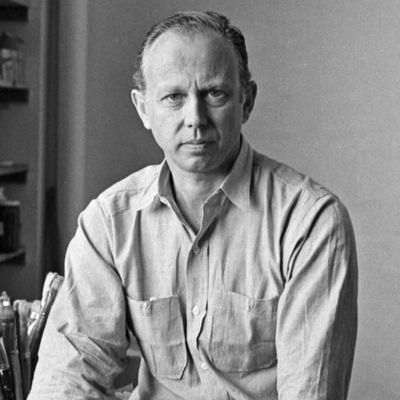

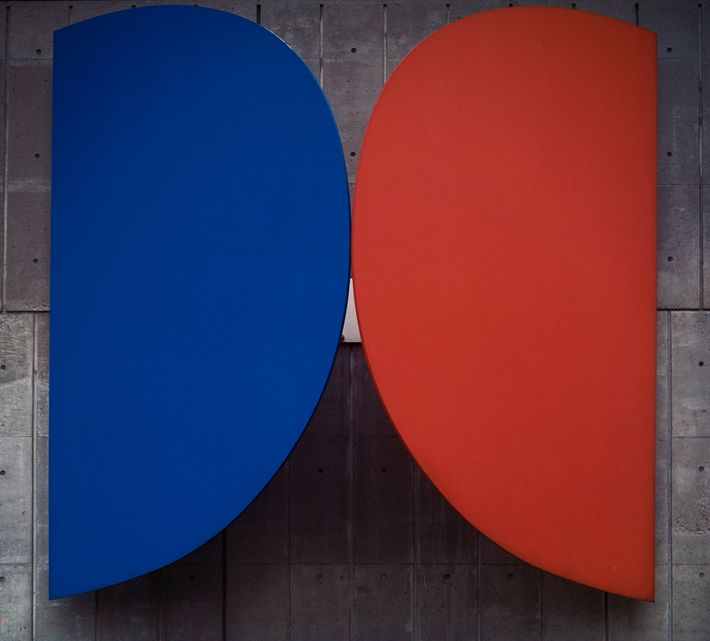

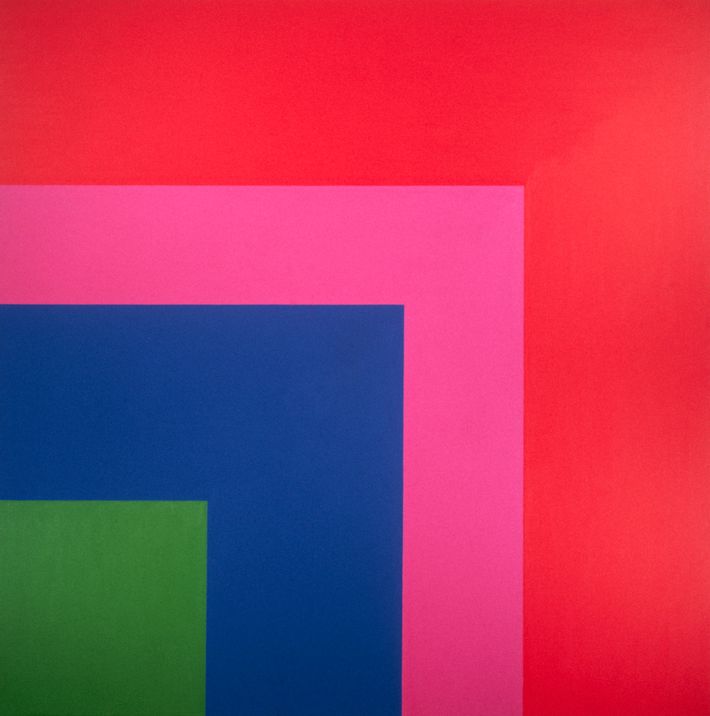

A small confession: I came to appreciate the paintings of Ellsworth Kelly, the artist I now think of as the American Matisse, in only the last ten or 15 years. Now, his work stuns me from its own Platonic eternity. I see one of his paintings, and I wake from my habitual self and feel like I’m in the presence of some shimmering undead vampire, something incessantly present. But, for 20 years or more before that, I respected his work but thought it just too simple, too similar, a static happiness not a bubbling one, just Minimalism. All that shifted in the months after September 11, 2001, when I was in a museum and happened to start staring at a Kelly. Maybe it was the need in me after 9/11 to be able to believe in art again, but suddenly I allowed this incredibly simple, elegant, nonrepresentational, melodious thing to come to life. Maybe I finally got out of my own way. Maybe I accepted hot-coldness, cool-heat. Either way, few paintings now ever seem as fresh, as if in an eternal state of right now — form making meaning, color obsessing and overtaking us — emanating in waves off surfaces as plain-simple as any in art history, no words to describe them, save simple ones like “square” or “curving” or “flat.”

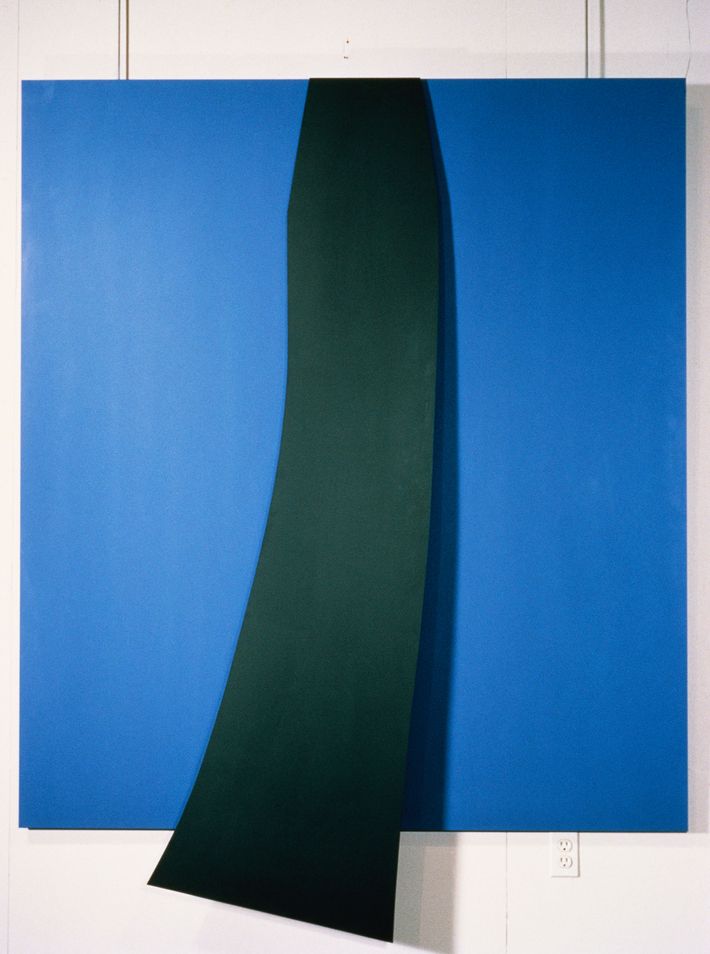

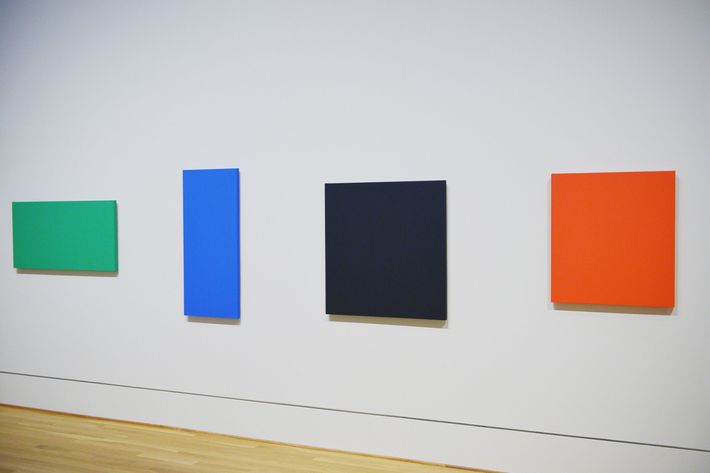

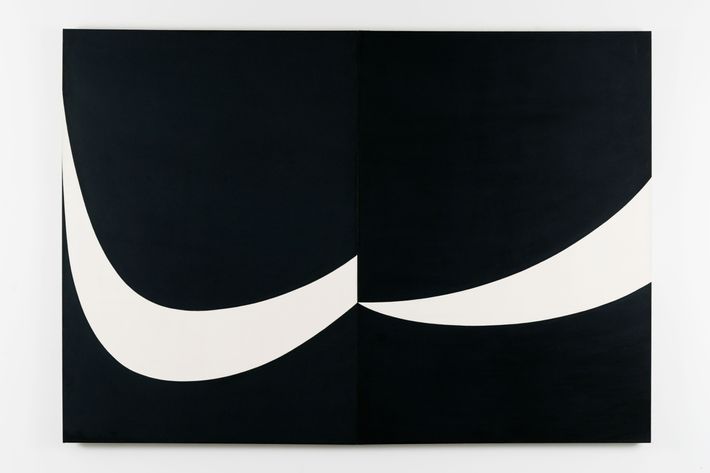

This is the work of Ellsworth Kelly, whose shaped, monochrome, opaque, hard-edged, stacked, and incandescently optical paintings have since the early 1950s — when, nearing the height of Abstract Expressionism in America, the young New York native, fresh from military service and the G.I. Bill and living in Paris — took a bold jolting turn into a new kind of geometric abstraction: minimal paintings that came as much from the facets of Cubism, Constructivism, and Mondrian as they did from Americans like Stuart Davies, Burgoyne Diller, and the young John Cage and Merce Cunningham, whom Kelly met in the French capital. Kelly distilled all this into a proto Pop-Op visual aliveness. Even when Kelly’s work can seem repetitious, you can feel it extending your ideas of how shape, space, color, and place interact with and alter one another in real time, affecting perception, stopping you in your tracks at how much imaginative grandeur something this simple can contain. Each time I hear myself beginning to think, Oh this again, I follow the fervor of immersion into ardors of color, listen to my eyes telling me, Look at this! See how he gets this pointy edge to seem to have been painted in 15 different shades of gray when it’s only shadow and flat white!

Kelly’s Minimalism, such as it is, isn’t doctrinaire, reasonable, on-message. Instead his huge shaped canvases cohere in more subjective space where the mind and eye play with forms, creating larger circles — systems that might not make sense — forming arcing edges or extended long slopping lines into exotic configurations that feel very much part of the world, almost architectural. Kelly’s work exists at some metaphysical-visual junction where we are in immediate contact with the medium of painting itself — its formal characteristics and uncertainties — morphologies of shape, overexposed light, mathematics, form and fragments, power, and the emancipatory openness of the eye. He gives permission to just love color, prettiness, the miracle of chromatic intensities — for themselves and the sensations that seem inherent, internal, part of form itself. It’s hard to overstate just how radical this prettiness is when it comes to modernism and the ways it often comes with backstory, theory, rationale. Kelly makes us revel in something as simple as a large monochrome floating painting and see it not only as a crack into meaning, but also as something that has attained an almost inviolate foreverness. Not one of his works ever seems old to me. Instead I see enclosed Edens; cosmic geometry.