Carter Burwell’s tenure as a Hollywood composer is a bit remarkable, both in terms of longevity and adaptability. As the go-to composer for the Coen Brothers and Spike Jonze, Burwell has readied scores for more than 80 films, ranging from bloody dramas (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) to dark cult comedies (The Big Lebowski, Being John Malkovich) to youth-aimed blockbusters (Twilight, Where the Wild Things Are). And that’s exactly how he likes it. “I love the opportunity to do something that I haven’t done before,” he explains. “If someone comes to me with the opportunity to do something new, either with the instrumentation or with the whole concept of the film, that is always attractive. The least interesting thing is when people are asking you to do something that you’ve already done. Then I don’t really see the point.”

With a handful of films he scored out this past year — most recently, Carol and Anomalisa — Vulture called Burwell at his studio in New York last week to discuss the stories and inspirations behind seven of some of his most well-known scores.

True Grit (2010)

For the Oscar-nominated remake of the Western classic, the Coen Brothers met with Burwell well in advance of filming to plot out their musical strategy. “The first thing they said was, ‘We don’t want to do Western music.’ And I felt the same way,” he says. “In a way, their other films had old-timey country music, like in O Brother, Where Art Thou? Even in Raising Arizona, we did our own version of Western music. That approach just wasn’t an interest to any of us.” To prepare, Burwell read the original 1960s novel by Charles Portis, which proved to be very fruitful for finding inspiration.

“Comparing the two, the one thing that was in the book that didn’t come through in the script is the inner voice of the girl [Mattie Ross, played by Hailee Steinfeld]. She’s the author of the book, so her perspective is there constantly, and it’s written in an intriguingly humorous way because she’s so hard on everyone else in the world, and she believes in her own righteousness,” he says. “It’s also clear in the book that it comes from her church sermon. She’s constantly referencing the Bible, but it’s not so present in the movie. So we wanted to bring some of that churchiness to the movie. It would help explain why she’s behaving the way she is, and why she’s daring enough to go out in the wilderness after these outlaws.”

Burwell pitched the church angle to the Coens, who were very receptive of the idea. “I think Ethan had a similar thought, too,” he says. “So while they were shooting the film, I was going through 19th-century hymn books, trying to collect hymns from that period that would suit the story. They couldn’t be comforting hymns, it had to be tough, like the girl. Would it be choir or organ? How churchy did we want it? After a couple of attempts, we realized we were pushing that point too hard. So we decided piano was the best instrument, largely because it feels churchy but it doesn’t force you into thinking about church. You can think of it in other ways.” The backbone for the score was born.

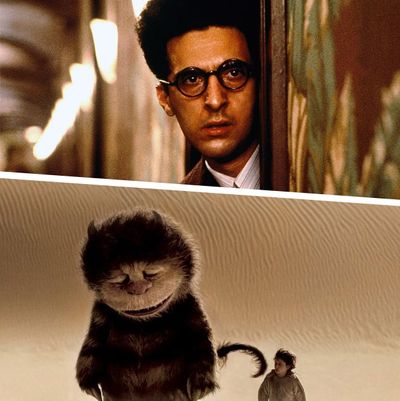

Where the Wild Things Are (2009)

“When Spike [Jonze] went to shoot the film, he called me beforehand to say he didn’t think he was going to engage me as a composer, because he wanted it just to be songs, and Karen O [of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs] was going to write those songs,” Burwell says. As Jonze began editing his adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s beloved children’s book, he realized that some of the story elements couldn’t be told just through songs. “It needed more in certain areas, something different. Even years after I worked on it, I still can’t explain why and how some areas are best served for song and best served for instrumental score, but it just became clear that was the case,” he says. “So it ended up being half Karen and half me, and there’s some overlap. I did some instrumental work on Karen’s songs, and she did some vocal work on my pieces.”

Burwell used his score to ground protagonist Max’s fantastical mind in emotional reality. “In something like Being John Malkovich, making that world real is a bit more of a challenge. But for Where the Wild Things Are, I think everybody wants to believe in this place, they’re pining for that,” he says. “My goal was living in Max’s mind and always being aware of the things that got him to this point — why he’s there, why he ran away from home, what are the issues he has, and how that’s going to all be a motivation for him returning home. That was the path that was very important for me to convey, because some people originally weren’t getting it.”

Twilight; The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part 1; The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part 2 (2008, 2011, 2012)

When Burwell began working on the firstTwilight movie, Stephenie Meyers’s vampire-romance series had yet to grip the masses it would once its five-part film franchise arrived, but that’s not to say there wasn’t still some pressure from the diehards. “It was a very modestly budgeted teen romance,” he says. “There was also a period in the development of the film that the blogosphere became used as a word, and it was the first time I was aware of the blogosphere, because they’re actually reading a lot of what the fanbase had to say about the books, and what they were anticipating from the movie.” This included the main tune from Twilight (“Bella’s Lullaby”), and how its corresponding (and key) scene in the book would translate onto film. “There’s a scene in the book where Edward plays it for her, but there’s nothing that tells you what kind of a tune it is,” Burwell says. “So all of the millions of people who read the book had in their own minds an idea of what ‘Bella’s Lullaby’ would be.”

But the studio originally did not plan to incorporate that scene into the film, as it was deemed not relevant enough to “advance the story.” “But while I was working on it, they decided, ‘Well, we have to have “Bella’s Lullaby,” all of these people on the internet are asking what “Bella’s Lullaby” is going to sound like in the movie.’ So that fell into my lap,” he says with a laugh. “You could just see that there were literally millions of people who already had their own ideas about ‘Bella’s Lullaby,’ and some had already put their own versions on YouTube. While the movie was being made, other musicians were contributing their own ideas for ‘Bella’s Lullaby.’ There was a bit of pressure from that, but because we didn’t know it was going to be a box-office hit at the time, I was saved from having to think about that at all.”

When he worked on the final two films, parts one and two of Breaking Dawn, it was a different situation. “It was really trying to satisfy the fans and somehow tie up this package of all of the films,” he says. “By the last one, the music and the film references all of the films before, and tries to make it a completely satisfying end to a cultural phenomenon.”

No Country for Old Men (2007)

When you think of No Country for Old Men, the Oscar-winning neo-Western thriller from the Coens, you might recall that there is barely any score. This is intentional, of course, but difficult to appropriately execute, absolutely. “It was primarily Ethan who doubted that there would be a score that would be better than no score, which is one way to put it. Joel entertained the idea that there could be a score for this movie, and we just have to figure out what it is,” Burwell says. “I was in between, where I wanted to do a score for the film, but it’s true that everything I tried … every time you heard something that identified as music would diminish the tension. And the movie is all tension, and once you diminish the tension, it’s like letting the air out of a balloon.”

In the end, Burwell came up with a solution to use sounds that didn’t inherently sound like a “score,” sneaking them in as sound effects. “You never actually hear the score appear, so it can’t have the effect of pulling you out of this quiet, frightening reality of the film. It always sneaks in,” he says. “Sometimes it’ll disappear quickly, and that’s maybe when you notice it.” He specifically mentions the infamous scene where Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) does a coin-toss as a prime example of how that operates.

“The life of the man who owns the service station is in the balance, and when the coin is revealed, the music stops,” he continues. “And suddenly you realize, ‘Oh, I guess there was music there, or something just changed, I don’t know what it is.’ But you never actually hear music enter the scene, which was our solution of how to allow music to intensify the drama while still making sure that you’re really not aware of its presence at all.”

Being John Malkovich (1999)

“When I first read the script, I told Spike [Jonze] there was nothing about the script that dictates what music it should be,” Burwell says of the dark comedy, which blurs the line between fiction and reality by casting Malkovich as a distorted version of himself. “It could be literally anything. Because it has these fantastical elements and a wild story, as Charlie [Kaufman] wanted, he follows the story farther then you possibly can think you can. He follows the premise to the very end with complete commitment.”

Jazz, funk, and “Fellini-esque” sounds were brought up at various points during the early production stages. “In the end, we found the most interesting challenge from this would be to make it seem like these are real people and that real things were happening,” he says. “Like if you really believed you could go into someone else’s brain or that you could have other people in your brain — because that would be the most disturbing possible interpretation of the film — and we should try to achieve that with the music. So the music totally ignores all of the fantastical parts going on, completely. Instead, it plays the often melancholy reality of the characters.”

Fargo (1996)

“It’s one of those times when the music and the story and the characters and the writing and the acting all come together perfectly to make something unique,” Burwell says of the Coens’ most celebrated movie. “I like scores where there’s some grand concept. For Fargo, there was a concept. Joel and Ethan had said, ‘Okay, we think the problem for this film is going to be how do you make people believe that the violence is real, but also get people to laugh at it?’ They wanted people to somewhat believe that it’s a true-crime drama. They do want you to believe that people are actually getting hurt and dying, but the people who are doing the violence are also the buffoons in the story, and you can laugh at that.”

The Coens thought capturing that dissonance would be “the primary challenge,” so they tasked Burwell with finding a signature sound that would remain constant throughout the film. “My proposal was that the music would never hint at the comedy that’s intended, but it would also be overly serious,” he says. “Taking itself too seriously would then lean back into comedy by being a little bit too bombastic. I used film-noir types of orchestration and built it up.” The other concept that came to him was using Scandinavian instrumentation. “There’s this folk fiddle in Norway and Sweden called the Hardanger fiddle, which we used on an old Scandinavian folk tune called ‘The Lost Sheep,’ expanding it for the main theme,” he continues. “Because of the names of the characters and the white landscape that you’re seeing, I thought that maybe there would be something about it that would work, and fortunately, it did.”

Burwell says he was approached for the acclaimed television adaptation of Fargo, but he wasn’t interested in scoring it. “Someone did ask my agent if I was interested,” he says. “I couldn’t do a regular episodic television thing. It couldn’t maintain my interest for that long, and it couldn’t work with my schedule, anyway. So, no, I wasn’t interested. I did tell them they were certainly free as far as I was concerned to use the music from the film.”

Barton Fink (1991)

Like No Country for Old Men, the original score ideas for Barton Fink were very minimal — mostly the intensification of background sounds to play up the film’s threatening and mysterious aspects — but that progressed into something more substantial that focused on Barton’s character. “Originally Joel was dubious that there would be any score in that movie,” Burwell says. “Their original idea was that most of the film’s score would be played by sound effects. If you watch the film and pay attention to the sound effects, it’s certainly true. The sounds of the hotel that Barton Fink is living in is scoring a lot of what’s going on. But I had this idea that there was one thing in the story that wasn’t going to be stated as sound effects, and that’s Barton’s childlike qualities. Although he considers himself to be a man of the world and living the life of the mind, he in fact knows nothing about the world. I had this very high piano tune that I played for Joel and Ethan, and they got it. The main idea was to do something that would speak to the fact that Barton is in fact a child and completely naïve.”