Steven Soderbergh is in motion. It’s a warm day in Greenpoint, and the 52-year-old director, cinematographer, editor, and executive producer of Cinemax’s late-Victorian-era hospital drama The Knick is on the show’s main set, camera in hand, circling a table in a surgical theater, blocking a scene in which a patient’s gallbladder is removed. Soderbergh speaks softly. The cast and crew hang on every word. Then he starts shooting. He is moving, pausing, repositioning the actors, and moving some more. Technicians and writers gather just out of camera range, staring at an iPad that’s patched into Soderbergh’s camera via wireless, as the scene is sculpted and refined in real time. If you watch the screen, you can see aesthetic questions being asked and answered by the shifting positions of the actors in relation to Soderbergh’s lens. What is the point of this scene, this shot, this camera movement? Where is the best place to begin? On André Holland, who plays Algernon Edwards, the hospital’s acting chief of surgery? Or on Clive Owen, who plays Edwards’s onetime boss, the brilliant surgeon, medical inventor, and self-destructive opium addict John W. “Thack” Thackery? Perhaps the first shot should both start and end with a close-up of medical instruments used in the procedure? Would that be repetitious? Okay, maybe the shot should end farther away from the actors, and then the next shot should pick up in close-up? Ah, yes, there we go, that worked. Much better. With its elaborately choreographed and composed long shots, this is the kind of scene that might take three hours to complete on network hospital dramas and even longer on Hollywood movies. Soderbergh knocks it out in less than two.

His direction of The Knick is unusual in pretty much every imaginable way, but let’s start with the fact that it’s all his: Soderbergh helmed the entirety of the show’s first ten-episode season, which aired late last year, and did the same for season two, which premieres on October 16. For all of its visual evolution in recent decades, TV is still a writer-producer’s medium where series directors rotate in and out as needed, rarely overseeing more than two or three episodes in a row. Occasionally one person might direct eight back-to-back episodes of a limited-run project like The Honorable Woman (Hugo Blick) or True Detective’s first season (Cary Joji Fukunaga). And once in a great while you’ll see the majority of a long-running series directed by a single person, as with Louie (Louis C.K.) — but rarely on a show with as many moving parts as The Knick, and in such a punishingly tight time frame. Soderbergh has now directed 20 hours of a lavish costume drama at the speed of a run-and-gun indie film: Both seasons wrapped, according to The Knick co-creator and co-writer Jack Amiel, in about 150 days, “which is less time than a lot of crews would spend shooting one big movie.” The Knick shoots eight to nine script pages a day, double the typical rate for a TV drama, and burns through an hour-long episode in just seven days, versus the industry norm of ten to 14.

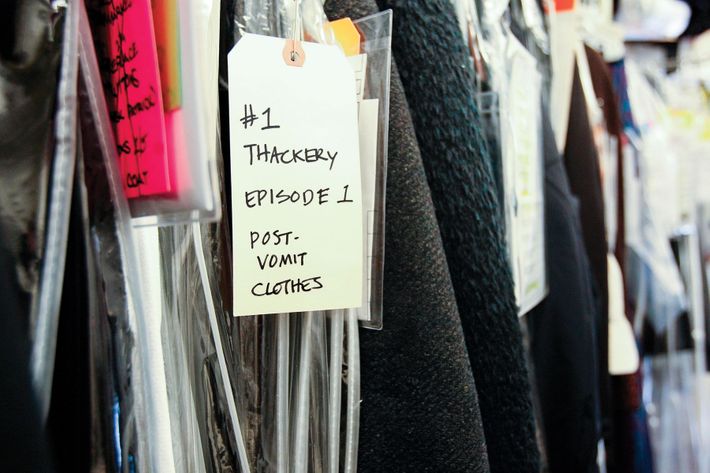

The Knick’s second season opens with a good portion of the main cast scattered to the winds: Thack has been ousted as chief of surgery for his drug use and is feeding his addiction by performing facial reconstructions on syphilis victims; the former nun Sister Harriet (Cara Seymour) has been kicked out of the order for facilitating abortions; hospital-board member Cornelia Robertson (Juliet Rylance) is in San Francisco agitating against the quarantine of Chinese-Americans during a bubonic-plague epidemic. The first couple of new episodes maneuver them back into the Knickerbocker Hospital and set the season’s plot in motion, mixing in more signifiers of the city’s ongoing evolution toward modernity, such as the replacement of the hospital’s horse-drawn carriage with “horseless” ones and the increased prominence of electric lightbulbs.

The show’s style is different, too. More so than in season one, scenes in season two often consist of long, sinuous camera moves and a few tight close-ups. Sometimes, during a scene with long monologues, Soderbergh will focus on the face of a single listening character and not cut away. “There are moments when you don’t think it’s your scene, but it is,” says Eve Hewson, who plays ER nurse Lucy Elkins, Thackery’s lover. The Knick can look more like a John Ford or William Wyler or Orson Welles movie, in which every image is carefully considered, than most modern scripted TV, where the goal is mainly to capture performances and push the story along. Soderbergh mentions Welles’s The Trial and Chimes at Midnight, in particular, as influences on the look of season two, with their “sustained shots that go on forever.” “It’s kind of like the arcade game with the water-filled tube and the ball,” he says during a lunch that lasts exactly 18 and a half minutes. “How long can I keep this shot interesting, dynamic, and narratively appropriate to what’s going on, given the elements that I want to emphasize?”

Soderbergh shoots with a handheld camera, sometimes while being pushed by grips on a small, wheeled platform that he calls a “dolly du derrière.” This allows him to participate in scenes as an equal with his actors, rather than being “50 feet away, behind the monitor,” he says. “I like the intimacy of that, and I think the actors like knowing how close I am.” Watching him direct is akin to witnessing an athletic performance. Soderbergh walks, jogs, runs, sits, lies on the floor, and hangs half off dollies while PAs grip his ankles. “When I tell other cameramen what goes on with Steven, they’re flabbergasted,” says Soderbergh’s longtime second cameraman, Patrick O’Brien, who works on only about 30 percent of The Knick — usually when Soderbergh needs him to gather extra close-ups in a scene with a lot of characters, operate a crane that he’s sitting on, or shoot the other side of a two-person conversation. “He’s like a dancer,” says Holland. “One time, on the first season, it was bitter winter and we were shooting outside, and he was in this awkward, crouched-down position, holding the camera and moving at the same time, and midway through the take, his knee gave out and he jumped up and winced in pain. You could hear a pin drop, because you know that his physicality is such a huge part of the show.”

Everything and everyone on set is enabling Soderbergh’s endurance test. An assistant cameraperson shifts focus via remote control from another room, freeing Soderbergh to concentrate on movement and framing. The Knick’s standing sets are lit with visible (or “practical”) lights — desk lamps, chandeliers, and so forth — to let Soderbergh and his actors move anywhere they want and still get a lovely image. Everyone knows that they have to be as politely relentless and focused as their boss. There are no stand-ins on the set of The Knick, no Gulfstream trailers for producers and cast, and no canvas chairs, because no one sits still long enough to require them. A workday here is a nine-to-six sprint, with an hour off for lunch. “Actors love working with this guy,” O’Brien says, “because they’re not sitting around all day waiting for the set to be lit.” Soderbergh tells me: “It keeps the actors on the boil, nobody leaves, and — like we just did — you can power through the whole scene and it’s done.”

Soderbergh’s preferred digital camera, the Red Epic Dragon, also helps. Its low-light capacity has let him shoot handsomely composed scenes, starkly illuminated by a naked lightbulb, a gas lamp, even a match — cinematographic flourishes in the spirit of one of his favorite movies, Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 drama Barry Lyndon, the first feature to shoot scenes by candlelight. At one point during our conversation, Soderbergh digs his cell phone out of his pocket and calls up a two-minute tracking shot from season two in which Cornelia Robertson moves “through a house with a candle and we follow her, and that’s it. Just one candle, and you can see everything!” he says, marveling at the flickering image on his phone.

Most directors would not get handed a handsome period drama to treat as their own personal train set, but that’s because they don’t have Soderbergh’s track record of making stylish, innovative, occasionally commercial art cheap and fast and without much fuss. Since his 1989 debut, the Cannes Palme d’Or winner sex, lies and videotape, he has directed 25 features (including the four-and-a-half-hour, two-part biopic Che) plus nearly 30 hours of TV (including the 2003 HBO political satire K Street, each episode of which was plotted, scripted, shot, cut, and broadcast in five days). He is one of the few American directors to claim two Oscar nominations for Best Picture during a single calendar year, for 2000’s Erin Brockovich and Traffic; he won Best Director for the latter. Every one of his movies — including the comparatively glossy heist thrillers Ocean’s Eleven, Twelve, and Thirteen — was produced for what is, by contemporary American studio standards, chump change.

And he is endlessly, perhaps helplessly, prolific. In 2010, he told his friend Matt Damon that he was “retiring” from making theatrical features because he felt he’d exhausted the medium — a statement that was widely misinterpreted to mean that Soderbergh was quitting the business entirely and that launched a thousand jokes along the lines of “In the time it took you to read this tweet about Soderbergh’s retirement, he directed a remake of Berlin Alexanderplatz.” Right now he’s got The Knick; a show in the works at HBO with Sharon Stone; and an executive-producer credit on Amazon’s new Red Oaks, a circa-1985 period drama directed by David Gordon Green (Pineapple Express). He’s fascinated by long-form storytelling, which he says is “very different” from features and offers more possibilities for experimentation, because TV’s aesthetic hasn’t been developed as deeply as cinema’s. Whole seasons of The Knick are written before a frame is shot, and any subsequent revisions are about in-the-moment problem solving. “Having all ten scripts beforehand allows me to sort of think on a macro level for longer, and that’s good for me,” he says.

Soderbergh thinks like an editor while he’s shooting, never wasting anyone’s time on anything he thinks he might not use. “Steven doesn’t cover the same thing 19 times,” says Amiel. “He’s going to do it once and know that’ll be his first half of the scene and we’re not going to shoot it again. [For] the second half of the scene, he may shoot three or four pieces of coverage, but it’s because he’s already cut the whole scene in his head. He already knows.” “Often the shot that ends up in the show is the first one that we got,” says Holland. “Early on he said to me, ‘I don’t see any reason why we need to make things any more complicated than they have to be.’ ”

At 6 p.m. each day, Soderbergh climbs into the backseat of a van and starts cutting the day’s footage on a laptop on the way home from the set. He finishes by eight, posts the results on a password-protected website, and goes to dinner, a play, or a movie with his wife, Jules Asner. “People on the crew will say, ‘I can’t wait to see what we did today,’ ” says production designer Howard Cummings. Changes in technology have allowed Soderbergh to become imaginatively fused to his digital cameras, laptop, smartphone, and the internet. “I have to show this to you; I can probably pull it up on my phone,” Soderbergh says, hunting through footage folders on The Knick’s postproduction website and calling up an acrobatic long take that follows actors through a fund-raising ball. “If I had this shit at the beginning of my career,” he says as the phone screen fills up with costumed extras, “the movies would’ve been a lot better.”

*This article appears in the October 5, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.