Like its high-end true-crime brethren, Netflix’s new ten-episode Making a Murderer is gripping, a little salacious, and about more than its central legal saga — in this case, rural poverty and entrenched power structures. The show fits right in with The Jinx and “Serial,” and it’s at least as good as both, and maybe better in some areas. But The Jinx is much more of a spectacle, and “Serial” is much more of a mystery series. Making a Murderer is an anthem of hopelessness. It’s as engrossing as they come, impactful and devastating, and it left me with a hollowed-out despondence generally treatable only with alcohol and ranting.

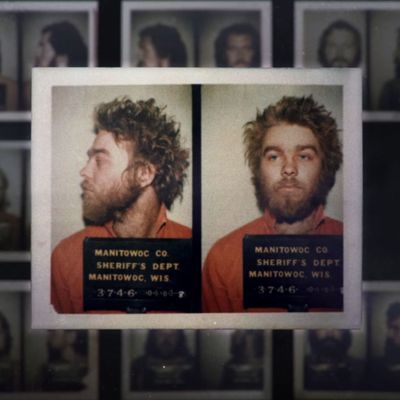

Making a Murderer centers on Steven Avery, of Manitowoc County, Wisconsin. He was wrongfully convicted of sexual assault in 1985 and spent 18 years in prison before a DNA test finally exonerated him. Two years later, Avery was arrested again — this time for the murder of Teresa Halbach, a photographer and business acquaintance. Avery’s defense attorneys make a compelling case that Avery’s the target of a police conspiracy, and the prosecution relies heavily on the confession of one of Avery’s nephews, then 16 years old. That confession, which was videotaped, is one of the most haunting segments I’ve ever seen, and not because of how disturbing the material within it is, although it is disturbing. Mostly it’s upsetting because of how staggeringly, appallingly coerced it seems. Something horrible clearly happened — a woman was killed, her body dismembered and burned. But justice that comes from coercion and corruption isn’t justice.

Like “Serial,” Making a Murderer is, for better or worse, hardly about its victim at all; in both cases, the victims’ families declined to participate. Repeatedly in the show, we see clips of Halbach’s brother saying he and his family believe the prosecution’s theory of the crime, which adds an additional layer of heartache into the story. There’s so much agony here, so much loss and confusion. There are also several different perspectives playing out: On obvious levels, Making asks us to consider the roles of investigators, prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, juries. Witnesses. News media. It also forces us to think about the roles of documentarians, and what our role is as an audience member. I don’t believe the prosecution’s theory of the crime, and I don’t know if that obligates me to do more than simply carry that knowledge. I already knew wrongful convictions existed. I already knew that confessions could be coerced. Simply bearing witness to the story feels like a cop-out, but the show isn’t (and shouldn’t be) a specific call to action. I don’t know what happens after documentary like this, the kind of social response we should aspire to. Making captures and engenders the tension between wanting to run into the streets and scream — who could hear these wails and do nothing? — and knowing that louder people already did and their cries went unheard, or worse, were heard and ignored.

There were a few moments in Making a Murderer that sent me reeling, but perhaps none more than one of the prosecutors telling the jury, “Reasonable doubt is for innocent people.” That’s a common thread in the show, a feeling of, wait, that can’t be right … can it?, an overall sense of frustration. Filmmakers Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi superbly combine the legal system’s uniquely high stakes with its ordinary tedium and boring bureaucracies. Frustrating ineptitudes and prejudices reign within our criminal-justice processes, just as they do everywhere else on our planet. Let’s note here that Steven Avery is white, Teresa Halbach was white, Avery’s nephew Brendan Dassey is white, all the police officers and judges and lawyers are white. Many, many stories about the American justice system are stories about race. This one is a story about class, unambiguously. It’s about other things, too, but this show doesn’t exist without profound, pernicious in-group/out-group class conflict, one that posits that the Avery clan can never be fully innocent because they’re already guilty of the greatest crime in America: being poor.

I didn’t enjoy Making a Murderer — enjoy makes it sound more pleasant than it really was — I was engulfed, and also crushed, by it. I lied about plans so I could rush home and watch more episodes, though mainlining a show this distressing is not a great way to live. I encourage you to resist the urge just to Google everything about the case until you’ve watched the whole series. Bring friends with you on this voyage, too. It’s a harrowing but worthy trip.