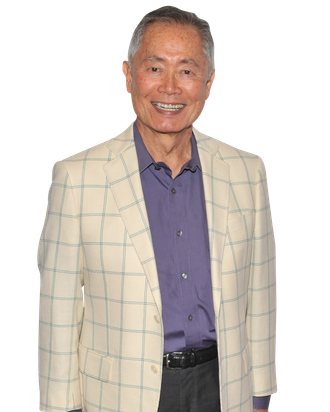

Star Trek┬áalum George Takei may be best known these days for his delightful online presence, but heÔÇÖs completely serious about his latest project:┬áAllegiance, a new Broadway musical based on his own familyÔÇÖs experience in U.S. Japanese internment camps during World War II. Four decades after moving to New York in hopes of making it Off Broadway, Takei, at 78, will make his Broadway debut in the show. Over a lengthy breakfast, he chatted about his memories of the internment, his tendency to cry at the theater, and the surprising degree of overlap between Trekkies and theater nerds.

I see youÔÇÖre drinking green tea ÔÇö is that part of your survival-on-Broadway routine?

Oh, IÔÇÖm a green-tea addict. Antioxidants. A longevity libation! My grandmother loved green tea ÔÇö not with lemon, thatÔÇÖs my addition ÔÇö and she lived to 104.

Seems like a good plan. For how long had you wanted to do something dramatic with your familyÔÇÖs story?

It happened eight years ago, when my husband and I met Jay Kuo [who wrote the music and lyrics] and Lorenzo Thione [who co-wrote the book] ÔÇö actually, we met two nights in a row, which seems like coincidence but I think was meant to be. The first night we were at Forbidden Broadway┬áÔÇö IÔÇÖm an Angeleno, but we have an apartment here, and while weÔÇÖre here we go to the theater almost every night. We got there early and were sitting there chatting, and two guys sat right in front of us ÔÇö one was Jay, one was Lorenzo. Jay recognized my voice and turned around and said, ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre George Takei!ÔÇØ We chatted awhile, and after the show we went back to our apartment and said, ÔÇ£Wow, those guys are true theater loversÔÇØ ÔÇö it was palpable. The next night we went to see In the Heights, and we looked down our row and saw two arms waving at us ÔÇö the same two guys.

And IÔÇÖve heard it was something about In the Heights that moved you to think about your own story?

Near the end of the first act, the father sings a song titled ÔÇ£Inutil,ÔÇØ which is very moving, about a fatherÔÇÖs love for his daughter and feeling useless because he canÔÇÖt help her. That triggered my memory of a discussion I had with my father as a teenager.

We had many discussions about the internment at dinner. He was open to talking about it, which was extraordinary  this story is not well known, even among Japanese-Americans, in part because the people of my parents and grandparents generations were so wounded, they didnt want to talk about it. They knew Dad and Mom were in camp  thats the term used  but thats all. I challenged my father a lot, and one conversation I still regret to this day, I said, Daddy, you led us like sheep to slaughter to the camps. [Pauses.] The give and take suddenly ended  he was silent. I sensed I had hit a nerve, I had hurt him. That silence seemed to be an eternity. Finally he looked up at me and said, Maybe youre right, went to his bedroom, and closed the door. I felt terribly. Theres no one more arrogant than an idealistic teenager! I realized this man, to whom I owe so much  who suffered so much during that period 

So anyway, I heard this song in In the Heights, and it reminded me of this conversation with my father, and I was bawling. IÔÇÖm a crier! Then, immediately after that intermission comes, and Jay and Lorenzo came clambering over to ask why that song hit me so profoundly. I told them and they became very, very interested. I told them it had always been my intent to write a drama based on the first third of my autobiography, about my childhood, and Jay said, ÔÇ£Oh, no, itÔÇÖs got to be a musical ÔÇö music hits you more profoundly.ÔÇØ And of course, as a musical-theater fan, I was interested.

Did you ever question whether a musical was the right format for this story? The subject matter is more serious than the typical musicalÔÇÖs.

It doesnÔÇÖt remind you of Cabaret, about the rise of Nazism, or Les Mis├®rables, about the French Revolution? All musicals have powerful human experiences at their center ÔÇö Lea [Salonga] was first seen in Miss Saigon, about the Vietnam War! ItÔÇÖs not all leg-kicking, sparkly, happy-happy. Real musicals have great, profound human experiences at their center.

What were you like as a kid? Do you have any concrete memories of the internment experience?

I do remember there was no privacy; some of the units were shared by two families, and they put up bedsheets to separate the real estate, as it were. My parents would go off on long walks around the block, and when they came back my mother often had bloodshot eyes ÔÇö sheÔÇÖd been crying. I was there for four years. ItÔÇÖs vivid, but itÔÇÖs the memory of a child. We were incarcerated first in southeastern Arkansas, and┬áI have to admit, I had fun catching pollywogs and playing games. But another ironic memory I have is, I started school in a barrack, and every morning began with the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag ÔÇö and I could see the barbed wire right outside the window as I recited the words, ÔÇ£with liberty and justice for all.ÔÇØ And because my parents answered no to question 28 on the government questionnaire, we were transferred to an even harsher prison. So I was in two camps.

How did the questionnaire work?

Question 28 was one question with two conflicting ideas: Will you swear your loyalty to the United States of America, and forswear your loyalty to the emperor of Japan? WeÔÇÖre Americans! For the government to assume that we have a racial innate loyalty to the emperor was offensive. If you answered no, you were answering no to the first part as well; if you answered yes, you were confessing. Like, ÔÇ£When did you stop beating your wife?ÔÇØ ÔÇö it was a horrible question, stupidly worded. And the amazing thing was thousands of young men swallowed the bitter taste and answered the way the government wanted them to, and went to fight for this country ÔÇö the 442nd combat regiment. They were resistors; they said, ÔÇ£I will fight for my country as an American, not as an internee, reporting to their hometown draft office.ÔÇØ It was a very principled, very American, gutsy stance, and for that they were tried for draft evasion, and I consider them heroes, along with those that died and those that came back.

Back to the musical ÔÇö Jay and Lorenzo are first-timers as writers on a Broadway musical. What convinced you they were up to the task?

We didnÔÇÖt know anything about Jay as a composer/lyricist ÔÇö and there are many composer/lyricists. I told them about the word gaman,* which is in the musical. It means ÔÇ£endure,ÔÇØ but to maintain your dignity. Jay was very moved by that. About three weeks later, he sent me a song titled ÔÇ£Allegiance.ÔÇØ And there I was at my computer, blubbering away. ┬áAlas, the title remains, but the song is gone! But thatÔÇÖs when I realized, this guy can really write powerful music.

How did your love of musical theater start?

In downtown Los Angeles, we had the Biltmore Theater, where all traveling road shows came through, and I made friends as a high-school student with the house manager, and she allowed me to see plays for free if I ushered. So the first musical I saw there was Kismet. ┬áI was transported! And then the musical I fell in love with via a record was Flower Drum Song. Pat Suzuki and Miyoshi Umeki were on the cover of Time magazine, which was mind-boggling for a young kid, to see two Japanese-American faces on the cover of Time. I didnÔÇÖt see it onstage until much later. In December of 1960, I came to New York chasing the civil-rights musical IÔÇÖd performed in in college, Fly Blackbird, and was walking by this Broadway theater one night ÔÇö an usher was opening one of the doors, and I just slipped in and saw the finale of Sound of Music with Mary Martin. And I remember standing to see No Strings, with Diahann Carroll and Frank Sinatra.

Did you ultimately get to do Fly Blackbird in New York?

We played in L.A. over 11 months, a long run in Los Angeles. The rights were bought by an Off Broadway producer who said to us, ÔÇ£I canÔÇÖt promise you anything, but if you come to New York and audition, youÔÇÖll have a leg up.ÔÇØ The part was written for me ÔÇö the book writer was my playwriting professor, the character was named George, and I was the lone Asian-American college student in a group of predominantly African-American students. There was a comic number called ÔÇ£The Gong Song,ÔÇØ which talked about stereotypes from the Asian-American perspective. So more than a dozen of us auditioned, and only one of us was cast. And it wasnÔÇÖt me. We were devastated!

December goes by, and then January ÔÇö the most miserable time of the year to be devastated and depressed in New York! I loaded trucks in Long Island City, where you canÔÇÖt feel your hands because they get so cold; then another cast member got a job typing labels ÔÇö easier than loading trucks, but boring! And then the guy who did get cast left the show, and they needed someone immediately, so I came back near the end of the run.

My roommate had an aunt who catered very tony parties on the East Side, and occasionally sheÔÇÖd call and ask if we wanted to work at one of them.┬áThis was on the same day that I had gone to a mass audition for the part of an obsequious Asian servant with a comic laugh. I can do that, but IÔÇÖd promised my father I wouldnÔÇÖt. I walked out of that line. But that night, I had that black jacket and bow tie on, and I was indeed a servant, working that catered party on Sutton Place. But I rationalized it: My real work is that of an actor, and this is not my real work! I was accepting those fur coats and staggering up the stairs ÔÇö IÔÇÖm playing a part, this is only temporary. The irony still stings!

Are you a trained singer?

I was a theater student at UCLA, and one of the classes was musical theater, so yes. And I also sing in the shower.

You must be excited to be debuting on Broadway at a time when casts are finally becoming more diverse.

Now all these talented young Asian-American actors are getting great opportunities. We saw The King and I, and┬áHere Lies Love, and Ruthie Ann [Miles, who starred in both] won the Tony. At long last, weÔÇÖre getting the diversity of America reflected on Broadway stages ÔÇö I mean, Hamilton, telling the story of American history with the revolutionaries of our time, African-Americans and Latinos. And I suspect the actress with the last name, Soo ÔÇö her father must be Asian with that surname. And Allegiance is doing that as well. You know, I did Star Trek┬áÔǪ

Yes, IÔÇÖve heard that.

[Laughs.] And one of the prime directives was ÔÇ£infinite diversity in infinite combinationsÔÇØ ÔÇö which we turned into an acronym, IDIC. You saw that visually. The Starship Enterprise was a metaphor for the Starship Earth, this planetÔÇÖs diversity working in concert is its strength. WeÔÇÖre seeing Broadway now with that diversity.

You must have felt among kindred spirits on Star Trek, with other thespians like Shatner.

And Leonard! When I did Equus in Los Angeles at a small theater, Leonard [Nimoy], whoÔÇÖd played the part on Broadway, came to see it ÔÇö it was nerve-racking. He came backstage and I said, ÔÇ£Well, Leonard, howÔÇÖd I do?ÔÇØ And he smiled that very diplomatic smile of his and said, ÔÇ£You were better.ÔÇØ Which is preposterous!

Do you find thereÔÇÖs much crossover between Star Trek nerds and theater nerds?

Well, Star Trek night at Allegiance is October 31. Absolutely! TheyÔÇÖre going to come as Klingon warriors, Andorian princesses, or Starfleet officers. The theater will be filled with them! I intend to give the ÔÇ£live long and prosperÔÇØ salute at the curtain call, when we can break character.

Why are so many Star Trek stars ÔÇö you, Shatner, and Patrick Stewart ÔÇö so good at social media?

Well, thatÔÇÖs the future. WeÔÇÖve harnessed the technology of the future ÔÇö which is really not the future. Whatever seemed like science fiction back in the ÔÇÿ60s, we are living it today. We have this amazing device attached to our hip, no matter where we are, we can tear it open and start talking. In the ÔÇÿ60s, the idea of that was astounding ÔÇö no cords! WeÔÇÖre living in a science-fiction world. Star Trek was canceled in 1969, and right after we landed a man on the moon. For us, who were beaming to other planets all the time, a man landing on the moon seemed old-fashioned and clunky! The future is what we make of it.

*An earlier version of this article misstated gaman as nama.

*A version of this article appears in the November 2, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.