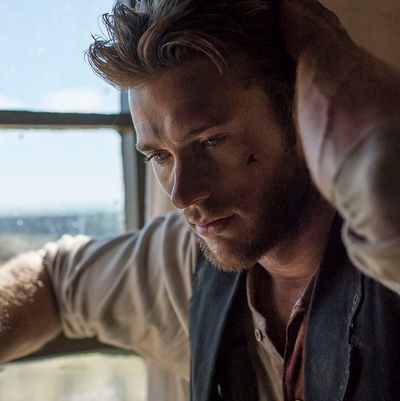

There are a couple of moments — instances, really, lasting just a second or two — when Scott Eastwood briefly becomes a dead ringer for his father Clint in the new Western Diablo. The angle has to be right, the lighting has to be right, and the glower has to be right. It doesn’t happen often. The son has a much softer, less distinct face than the father; he’s very good looking, but blandly so. And yet, every once in a while, something goes wrong, and there’s Clint.

I mention this because Diablo, an interesting but uneven Western directed by Lawrence Roeck, tries to get at a kind of inner lunacy in Scott Eastwood — an inner Clint, let’s say. And for the most part, I’m not sure it’s there. Or at the very least it’s buried very, very deep — too deep for this film to access when it needs to. Eastwood plays Jackson, a man whose wife we see being kidnapped by what appears to be a Mexican gang in the film’s opening scene. The next day, he sets on his way to track down the kidnappers. Along the way, he finds himself running into a dapper, black-clad, vaguely demonic figure named Ezra (played by our modern cowboy everyman Walton Goggins), who playfully goads and taunts him.

For much of its running time, Diablo presents us with the surfaces of a traditional Western — beautiful vistas, a lone man riding out in search of a lost woman, occasional run-ins with other characters who inhabit this rough land, a sense of civilization having been left behind. It does so in such a predictable manner that one suspects it’s trying to lull us into thinking we’ve been transported back to an era when people still made such movies. But it also becomes clear about halfway through that something is purposefully amiss in this story. Something that happened during the Civil War haunts Jackson. Ghostly apparitions show up. Goggins’s character keeps coming back in odd ways, and we realize he’s either imaginary, or supernatural. By the time the film works up to its finale, what secrets it wants to reveal to us have become fairly obvious. But they still carry a dark charge; Diablo’s ultimate grisliness is impressive in its own way.

And it might have worked, had the film not asked entirely too much of its young lead. In the performances he’s given so far, the younger Eastwood has had a pleasant but shallow aura around him. Dad was handsome, gaunt, and deadly; he seemed to have an endless inner reserve of meanness. The son is pretty, buff, and unassuming. In last year’s Nicholas Sparks adaptation The Longest Ride, he made for an engaging rodeo champ, the one member of the film’s multi-generational love quadrangle who wasn’t brooding, or emotionally broken. That film, while not very good, knew what to do with him. And as evidenced in those brief, aforementioned moments in Diablo when a little evil peeks through, there may very well be something more there. Director Roeck uses Eastwood’s bland likability; the plot requires that Jackson seem like an ordinary decent guy to the people he encounters. But there’s a lot more to the story, and so far this young actor hasn’t displayed the kind of range or inner conflict required to pull off a part like this one. And without a strong lead to hold it all together, Diablo falls apart.