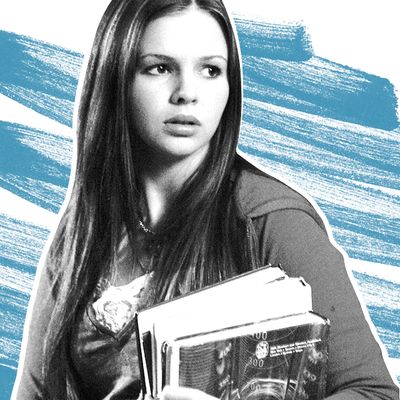

Joan of Arcadia ran for two seasons on CBS starting in 2003, in an era when networks were hanging on to the last gasps of dominance. It aired on Friday nights, opposite a sad pile of canceled sitcoms. The show was a tough sell: Teenage girl, played by Amber Tamblyn, talks to God, who appears to her in human form via various avatars. Maybe it sounds a little corny. Sometimes it actually was a little corny. But that’s an inevitable by-product when a show’s two main sensations are empathy and curiosity: How do any of us become ourselves? Plenty of series wonder that, but none with as open a heart as Joan. Some teen shows pity teen characters, or revel in their daily humiliations from the comforting distance of adulthood. Joan doesn’t see its teens all that differently from its adult characters: Identity is malleable, and everyone is trying to “figure things out,” frankly, with minimal success.

Despite widespread critical acclaim and an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Drama, CBS gave Joan the heave-ho when viewership declined in season two. Ten years on, it’s one of the most severely underappreciated shows of its time, and TV could really use another iteration.

A direct revival of Joan would be great — the show ended on a cliff-hanger, after all — but a general successor would be terrific, too. Family dramas don’t exist on network television these days: Jane the Virgin and Once Upon a Time are about as close as we get (RIP, Parenthood), and neither of those fit comfortably in the “family drama” genre, which generally, takes a focused look at one nuclear family. And one of the things that separates Joan from some of its more overtly wholesome, religiously themed brethren (say, 7th Heaven) is the lack of “type” for its main characters; they’re impressively fleshed out. Joan’s older brother Kevin had been a jock all-star, until he was paralyzed in a car accident. Even though the accident was not their fault, his parents’ guilt sometimes consumes their family. Younger brother Luke is smart and capable and completely ignored to a distressing degree because his parents tend to follow a squeaky-hinge model — Kevin and Joan make noise, while Luke quietly studies in his attic bedroom. Joan’s mom Helen is a rape survivor, and once in a while something triggers her, and she copes with reprocessing her trauma. Joan’s dad Will still carries a tremendous amount of resentment and abandonment anxiety because his own father left his family. That’s a pretty packed household — though not artificially so, and not condescendingly so. Did you know that all people have complex histories, and they’re doing the best they can, and sometimes it’s okay to just give people a break, especially the people you love?

Of course Joan’s calling card is that its star talks to God and God talks back, taking on the form of various people Joan encounters day-to-day: a janitor at her school, a little girl in the neighborhood, a goth kid she bumps into sometimes, and dozens of others. Mostly, God encourages Joan to be a good person, to stand up for things she believes in, to take social risks, to try new things — in general, Joan’s God is benevolent but vague, and not affiliated with any particular religious tradition. (“That’s what religions are: different ways to share the same truth,” God says at one point.) Shows rarely address themes and ideas about religion and religiosity, even though about 86 percent of Americans say they believe in God in some capacity. In the years since Joan went off the air, the American religious landscape has changed: Christianity is on the decline — down to 71 percent from 78 percent of American adults — and unaffiliation is on the rise. In 2007, 16 percent of Americans identified themselves as atheists, agnostics, or “nothing in particular.” In 2015, it was 23 percent. (Among those, “nothing in particular” — a group that still considers religion somewhat or very important in their lives — is the largest.) There are so many religious identities available: How might a young person trying to find her identity on a lot of fronts go about finding a religious or atheist ideology that feels true to her? What a good premise for a show!

Like other teens with superpowers — your Buffys, your Spider-Men — Joan’s able to use her extraordinary opportunities to tackle ordinary growing pains, and that’s what keeps the show from feeling preachy or morally superior. Adolescence is a time of big questions and big feelings and big choices. Joan’s erratic extracurricular schedule was often at God’s behest, but there’s nothing unusual about a teenager whose parents are sometimes surprised by their interests, or a teen who surprises herself with an interest (going from “I’ve never heard of that band” to “I am the world’s leading expert in that band” is a normal part of teenagehood). Incredibly tight bonds form incredibly quickly, and suddenly, someone whom you were never friends with is the be-all, end-all of cool. Somehow, Joan’s interactions with the divine don’t seem that outside the realm of normal teen behavior.

Joan’s biggest success, and the part of the show that ought to be replicated more across all television, is how seriously it took all its characters and their ideas about what was reasonable and right. Joan learns how to combat apathy, ignorance, and NIMBYism. That’s a rich set of lessons, ones adults are often relearning. A show in which smart, compassionate people can disagree in nuanced ways, in which there are many different ways to be a person, is a lot more interesting than a show where everyone teams up against the very obvious big bad guy. We have shows that grapple with global politics, the debased nature of mankind, the impermanence of romance, the dangerous allures of success. And that’s great, truly. Yet somehow Joan of Arcadia is one of vanishingly few shows to bring up two extremely common questions that shape the human condition: “Is there a God?” and “Am I a good person?” The answer to both is, it depends whom you ask. And you can only ask so many people in two seasons.