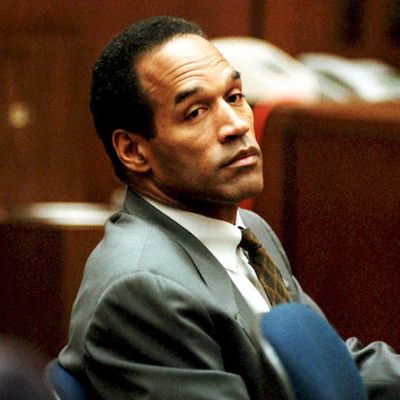

In the annals of unreliability, there has never been a narrator less reliable than the I who governs the text of If I Did It. In fiction, an unreliable narrator is the product of an author’s design, a persona behind whose words the reader has to glimpse a deliberately obscured fictional state of things. In the case of O.J. Simpson’s 2007 memoir, we have instead an unstable mix of variously cynical narrative forces that combined to produce what was briefly a best seller and what is now a lost exact opposite of a classic.

It is, perhaps, the most notorious publishing story of the 21st century, sleazy enough to make the safe-deposit-box caper that gave us Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman read like Nancy Drew. The prime mover in the saga of If I Did It — the farcical middle chapter in the trilogy bookended by the tragic murder of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman, and the pure pulp finale of O.J.’s incarceration for armed robbery and kidnapping in Las Vegas — was Judith Regan, then the powerhouse of her own imprint within HarperCollins. Regan was a trusted lieutenant of Rupert Murdoch’s — if not a News Corp capo at the level of Rebekah Brooks, then one still claiming a similar level of intramural villainy in the media biz. (If you’ve stopped keeping track, Regan, the former producer of Geraldo and lover of ex-con ex–police commissioner Bernie Kerik, is now the publisher of Regan Arts, an ideologically and aesthetically slippery imprint within the otherwise tasteful L.A.-based art house Phaidon.)

Regan signed up O.J.’s conditional memoir with an advance said to be somewhere between $600,000 and just north of $1 million, with the money said to be going to a trust for his two children with Nicole. Regan enlisted Pablo F. Fenjves, a former colleague from their late-1970s stint at the National Enquirer and a witness at the Simpson murder trial (a neighbor of Nicole’s, he testified against O.J. about how he had heard Nicole’s dog barking that night). (Fenjves says he didn’t like the tabloid game, and left it for straight journalism, ghostwriting, and screenwriting; among his credits is the 1995 film The Affair, which happened to star Courtney B. Vance.) Fenjves and O.J. sat together for two days to go over the easy stuff, right up to the night of the murder, and O.J. enjoyed it. But the next day he was “restless and angry” and had “trouble focusing.” He complained: “You know what kills me? All the goddamn people who assumed I was guilty before they heard my side.” “I’m sorry,” Fenjves tells him, “I thought you were guilty then, and I still think you’re guilty.” O.J. says, “I know you do, motherfucker!” But then his good humor returned, he thanked the ghostwriter for being honest, and they set about the tricky work of writing the infamous chapter six, O.J. insisting all the way that he was describing a “hypothetical” set of occurrences as he provided details that Fenjves thinks he couldn’t have invented simply because they’re too banal to make up. Did Nicole’s dog Kato (I had forgotten that Kato) wag his tail at Goldman and O.J., or just Goldman?

Somebody leaked news of the book to the National Enquirer. (Fenjves thinks it was Regan herself.) News Corp. was widely denounced, not least for the slimy synergy of its plan to put O.J. on Fox News for an interview with Regan herself. (Barbara Walters and ABC had passed.) Murdoch stepped in and canceled what he called an “ill-considered project,” and then he canned Regan. (It was reported that the cause was that she’d told a co-worker that a Jewish cabal within News Corp. was out to get her; she would sue and win a settlement in excess of $10 million.) It came out that the trust safeguarding the advance for Nicole and O.J.’s children was under O.J.’s control. Regan claimed she’d done it all to expiate her own abuse at the hands of men and “with Ron and Nicole in my heart.” “I wanted him to confess his sins, do penance, and to amend his life. Amen.” Touché. A Florida bankruptcy court awarded the rights to the Goldman family, to go some way toward what they were owed for the civil decision against O.J. in Ron’s wrongful death. They tacked on the subtitle Confessions of the Killer and published the book in the fall of 2007, without O.J.’s name or image on the cover but just in time for his indictment in Nevada. (Their edition was tricked out with a prologue by Fenjves and an afterword by Dominick Dunne; the paperback adds a tedious legal apparatus of the Goldman-Brown family feud, among other matters.)

As for the text itself, given the conditional nature of the title, if we were to believe it and accept it without irony, it would seem that O.J. did it because he heard some rather vague rumors about his ex-wife’s behavior. In chapter six, these rumors are delivered by Charlie, a fictional character proposed by Simpson and deployed by Fenjves. Charlie is a guy O.J. recently met at dinner with mutual friends and later did some clubbing with. “I liked Charlie — he was one of those guys who is always in a good mood, always laughing — and I told him what I tell a lot of people: Stop by when you’re in the neighborhood. I guess he took it literally.” Charlie shows up on the fateful night at O.J.’s door just after O.J. and Kato Kaelin go to McDonald’s for a burger that isn’t going down too well. (Recall Marcia Clark to Kaelin on the stand: “Are you sure you did not go to Burger King?”) His good mood has been disturbed at a dinner he was attending with some fellows unaware of his (fictional) friendship with O.J. They were telling bawdy tales of one weekend in Cabo and an encounter with Nicole and her friend Faye. In Charlie’s retelling: “There was a lot of drugs and a lot of drinking, and apparently things got pretty kinky.” O.J. replies: “Why are you fucking telling me this, man?” Indeed.

The actual murder scene, hypothetical or not, is no masterpiece of storytelling. Those who’ve tracked the account against the evidence presented at the trial think that, Charlie’s presence aside, most of it lines up. Telling Charlie, “We’re going to scare the shit out that girl,” O.J. approached Nicole’s condo through its broken back gate. He saw candles flickering inside and heard faint music playing. Then Ron Goldman, a waiter who was returning Nicole’s mother’s glasses from his restaurant Mezzaluna, where they had dined that evening (O.J. had been invited), also entered through the back gate. O.J. took Goldman for one of Nicole’s friends in cocaine and kink, or perhaps one of Faye’s “boy-toys,” and a shouting match began. O.J. says “motherfucker” a lot. Charlie shows up, wielding the “limited edition” he kept under the driver’s seat of his Bronco for dealing with “crazies.” Charlie is one moment the devil on O.J.’s shoulder, fanning his rage, the next moment the angel, at one point wisely counseling him, “Let’s get the fuck out of here, O.J.” Nicole appears and pleads, reasonably, that she can do what she wants in her own house. “Not in front of my kids, you can’t!” O.J. accuses Goldman of being a drug dealer. Nicole rushes at him “like a banshee,” trips, knocks her head on the stoop, and seems to be unconscious until she starts moaning. Goldman adopts a karate stance, bobbing and weaving. Charlie attempts to insert himself between O.J. and Goldman, but O.J. snatches the knife from him. At the climax of the encounter, O.J. blacks out, then wakes up standing in the same place, covered in blood, as if his own patsy. O.J. and Charlie make a getaway and return O.J. to his house in time for him to make it into a limo to go to the airport. Charlie disposes of the murder weapon and O.J.’s bloody clothes, and O.J. flies to Chicago for a meeting with Hertz.

O.J. said he wanted to spare his children any details of how their mother’s throat was cut nearly to the point of decapitation: Thus, the blackout. But he gushes through the self-serving 130-page account of the unraveling of his marriage, and that precedes chapter six. Poor O.J. Amid his endless rounds of celebrity golf, pregame shows with Bob Costas, the occasional turn as Norbert to Leslie Neilsen’s Frank Dreblin in the Naked Gun movies, his sole aggravation seems to be Nicole’s wishy-washy behavior, her halfhearted attempts at reconciliation, her psychobabble about finding herself, her dodgy friends and occasionally inappropriate outfits, her dalliances, including the one she decided to tell him about with her friend Marcus Allen. He spends a lot of time venting that he only ever laid a hand on Nicole once, that time he pushed her out of the bedroom while she was throwing a temper tantrum and she called the cops on him in 1989. (Oh, then there was the night in 1984 when he took a baseball bat to the tetherball tied to the tree, and then, finding that an insufficient anger outlet, bashed up her Mercedes.) There are lots of trips to Vegas and Cabo and New York. When Nicole doesn’t want him around for Thanksgiving after their separation, O.J. goes to Detroit to call a Lions game for NBC. One night, when she has a date over at hers, he stops by, peeps at their living-room-couch make-out session, and, to spook them, rings the front doorbell and then drives away. It would all make for a pretty mild episode of Melrose Place if nobody had gotten killed. After chapter six, the text weirdly reverts to innocence mode, and O.J. and Fenjves get sloppier with the details in their version of the low-speed chase in the Bronco, an event so public that the text’s omissions and deviations from the record indicate something like malpractice. Perhaps it’s another case of O.J. blacking out. He was that day suicidal, supposedly, until he heard Dan Rather talking about him on the radio.

During the publishing debacle, Regan told the press the idea for the book had been given to her by a friend who was ex-CIA, who told her that criminals like to confess in the form of hypotheticals. A review of the book in The American Spectator compared O.J.’s conjuring of Charlie to James Earl Ray’s confession to Congress that he was accompanied by a man named Raul, who apparently didn’t exist, when he killed Martin Luther King Jr. Whether or not he did it, why do we want to think about it again? Do we? The book’s first public reader, James Wolcott, found that returning to the ballad of O.J. and Nicole just made him want everyone once again to go away. But alas, they’re back on TV. This time we know how it ends, so it’ll be easier to turn them off.