Last week a luminous secret tree fell in the visionary art forest ÔÇö that of the best UFO artist IÔÇÖve ever encountered. The artist was Ionel Talpazan (Yah-nell Tahl-pah-zon), who escaped Soviet Romania in 1974 at the age of 19, alone, swimming across the Danube River at night into Yugoslavia, where he was immediately placed in a refugee camp and then somehow was accepted in the United States as a ÔÇ£political refugee,ÔÇØ making his way to New York. He was an ingenious master of his subject and intricate systems. Most people never heard of him, however, because our crazy, beautiful art world persists in maintaining an apartheid system of ÔÇ£insiderÔÇØ and ÔÇ£outsiderÔÇØ artists where ÔÇ£outsidersÔÇØ are those thought to be weird, unschooled, and ÔÇ£obsessive.ÔÇØ Of course, hundreds of so-called ÔÇ£realÔÇØ artists fit this description to a T, but never mind. To this day museums, especially, balk at the thought of integrating these artists with the ÔÇ£realÔÇØ artists, as if the whole system would go to hell. Forget the market, which wants nothing to do with this stuff and sniffs at it as ÔÇ£the outsider market.ÔÇØ

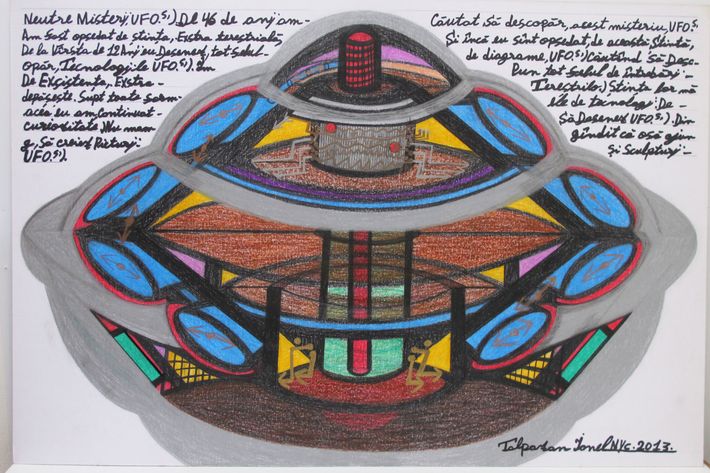

The subject and systems that┬áTalpazan mastered are all about an experience he says he had at 8 years old when he was abducted by aliens in Romania, brought aboard their spacecraft, and released. As with most abductees, he believes he may have been ÔÇ£probedÔÇØ as well. (Aliens have a real need for human semen and eggs, it seems ÔÇö the former especially.) Untrained but possessed by the experience, he spent the next decades of his life drawing this spacecraft, the cosmos as it was revealed to him, the planets, solar system, other worlds, while delving into systems of propulsion, mechanics, and electromagnetic forces; often color-coding works; and forever painting, drawing, and even making sculptures. I met him several times on the street where he sold his work. I always tried to buy something. Prices started high, often at $19,000. I would spend 45 minutes in whatever weather trying to bargain him down as he┬áalways┬áincrementally relinquished on the price until it got to a place where the figure hurt us both equally. That price was about $55 ÔÇö an amount that seemed like a lot to me and to him passed muster. I have never not lived with two of the six Talpazans I own; one is directly in front of my bed where I study its systems, geometry, internal structures, and incredible intervals of space.

Origin stories matter with artists like this who donÔÇÖt leave much of a paper trail and who will probably never get their due from the ÔÇ£realÔÇØ art world. My late friend Jay Tobler, a director at Barbara Gladstone Gallery, discovered Talpazan selling his work around Central Park one day in 1990. He saw instantly what many other similar spirits saw, too. Soon thereafter he wrote an article in a Virginia folk-art magazine. Somewhere between then and about 1995 I spotted Talpazan downtown for the first time ÔÇö I think at the corner of Broadway and Prince ÔÇö and was instantly smitten. As artist Carroll Dunham put it, ÔÇ£It was like seeing Henry Darger selling his work on the street.ÔÇØ Then another saint stepped in, a gallerist whoÔÇÖll never get his due either but whoÔÇÖs been doing great shows of so-called ÔÇ£outsidersÔÇØ for decades as well, Aarne Anton. Somehow he did the impossible and corralled Talpazan into mounting two shows in his Soho gallery in 1996. In 1996 Jeff Weinstein picked him for his┬áArtforum┬áÔÇ£top tenÔÇØ list; I wrote a couple of things, as did my wife, art critic Roberta Smith; Frieze Magazine did an article; and the┬áNew York Times┬áran a half-page article on him. The clouds seemed like they were parting. Other articles and mentions followed. Word spread, mostly among artists ÔÇö over and over that year I remember running into artists saying theyÔÇÖd seen ÔÇ£the best show in town,ÔÇØ and then hearing them mention Talpazan! I thought a miracle might happen and an outsider was going to make it over the insider wall.

But then Tobler died of cancer. Anton was only able to mount one more solo show. Then Talpazan more or less went on the lam again, reverting to selling his work on the street, living out of a tiny apartment ÔÇö I think in Harlem ÔÇö and working all the time. I kept up with him via word of mouth from fellow fans who spotted him selling his art on the street. During that time his work kept evolving, getting stronger, as he experimented with color, variances in scale, diagrammatic approaches, and topological structures. Each time I saw him I tried to cajole him to go back to Anton, but it was like I was speaking another language. HeÔÇÖd revert to talking about prices, recounting stories of what was going on in the drawings and paintings. Sadly, I never thought to record any of these amazing stories; I thought these lucky encounters would go on forever and reckoned that some alert curator had spotted him and would get the message out. Sadly, that never happened either.

A couple of years ago I spoke to Anton at the great Outsider Art Fair, which had been thankfully revamped and brought back to life by another hero of this quarantined world, Andrew Edlin. Anton told me that Talpazan was sick, very sick with some kind of circulation disease, and that he was probably dying, but┬ástill┬áworking and not consenting to show in galleries. Ionel had three great wishes. The first was that one day NASA would interpret his work as both science and art. The second was that when he is eventually discovered that he be known by the name he recently chose for himself: Adrian DaVinci. Those two things will hopefully happen one day. The last wish did come true. Not long ago Talpazan had ÔÇ£the happiest day of his lifeÔÇØ when he was sworn in as an American citizen. Among many other things, TalpazanÔÇÖs is a great immigrant story. I hope that some curious curator interested in Eastern European art might look into all this and make a small exhibition. I promise to donate all but two of my Talpazans to┬áany┬áNew York museum who gives him a shot. IÔÇÖll even waive the ÔÇ£$19,000.ÔÇØ