Earlier this week at the Toronto Film Festival, a few of my colleagues and I were puzzling over one of the fest’s most surprising flops, Freeheld. “What the hell happened with that movie?” I asked, as everyone just shook their heads ruefully. On paper, Freeheld seemed to have everything going for it: It’s based on an Oscar-winning short documentary about cancer-stricken police officer Laurel Hester (played here by Julianne Moore), who fought political red tape when a New Jersey board of freeholders refused to grant pension benefits to her domestic partner, Stacie Andree (Ellen Page). Alas, the actresses fail to strike up any sparks with each other; the dialogue and direction are flat; and the less said about Steve Carell, who arrives at the halfway point as a flamboyant gay activist, the better.

“But at least Michael Shannon was good!” someone said, and we all nodded. As Dane Wells, the straight-but-not-narrow cop who partners with Hester and eventually becomes her greatest ally, Shannon gives the film’s lone terrific performance. In fact, by the end of Freeheld, Moore and Page have practically been relegated to background players so that the formerly reticent Shannon can rally the troops and deliver a final knockout monologue.

“It’s really his story,” said one of my colleagues, and when I heard that too-familiar line, I sighed. This year’s Toronto Film Festival lineup is full of movies that feature queer and trans characters, but why does it seem like deep down, these films are still about straight people?

Just look at the reaction to The Danish Girl, for instance. That 1920s-set film chronicles the complicated marriage between Copenhagen artists Einar and Gerda Wegener (played by Eddie Redmayne and Alicia Vikander), who find their bond tested as Einar’s true gender identity comes to the fore. The two move to Paris so that Einar can live more authentically as Lili Elbe, and though the initially supportive Gerda finds artistic fulfillment through painting Lili as her muse, she still sometimes mourns the loss of her husband.

That film has a knockout central character to mine in Lili Elbe, so why does The Danish Girl feel like it’s really Gerda’s story? Some credit must be given to Vikander’s unexpectedly forceful performance: The Ex Machina star is terrific in this movie, dominating every single scene she shares with the Oscar-winning Redmayne. “Alicia Vikander May Be the Real Winner From The Danish Girl,” one Variety headline posited after the film’s debut, and it’s hard to argue, given the Vikander-mania that seems to have swept Toronto. This is perhaps the most significant performance in the Swedish star’s terrific, prolific year, and she deserves all the laurels she’s about to get for it.

But the film’s character imbalance can’t be laid at Vikander’s feet alone, because The Danish Girl is scripted from the start to both begin and end with Gerda; in fact, I’d wager that Vikander is granted more screen time than even the first-billed Redmayne. And while both Gerda and Lili have their own solo scenes and story lines, nearly all the screen time that they share together clearly favors Gerda’s perspective: Tellingly, there are several scenes that follow Gerda home as she is expecting to see Einar and finds Lili there instead, treating the film’s ostensible protagonist as a surprise to us and clearly grounding Gerda as the audience surrogate. (Another character even refers to Gerda, not Lili, as the film’s titular “Danish girl.”) In real life, Gerda eventually split from Lili and moved with her new husband to Morocco, where she was living when she learned of Lili’s death; the movie, however, keeps Gerda near Lili’s side until the very end. I’d like to think that was a historical revision meant to give The Danish Girl’s central coupling an emotional payoff in the third act; my cynical side, though, wonders if the filmmakers simply couldn’t bear losing the straight cisgender character.

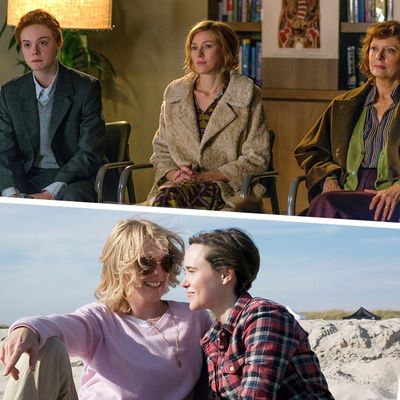

The Danish Girl isn’t the only trans-themed film making waves in Toronto — there’s also About Ray, starring Elle Fanning as a transitioning teenage boy. Ray’s mother, Maggie (Naomi Watts), frets over signing the papers that will authorize his testosterone treatment; meanwhile, Ray’s lesbian grandmother, Dodo (Susan Sarandon), still refers to Ray by his female birth name, Ramona, and tries to talk him out of the transition entirely. As the title would indicate, nearly all the characters’ plots revolve around Ray, but the film treats him more as an inciting incident than a protagonist, and again, it’s telling who the film favors whenever the three actresses share a scene together: Aside from an opening snippet of narration from Ray that the movie never reprises, filmmaker Gaby Dellal skews things so thoroughly toward the character played by Watts that The Playlist noted “the film might more accurately be titled About Maggie.”

Now, I’m not saying that it was a mistake to position Watts at this movie’s center: Quite the contrary, as it allows her to give a loose and funny star performance and frees Watts from the “supportive love interest” role she’s been consigned to for her last few movies. Nor am I saying that just because a movie features a gay or trans character that that character deserves to be the undisputed lead: I’d like to see more movies where that is the case, but I’d also like to see more movies with gay or trans characters, period, and it will be a major breakthrough when those characters are able to simply exist as part of the tapestry of a film, with plots that don’t always pivot around transition or coming out.

And while I hope that queer and trans directors will get to tell some of those stories, I’m not blind to the fact that most filmmakers in Hollywood are straight and cisgender — like the directors of the three movies I’ve mentioned — and I don’t want to suggest that they’re not allowed to tackle these characters. I just don’t want them to do it to the exclusion of the people who have really lived these lives, because I suspect that a trans filmmaker would be able to foreground Ray in a way that Dellal does not, or make us privy to Lili’s emotional preparations on those nights in The Danish Girl when Gerda comes home to her and not Einar.

Both of those films and Freeheld seem almost stymied by the sheer determination on display from Laurel Hester, Lili Elbe, and young Ray; these characters know exactly what they want and pursue it doggedly, but the filmmakers don’t always know how to dramatize that single-mindedness, instead finding juicier opportunities in the conflicted characters who orbit our queer and trans leads. Their arcs then become the most varied and the most important in the film, and that’s a shame. Make no mistake: I’m glad that these stories are finally being told, and with top-tier filmmakers and performers, to boot. But if these movies are being made because the queer and trans characters are so fascinating, let’s keep those characters at the center, where they belong.