R. Kelly whirls around, straining to look out his car’s rear window. “You see that?” asks the R&B star, sitting in the middle row of a black SUV cruising down Manhattan’s West Side. On this sparkling afternoon in early fall, he’s just noticed a young woman driving a red sedan one lane over. “Damn,” says Kelly, as the smoke from his cigar curls along his giant gold watch and up past his diamond earring. “Uhm-hmm,” says a bearded assistant in a baseball cap from the backseat. This man’s job, as best I can tell, is to light his boss’s cigar and carry around a small duffel bag. The SUV pulls even with the woman’s car, and Kelly, on his way to a Chelsea recording studio, goes quiet, staring at the woman as she looks straight ahead.

Our driver changes lanes. Kelly grimaces, as if seeing an attractive woman in a passing car and not being able to do anything about it hurts. “New York got a lotta pretty girls,” he says. His assistant gives a sleepy nod.

The SUV pulls in front of the studio. We’re here to listen to tracks from next month’s The Buffet, the 13th album of Kelly’s massively successful, extremely controversial career, and the first one since allegations of his past sexual misconduct resurfaced online, causing many to argue that Kelly is both a predator overdue for punishment and a walking moral dilemma.

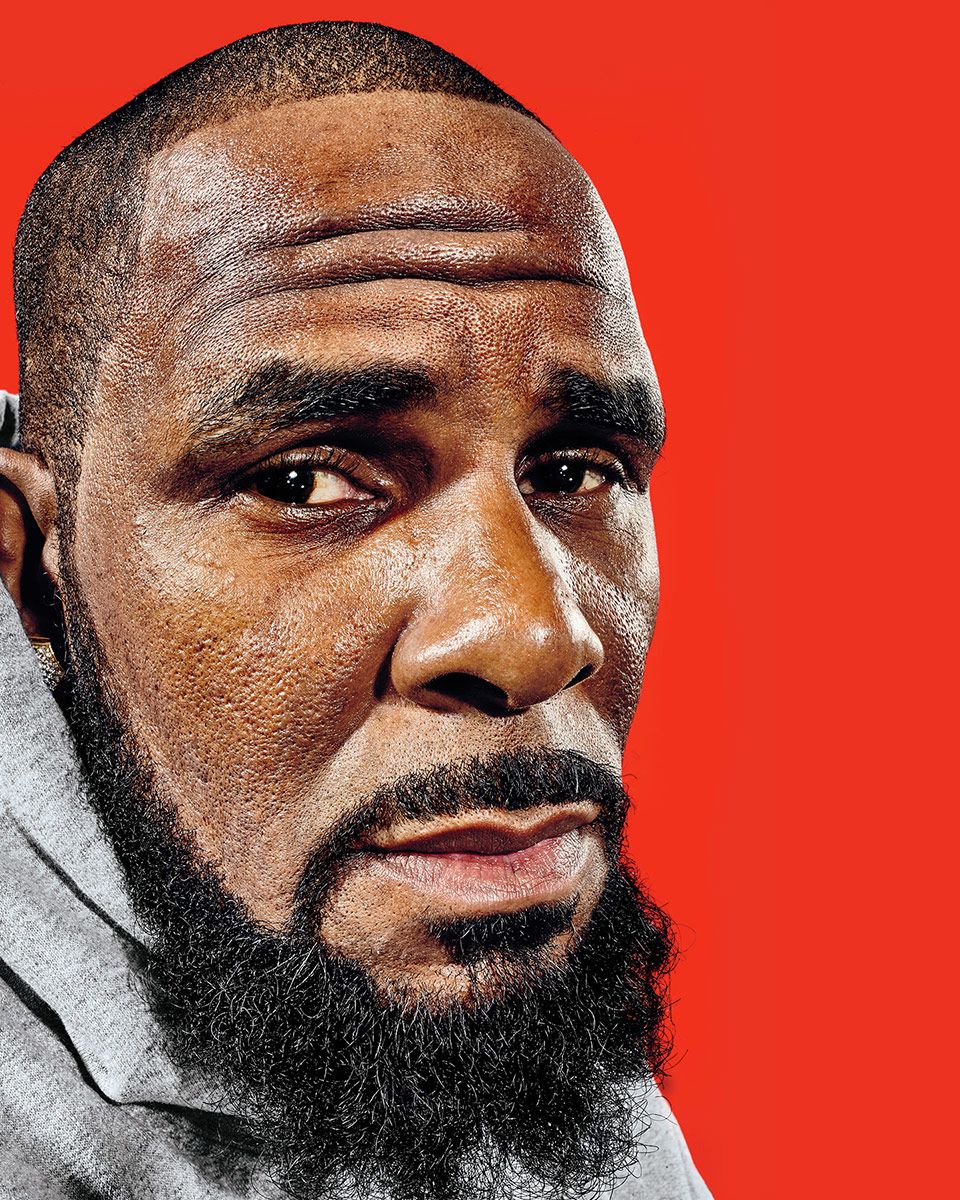

We step into an elevator. As it rises, Kelly, tall and wearing patterned jeans, sunglasses, and a baggy gray hoodie that mostly hides his slight middle-aged paunch, points his cigar at me. “You gonna be asking me all these things,” he says. “So let me ask you something first: What do you call a black man who flies an airplane?”

I don’t know.

“You call him a pilot,” says Kelly. “What’s wrong with you?” He laughs. “Gotta keep you off balance,” he says. “Gotta set the tone.”

So let’s do that. Here are some key things to know about R. Kelly. His first name is Robert, he’s 48 years old, and he’s inarguably the biggest male R&B singer since Marvin Gaye. Probably the most talented and sexually explicit, too. He grew up poor and functionally illiterate — owing to dyslexia — on Chicago’s South Side, raised mostly by his mother. In his memoir, Soulacoaster: The Diary of Me, he wrote about being sexually abused as a child by a woman from the neighborhood. Around the same time, boarders in his family’s house repeatedly made him take photos of them having sex. When he was 8, he watched helplessly as his first love, Lulu, drowned after bullies pushed her into a creek. At 11, he was shot by thieves trying to steal his bike. The bullet is still in his shoulder.

Kelly was musical from as far back as he can remember, and he began his career on the streets, singing for money in his clear, gorgeous tenor. In 1991, he joined a New Jack Swing group, Public Announcement, and went solo soon after. His debut, 12 Play (as opposed, the logic goes, to a less capable lover’s foreplay), was released in 1993. Since then, Kelly has sold somewhere in the neighborhood of 34 million albums. He’s been nominated for 25 Grammy Awards and won three. In 2010, Billboardnamed Kelly the No. 1 R&B and hip-hop artist of the last quarter-century. In addition to his own batch of 33 sinuous, perfectly arranged top-20 R&B hit singles, and another 17 that achieved the same designation on the pop “Hot 100,” Kelly has collaborated on smashes with Céline Dion and Michael Jackson. Pitchfork deemed his irresistible “Ignition (Remix)” the 19th-best track of the aughts. He was largely responsible for introducing Aaliyah, Drake’s emotional lodestar, to the world. Even Jim DeRogatis, the former Chicago Sun-Times reporter and pop critic, who has done more than anyone else to spread the word on Kelly’s alleged unlawful sexual behavior, admits: “The man is a musical genius.”

That’s the music. There’s also this: a long list of allegations that Kelly has used his money and power to have sex with minors. In 1994, when Kelly was 27 and Aaliyah was 15, the two were married under a falsified document that stated she was 18. The marriage was quickly annulled and Kelly, who produced Aaliyah’s debut album — called Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number — hasn’t said much about it since, out of, he says, respect for the late singer’s family. (Aaliyah had signed an agreement requiring her to stay silent about the brief marriage.) In 1996, Kelly was sued for damages by a woman alleging the two began a sexual relationship when she was 15. Kelly settled out of court. In 2001, a similar lawsuit with a similar result. The next year, he was indicted on 21 counts of making child pornography after police came into possession of a video depicting a man resembling Kelly having sex with a young woman. Also in 2002, another lawsuit, this one from a woman claiming both that Kelly impregnated her while she was underage and that one of his associates took her to get an abortion. Kelly settled. That same year, a woman sued Kelly for filming, without her knowledge, the two having sex. Kelly settled. It goes on: at least a half-dozen more lawsuits, followed by settlements, followed by nondisclosure agreements. (There are also reportedly a handful of instances in which Kelly has agreed to payments before lawsuits were even filed. Presumably these, too, involve NDAs.)

Also in 2002, a video, delivered anonymously to DeRogatis’s mailbox, showed a man who looks an awful lot like R. Kelly having sex with a girl alleged to have been about 14 or 15 years old at the time. In the video, which was widely bootlegged, the man is seen urinating in the girl’s mouth. It took prosecutors six years to bring the case to trial. The girl in question refused to testify, and Kelly’s lawyers argued that, as in the 2006 comedy Little Man, in which CGI was used to transpose Marlon Wayans’s head onto a child actor’s body, someone could have faked the tape by digitally replacing another man’s face with Kelly’s. He was acquitted on all charges.

Despite all the allegations — and DeRogatis puts the total number of lawsuits in the dozens — Kelly has never gone to trial for, or even been charged with, statutory rape. Why not? Chicago attorney Susan E. Loggans, who won settlements for multiple Kelly accusers, explains that for the state to prosecute a statutory-rape charge, there needs to be a complaining witness, and there hasn’t been one. “People don’t trust the legal system,” she says. “Everybody wants to see if they can get out of it. You can be on the right side of a case and lose, and that’s devastating. It’s easier to be provided with money and not go through the trauma or risk of a trial.”

And yet. Kelly’s former manager Barry Hankerson once wrote a letter to Kelly’s lawyer in which he said their client needed to get help for his sexual compulsion toward underage girls. The husband of Kelly’s former publicist Regina Daniels told Los Angeles radio station KJLH that Kelly had “crossed a line” with the couple’s daughter. Kelly’s brother, Carey, told radio host Wendy Williams that he was asked to collect phone numbers of girls in the audience at R. Kelly shows even though “they looked underage.” Kelly’s former friend and personal assistant Demetrius Smith wrote a memoir, The Man Behind the Man, in which he wrote: “Underage girls had proven to be [Kelly’s] weakness. He was obsessed. Sickly addicted.”

For a brief period after his acquittal, Kelly, musically anyway, appeared cowed. Love Letter (2010) and Write Me Back (2012) were both chaste compared with most of his hits and musically humble, homages to classic soul. Divorce was presumably humbling, too. He and his wife, Andrea, who’d publicly supported her husband, divorced in 2009 after 13 years of marriage. The couple has a son, Robert; a daughter, Joann; and a third child, Jay, born Jaya, who announced last year on social media that he’s transitioning from female to male. “He’s a, I dunno what the name of it is,” Kelly tells me. “You love your kids no matter what.”

But in 2013, Kelly let loose. He duetted with Lady Gaga on her racy, unrepentant hit “Do What U Want,” and the two gave a truly bizarre performance at the American Music Awards in which he played the president and she played a secretary dry-humping in the Oval Office. Then he released his own volcanically dirty Black Panties album, featuring songs like “Crazy Sex” and “Marry the Pussy.” The record was like a dare to the world: After all that he’d been accused of, after avoiding conviction, could R. Kelly still get away with making sex-obsessed music?

At the Chelsea studio, Kelly is seated at a desk behind the recording console, a track list and keyboard in front of him. He takes small drags from his cigar. His assistant, a publicist, and a manager sit shoulder-to-shoulder-to-shoulder on a nearby couch. Kelly, who speaks softly and rarely looks my way when he responds to my questions, asks an engineer to cue up a track from the excellent The Buffet — one of 462 songs Kelly says he wrote for the album (13 made the final cut). “I have enough songs to put out six or seven albums a year if I wanted,” he says while fiddling with the track list. Despite his superhuman output, quality control is not a problem, he says, because “feedback comes to me through the people who work for me.” He admits that on a couple occasions, he’s been told that songs were duds, but he can’t recall which ones because “I’m so buried in all of the great songs that I’ve been fortunate to have out there.” (Kelly is playfully exaggerative on a broad number of topics: An avid pickup-basketball player, he tells me that his jump shot is accurate “to about half-court, so that I don’t have to drive to the hole and worry that someone hits my pretty face.”) The Buffet, Kelly says, has a little something for all of his fans — hence the title — and he “really does believe my music will play until Jesus comes back.”

The engineer clicks a mouse, and Kelly’s insistently seductive voice fills the room. “My lyrics got a big dick / And I just fucked the shit out of you all.” Kelly looks at me, tilts his head, and puts his hands out in Whaddaya think? fashion.

Most of Kelly’s music falls into one of two categories: wholesome, inspirational songs about salvation and God, and filthy ones about freaky sex that often employ imaginatively silly metaphors — cooking (“In the Kitchen”), mountain climbing (“Echo”), space exploration (“Sex Planet”) — for the act of coitus. But the latter outweighs the former by a wide margin: For every “Heaven, I Need a Hug,” a handful of “I Like the Crotch on You,” and a heap of “Feelin’ on Yo’ Booty” for every dash of “U Saved Me.” He doesn’t release the clean stuff under one name and the dirty stuff under another, the way some artists might. It’s all part of the same complicated persona, and each part of his catalogue informs the other: Listen to enough dirty songs, and a totally clean one like “It’s Your Birthday,” for example, might trick you into anticipating a punch line that never comes. (He brought a birthday gift for you, but it’s not his penis, surprisingly.) There’s also Kelly’s 33-parts-and-counting rap opera Trapped in the Closet — whose narrative follows Kelly’s character, Sylvester, through a twisted series of events involving cuckolding, a surly dwarf, and a stuttering pimp — which exists in its own wondrous category.

The music on The Buffet doesn’t much resemble the tenser, more emotionally conflicted songs of current R&B hit-makers like the Weeknd, Frank Ocean, or Miguel — all of whom have, let’s say, a more subdued vision of how two people might interact with the lights down low. Kelly isn’t ultrakeen on his younger competition. “R&B should be making love,” he says, stroking his freshly trimmed beard. “It should be sex with a little comical feeling; all that shit when you macking to a girl so you can get with her.” In other words, R&B is exactly what The Buffet sounds like. Kelly performs beside me as the songs play — cuing imaginary musicians, pumping his fist, mouthing the lyrics, raising his hands to the heavens. When we get to a sex song that uses a marching band as a metaphor, Kelly sings, “Blow me like a tuba!” and does it with such aplomb that I can’t help but laugh, and he smiles, and it’s awkward. Because this moment makes plain the conundrum of R. Kelly: How do you — how do I — listen to his songs, these ingeniously produced, meticulously arranged, incredibly sung songs, after you know what he’s been accused of?

“I don’t think about what people say R. Kelly did do or he didn’t do,” says Charisse, a 38-year-old EMT in a red leather jacket. We’re standing outside Barclays Center in Brooklyn in late September. R. Kelly is playing here tonight, and in a few minutes he’ll deliver a lewd and wildly entertaining show. “He don’t do anything lots of other men don’t do,” Charisse continues. “But because it’s R. Kelly, I’m supposed to be mad about it? There’s a lot of fast girls out there looking for a come-up.” She shrugs. “That’s reality.”

Tia, 34 and pregnant, is here too. She works in wealth management, and her husband is home with their young daughter. “The media overhypes everything,” she says. “If he was found guilty in court, that’s a different thing. But there’s life and there’s music, and I can separate the two.” Her husband can’t. “He refuses to listen to R. Kelly,” she says.

A 40-something man who’s been listening in and who won’t give his name comes up to me and says, “Innocent until proven guilty. This is America,” and walks away.

Kenny is a 33-year-old real-estate agent whose girlfriend bought him R. Kelly tickets for his birthday. He was unaware of any allegations. “I’ve never heard any of that stuff,” he says. “So I guess it doesn’t bother me.”

Of course, R. Kelly has heard that stuff, though at the studio he answers my questions only in roundabout ways. “I’m going to always have the gift along with the curse,” he says, after we’ve finished listening to his album. “I feel like I got a million people hating me, I’ve got maybe 8 million loving me. So I’ve got 9 million talking about me, and in a strange, magical way, it keeps me in the game.”

In 2014, Slate asked, “Why Does Alleged Sexual Predator R. Kelly Still Have a Career?” The year before, the Village Voice ran a conversation with DeRogatis in which he recapped, in wrenching detail, the allegations against Kelly. Online, the piece linked to nearly ten years’ worth of disturbing Sun-Times stories and police reports.

“Why haven’t we reached a Cosby-style tipping point with him?” asks DeRogatis from his office at Chicago’s Columbia College, where he teaches cultural criticism. “R. Kelly had the good sense never to go after a white girl from Winnetka. He didn’t go after Janice Dickinson. He was [allegedly] targeting inner-city black girls. The white world, with some exceptions, did not give a fuck. Certainly not in the way they did about Cosby, who was an actual crossover artist.”

R. Kelly is, of course, not the first popular musician to allegedly be turned on by minors. Elvis began courting Priscilla Beaulieu when she was 14. Jerry Lee Lewis married his 13-year-old second cousin. Marvin Gaye impregnated a 16-year-old. But none of them did so under the watchful eyes of the internet and social media. Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page never had to discuss having a 14-year-old girlfriend during his band’s bacchanalian heyday. Kelly, the scope of whose alleged behavior is far beyond that of the aforementioned musicians, had an #askRKelly Twitter Q&A in 2013 that quickly turned disastrous. (Sample question: “On a scale of 1 to 10, how old is your girlfriend?”) His reckoning keeps on rolling but at seemingly no tangible harm to his career.

As best I can tell, many of R. Kelly’s fans don’t care about his alleged past, insofar as they’re even aware of it. And even if they do have some ambivalence, they can stream “Ignition (Remix)” on, say, Spotify, and enjoy Kelly’s music without worrying about putting much money in his pocket. So what, then, is someone like DeRogatis looking for? How should we hear R. Kelly? “People need to be aware of, given the subject matter of his art, what he is really about,” DeRogatis says. “You can despise the individual and appreciate the art, fine, but you need to be aware that you’re making a conscious decision to overlook some very, very bad behavior. You’re either ignorant of what he’s been charged of, or you’ve thought it through and said, ‘That all matters less to me than his cool grooves.’ What I want is for people to at least think about it.”

Kelly isn’t overly concerned with what people think. “You never know who they gonna get next,” he says nonchalantly when I ask if he feels hounded by the press. “I haven’t heard anything negative about me in I don’t know how damn long.” His assistant, who’s fallen asleep on the couch, jerks awake and asks permission to go for a smoke, clutching the duffel bag as he gets up. Kelly makes him relight his cigar first and says, “I choose my circle and keep all the squares out.” I ask if he thinks the media misrepresents him, and he gives a typically oblique answer. “If I take a Tylenol right now in your face, and you don’t know what it is, you might start wondering, am I popping pills? Next I’ll be hearing, ‘I saw him popping pills, he on that shit, girl!’ ” Throughout our conversation, the multiple phones Kelly keeps in the pocket of his hoodie vibrate every few minutes. “Who the fuck,” he mutters incredulously during one FaceTime call with a woman, “goes to bed wearing makeup?” When his assistant returns, trailed by a bodyguard carrying platters of shrimp, Kelly immediately digs in. It’s good, but not as good as his favorite. “The McRib,” he says dreamily. “I have people tell me when McDonald’s is offering its limited-time-only menu so I can get one.” Moved by his reminiscence, he starts humming “Mac Tonight,” a jingle set to the tune of “Mack the Knife” from a late-’80s McDonald’s commercial. “Shit,” he says, “I should remix that.” Before he can, he pivots to address a frequent criticism. “People say my lyrics are offensive,” he says. “If that’s offensive, then movies about babies getting snatched up and people getting shot in the head should be called offensive. It’s all entertainment.” He turns to the engineer and says, “Play ‘Sex Time.’ ”

Kelly swears that he’s not intentionally tweaking listeners by releasing music that evokes his alleged real-life deviance. He’s just giving people what they want. Or, as he puts it, “When someone orders a sausage-and-cheese pizza, you don’t give them pepperoni. When their mouths are fixed for some R. Kelly, they want the freaky stuff.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said that the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at once. That, for example, a horrible person might make a wonderful song. That John Lennon, who expressed regret for being “a hitter” in his early relationships, can also be responsible for a song as beautiful as “If I Fell,” or that whatever Michael Jackson did or did not do with underage boys doesn’t turn “Human Nature” into a lie. Songs are better than people. And R. Kelly, in a weird way, through his sex obsession, makes that truth most obvious. The fact that his career hasn’t cratered, despite all the damning allegations, makes it clear that when people are listening to music, they’re not thinking about how powerful men often take terrible advantage of less powerful women. Or about how those men are surrounded by enablers for as long as they remain bankable. Or how the media is not responsive enough when troubling things happen to young black women. Or how legal settlements and NDAs are effective tools for suppressing damaging information. Or that part of the fun for some listeners is in how far a singer might be willing to go, lawyers and good taste be damned. Or how looking for rectitude from coddled celebrities is like looking for rainbows under rocks. Or how at the other end of our quotidian consumer pleasures is often another human being’s pain. So the answer to the question “How do you listen to songs by a singer who may be a bad person?” is devastatingly simple and sad. You just do.

The next time I speak to R. Kelly is a week or so after the Buffetlistening session. I call a recording studio in California at seven in the morning West Coast time. A publicist puts him on the phone.

Do you have a sexual attraction to underage girls? I ask.

“That’s a rumor that comes from the Earth, like all rumors,” he says, sounding almost bored.

So it’s not true?

“No. It’s not true. I love women, period. If I wasn’t a celebrity, people wouldn’t be saying these things about me.”

How do you explain people close to you saying that you have a problem?

“I don’t know those people you’re talking about.”

I clarify: his brother, his ex-publicist, his former friend and longtime personal assistant.

“All those people have been fired by me. If you’re going to ask me these questions, you have to make sense out of it. It wasn’t until after they got fired that they said these things. Go figure. I got one life, and I don’t want to spend it talking about negativity. I’ve moved on. Maybe you haven’t.”

It’s not crazy to think that where there’s smoke there’s fire.

“Let’s correct that,” he says. “Smoke can be anything. I’ve seen smoke and then I looked and there was no fire.”

And what about all the settlements? All the rumors?

“I understand the game,” Kelly says. “Get as much dirt as you can on somebody, get it all together, and make it real juicy so we can sell some papers. I understand the job you guys have to do.”

How do you explain the tape that Jim DeRogatis got?

“I don’t have no recollection of none of that. My lawyers handled that, what, eight, nine years ago?”

Do you have a sexual compulsion or problem that you need help with?

“I only have a problem with haters. Other than that, I’m doing well. I feel better than ever with my album The Buffet.”

In your career, you’ve often sung about forgiveness. What do you need to be forgiven for?

“I go to church. I ask for forgiveness. Don’t make a big deal out of R. Kelly saying it in a song. I believe in God. I fear God. I don’t want to go to hell.”

Do you think you might?

“Young fella,” he says, “absolutely.”

*This article appears in the November 16, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.