash, and backlash to the backlash, and backlash to the backlash to the … well, you get it. The controversies that have surrounded her from the start (the claims that she’s anti-feminist, “inauthentic,” and romanticizing self-destructive behavior) have died down, simply because she has continued to do her thing: making singular, peculiar music that has been accurately described as “Hollywood sadcore.” Like all of her other records, Honeymoon is a dreamscape — an immersive, escapist fantasy into a world of bad boys, strong weed, and lush, billowing melancholia.

Del Rey makes music about hollowness and American ennui, and many of her lyrics are almost brazenly empty. For example, all weekend I have been staring into the abyss of a particular lyric from the seventh track, a hazy, molasses-slow ballad called “Art Deco”:

You’re so Art Deco

Out on the floor …

Baby, you’re so ghetto

You’re looking to score

What does it all mean? That is generally the wrong question when it comes to Lana Del Rey. To appreciate her is simply to be morbidly fascinated by the mind that would write those words and think, Yep, there’s the chorus. Her lyrics are anti-striving, both in their message and the imagined facts of their composition. She delivers many of the lines on Honeymoon as though she might fall asleep before the song has finished; she writes like someone who has given up on language midway through the construction of the lyric. (“Looking back, my past,” she sings on the listless “Freak,” “It all seems stranger … than a stranger.”) By now Del Rey is so committed to her aesthetic that she’s turned her own gaucheness and gracelessness into their own virtues: In the mouth of almost anybody else, “You’re so Art Deco, out on the floor” would be a bad lyric, but it is actually the quintessential Lana Del Rey lyric. It’s so audacious in its laziness that it becomes something glorious, transcendent, tweetable. Two different people have texted it to me this weekend, because it is such perfect shorthand for Honeymoon’s odd, carefree WTF-ness. It is the perfect Lana Del Rey lyric because I know that it will never truly give up its secrets, and I know deep down that it means nothing, yet I cannot stop staring into that abyss.

Honeymoon is, for stretches, an uncomplicatedly gorgeous record. The best songs balance Del Rey’s blasé, shrugging perspective with classically beautiful melodies and elegant arrangements. The sumptuous single “Music to Watch Boys To” sounds like a night at the Copacabana when the entire band is on Klonopin; the stirring, twangy, tumbleweed roll of a ballad “God Knows I Tried” is among her best songs. I will admit that I laughed when I saw a song on this record that was credited to “Del Rey/T.S. Eliot,” but the interlude in which she reads the poet’s “Burnt Norton” atop a bed of pastoral electronica is actually stunning and deeply felt (mark her utterance of “time present, and time past are both perhaps present in time future” as the moment I finally understood Lana’s fascination with space). I actually wish this moment lasted longer than its minute and 22 seconds. I am shocked to admit it, but I think I would gladly listen to Lana Del Rey read the entirety of “The Waste Land.”

But unfortunately, there’s too little variety on this album to make it a compelling listen from front to back — the tempo of nearly every song is identical. This is forgivable for the first half-dozen songs, but by “Art Deco,” Honeymoon has become a sonic sedative. Del Rey begins to retread old provocations: The half-baked “Religion” plays out like a less interesting update of Ultraviolence’s “Money Power Glory”; a nondescript cover of “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” one of the album’s biggest missed opportunities, only recalls her more inspired rendition of “The Other Woman.” At times, Honeymoon feels like it’s ramping up to make grand statements about love, longing, and the emptiness of the American Dream, but in the end, it mostly feels like a big, cosmic shrug.

And yet there’s something admirable about how strange and utterly un-commercial this record is. As far as Lana releases go, this is actually nothing new. One of the weirdest curios floating around during the release of last year’s Ultraviolence was the “radio mix” of the atmospheric single “West Coast” — it was fascinating to hear how much producers had to tweak her vision to even attempt to make it conform to radio, and even then it was obvious that this version was inferior to the slithery, shape-shifting original. If nothing else, Honeymoon represents a kind of full-circle moment for the space Lana Del Rey occupies in our culture. When she first appeared on the scene with her DIY-crooner anthem “Video Games,” the indie-rock underground treated her like a threat to its very existence. Four years later, she feels like one of the last flag-bearers of all the virtues it once held dear: The primacy of the album over the single, nostalgia for the guitar-rock and American psychedelia of eras gone by, an utter disinterest in selling out to appeal to a wider audience. For better and sometimes for worse, Lana Del Rey has become our most independent-spirited pop star.