When I first heard that the Guggenheim was doing a big show of my favorite collaborative artistic duo ever, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, I fretted that it might be too late for a retrospective of these artists who came to prominence and have been beloved by the art world for more than 40 years. Since the 1970s, this Swiss duo crossed the unusual materials and processes of post-minimalism with a squirrelly spirit of inquiry via fanciful metaphysical experiments and arrived at their own astylistic blend of sculpture, photography, and video. They were spanners in the works of art ÔÇö philosophical phenomenologists in pursuit of what they called ÔÇ£the pleasure of misuse.ÔÇØ (Too bad we donÔÇÖt use the word pleasure┬ámuch anymore when talking about art.) I feared the proceedings would turn sad, with Weiss recently deceased; that the work might come off as one long, wacky ÔÇ£what we did on our summer vacationÔÇØ romp, or it would just seem like another slick show of male artists.

I was way wrong.

The tipping incline of the Guggenheim ramp turns out to be the perfect place to highlight the divine instability of the great art of these masters of recalibration, imbalance, trial and error, eclecticism, doubt, looking for success in failure, asking unexpected questions, and of arriving at waggish answers like Illuminati alchemists of modern life. This deep content resonates wonderfully in the GuggenheimÔÇÖs majestic exhibition. The timing of the show, called ÔÇ£How to Work Better,ÔÇØ is more auspicious still. In this strange moment when so many young artists, strapped with debt, seem spooked by art-school strictures and whatÔÇÖs ÔÇ£permissible,ÔÇØ many have become ultra-self-conscious, almost crippled over how they ÔÇ£brand,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£commodify,ÔÇØ and present themselves. The way Fischli and Weiss let art unspool, following process and materials to logical and illogical ends, never bothering to make sense or have elaborate external backstories, could set a lot of artists free.

Start with the 30-minute The Way Things Go. Not only is it the best art video IÔÇÖve ever seen (this from someone whoÔÇÖs watched Matthew BarneyÔÇÖs Cremaster 4 and Pipilotti RistÔÇÖs Sip My Ocean over 75 times), it could have won the Best Picture Oscar in 1987. (The year of the okay Platoon.) A masterpiece of unnamed genre, itÔÇÖs located in the proto-cosmic space between Hitchcockian suspense (e.g., the chain reaction in The Birds when a man at a service station is knocked over by birds and spills gasoline, which flows across the street to someone lighting a cigarette, who throws his match to the ground, which leads back to the gas station exploding), Marx Brothers comicality, ingenious Rube GoldbergÔÇôness, slapstick, silent films, popular science, and situation comedy, as well as the set-up theatricality, weird pacing, and bizarre poses of porn.

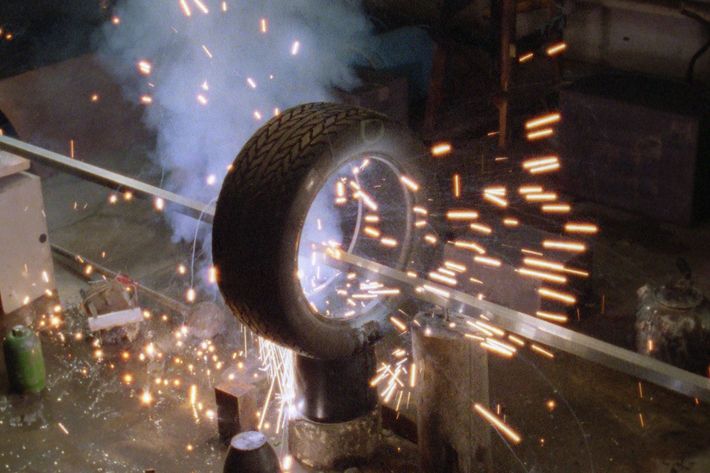

The Way Things Go was shot in what looks like some cold-water Zurich garage. A camera follows apparently without interruption ÔÇö one long Godard Weekend-like shot. In fact, the film took almost a year to produce. The stars of this film are cruddy, 30-gallon black Hefty bags, plastic water bottles, candles, foam, buckets, balloons, fire, and tires toppling over. Behold a ladder or chair tipping over, and maybe bumping a plank or a tabletop, which falls onto tires that roll down and bump into one another until one strikes a match that lights a fuse that makes a rocket-car on a roller skate zoom into some other sequence of absurdity. No part of the film is any more or less important than any other part, and the entropic work as a whole perfectly encapsulates what Robert Smithson said about his own 1970 masterpiece, Spiral Jetty: ÔÇ£A great pleasure arose from seeing all those incoherent structures ÔǪ evidence of a succession of manmade systems mired in abandoned hopes.ÔÇØ The Way Things Go is all about systems forming and breaking down, inertia and structure, perpetual motion, decay, growth, and the Swiss obsession with time. Most of all, itÔÇÖs about how order comes from chaos and chaos from order, and how this harnessed right creates art. ItÔÇÖs an extended rendition of Lynda BenglisÔÇÖs famous 1970s paint spills on the ground, and embodies what Brian Eno meant when he wrote, ÔÇ£Abandon normal instructions; Repetition is a form of change; Emphasize the flaws.ÔÇØ┬áBetter than any other video I can think of, in a very vivid way,┬áThe Way Things Go shows how beauty is that which works,┬áand how, in all its nobility, humility, and believability, beauty produces pleasure and knowledge. Fischli and Weiss have said that by ÔÇ£removing function ÔǪ objects are no longer enslaved by it ÔǪ this opens a space in which to do something else.ÔÇØ The animated undeadness I see makes me believe that objects might possess psychoactive possibilities like mushrooms.

To see how artists get this far out into alchemical space, peruse the early photographs of sausages and salami, called things like Carpet Shop. Or serious-looking, Constructivist-like still lives: cheese graters, wine bottles, silverware, and whatnot in odd arrangements. Soon your eye gleans that the picture is a lie, that what youÔÇÖre seeing is the precarious instant before the arrangement collapses. Fischli and Weiss love deflating highfalutin doctrine. It canÔÇÖt be a coincidence that the doctrine they begin with is the most Swiss one of all: Dada. Elsewhere, thereÔÇÖs a home movie of the artists dressed in rat and panda costumes and walking like Abbot and Costello through Los Angeles, or in the mountains while pontificating on grand philosophies. Dogma fizzles as these modern Flaubert know-it-alls, Bouvard and P├®cuchet, living versions of Tweedledum and Tweedledee, try to order the world around them.

Fischli and Weiss met in the mid-1970s in Zurich, amid the cityÔÇÖs bourgeoning punk-rock scene. Its DIY pieced-togetherness, parody, and being on the edge of chaos connects well to punk. By the end of the 1970s, art had gotten so insular and about itself, and at the same time so pluralistic, that whatever was being made seemed destined only for small audiences of like-minded cognoscenti. Moreover, New York was the epicenter of everything; Europe was wrongly seen as backward by comparison. What were two Swiss misters to do? They began by overturning the authority of authorship itself, preferring instead to embrace the spirit of collaboration and the camaraderie of working together. Plus, two straight men bonding for life keeps their work ticklish. Anyway, itÔÇÖs just this unstable underground mixture that coalesced into their own incredibly influential, wide-ranging, openhearted aesthetic, one that eschews high-minded connoisseurship and heavy doctrine for experience, immediacy, and a fearlessness about asking profound questions in seemingly silly ways, and elevating the seemingly silly to wonderful heights. As Fischli remarked, they want to simultaneously ask, ÔÇ£What is the diameter of the Earth?ÔÇØ and ÔÇ£Why is the earth not a cube?ÔÇØ At the Guggenheim, all this flashes with insight and originality.

At the Guggenheim, you can grasp just how deep this team really is. The epic Suddenly This Overview┬ábegan in 1981, and it consists of over 175 small, unfired clunky clay sculptures. At the time, according to the artists, ÔÇ£working with clay was taboo, regulated to ÔǪ handicraft, domestic creativity.ÔÇØ This is similar to the ways that Kara Walker turned in the 1990s to the outr├® form of cutout paper silhouette. Here are scores of cute, cartoonlike, tabletop-size sculptures. (Think ÔÇ£Far SideÔÇØ comics in clay.) In one work, a couple in bed is titled Mr. and Mrs. Einstein Shortly After the Conception of Their Son, the Genius Albert. A slab with a reptilianlike bump rising out of it is titled The First Fish Decides to Go Ashore. An animal in a mountain pass is titled Fox, Following His Instincts. Suddenly, youÔÇÖre seeing all these moments of wonder, the world unfolding. I see the movement of imaginative magma, all this trancelike magic, wit, fairy illusion, glee, and philosophical substrata. I feel myself crack a smile of reason and delight.

After this mad re-creation of the history of time, and following the choreography of entropy of The Way Things Go, Fischli/Weiss set out on another impossible project, one that took them out of the studio, at last, into the world. Once again, they followed Sol LeWittÔÇÖs credo that ÔÇ£Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically,ÔÇØ or, as John Baldessari put it talking about Chris Burden, ÔÇ£Doing and redoing an absurd idea.ÔÇØ Amen, unorthodox artists. Starting in the late 1980s, they set out to map the planet in images; thousands of simple color pictures of outdoor places, known, unknown, banal, spectacular, monuments, airports, sunsets, palm trees, pyramids, the Taj Mahal, suburban sprawl. About Visible World, they said, ÔÇ£We have a desire to attempt the encyclopedic ÔǪ a longing to grasp the world ÔǪ and at the same time to run it aground.ÔÇØ An eight-hour three-channel silent video consists of all these images slowly blending into one another. In this work, they anticipate our modern, awash-in-images world, foreseeing the titanic shift in the photographic image itself, from carefully composed thing to pictures shot from the hip or pieced together, unconcerned with meticulous formal characteristics, immaterial, existing visually and digitally more than in the material world. I see this mesmerizing work as an animated electronic version of RothkoÔÇÖs bewitching Buddhist TVs. ┬á

Further up the ramp are all the piles of what looks like wood, pedestals, tables, tape, milk cartons, bowls, and paint cans. Basically, it looks like the show is mid-installation. Which is exactly what I thought the afternoon of March 19, 1994, when I walked into the Sonnabend Gallery to see the new Fischli/Weiss show. I looked in, saw all this stuff scattered about, assumed the gallery wasnt done with the show, got huffy, and left. It turns out every object is a perfectly fabricated painted polyurethane replica. Saying they wanted to work as normal as possible  straightforward, they invented normcore. As Fischli put it, people thought there was no show to visit  that the objects belonged to real life, so they werent interested in them. Many refer to Fischli/Weisss art as based in the readymade. The artists protest their art is the complete opposite of the readymade  we have to make them ready! That theyve gone to such lengths to falsify things so worthless and everyday, invested all this labor into making insubstantial and unimportant things as perfectly as they can be made by hand, creates a confusion in the mind, a flooding of information whereby the eye pours over this stuff looking for glitches or mistakes, until the space between the readymade and the deeply made collapses into a beautiful black hole of sculptural meaning. This is where their work really opens a space between found objects, installation, and conceptualism. This cleavage has changed almost all such work that has followed, infusing art with an informal, investigative eccentricity. And for all the irony, wit, humor, and cunning in their art, it all radiates earnestness, sincerity, and a deeply human doggedness and warmth.

And so it goes all the way to the final gallery with The Raft, another trompe lÔÇÖoeil bunch of crates, barrels, chairs, shoes, cooking utensils, a suckling pig, and more, all surrounded by heads of hippopotamuses and alligators. Maybe itÔÇÖs about that age-old question: What would you take to a desert island? Perhaps the answer is in the animals, the way that 90 percent of everything we see is hidden below the surface of perception. Whatever; revel in this show, and know it should always be a Fischli/Weiss moment.┬á

*This article appears in the February 22, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.