Around 8:04 p.m. last night, the lights dimmed at New York’s Beacon Theatre and Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York” played over the PA. I wouldn’t call it the most surprising choice, considering that the audience was there to see Jerry Seinfeld’s second show in a yearlong residency at the storied venue. Then an announcer came on — “Good evening, New York City, and welcome to the 2016 Jerry Seinfeld show” — and I, like everyone else, didn’t even stop the conversation I was having, it was so innocuous. “Please welcome Jerry’s very special guest …” The announcer paused there, and I still didn’t think much of it. It’s probably Tom Papa, I thought, Seinfeld’s regular opener, who is a very fine stand-up but undoubtedly gets called a “very special guest” mostly out of politeness. But the announcer’s pause continued, and I wondered if he might say “Paul Simon,” as there was a guitar mic onstage and I have to assume Seinfeld is friends with Simon, you know, just from being famous guys — hell, Tom Hanks was in the audience. Then he said it: “Mr. Steve Martin.” I lost all of my shit. I screamed a scream I was familiar with, as it’s the sort of scream I’ve heard at comedy shows for years when some celebrity — be it Chris Rock, Dave Chappelle, or Louis C.K. — drops in on a show unannounced; however, this time it was coming from my mouth. This was a very special guest.

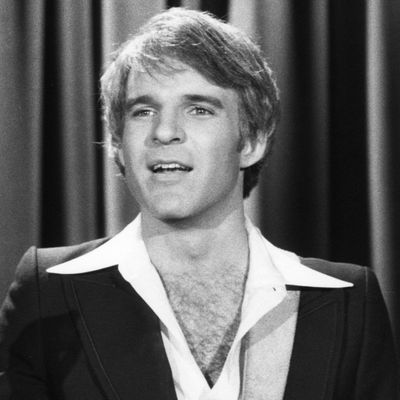

In 1981, Steve Martin was the biggest stand-up in the country. He was arguably the biggest stand-up ever up until that point, regularly selling out amphitheaters when other top names were still playing clubs. And then he just stopped. He played a show and, after the show, decided not to do stand-up anymore. “My act was conceptual. Once the concept was stated, and everybody understood it, it was done,” Martin wrote in his classic 2007 memoir Born Standing Up. “It was about coming to the end of the road. There was no way to live on in that persona. I had to take that fabulous luck of not being remembered as that, exclusively. You know, I didn’t announce that I was stopping. I just stopped.” It would be like if, 25 years from now, you realized that Kevin Hart’s last tour — the one that sold out basketball arenas across the country — was really the last tour. It’s the story of legends, one frequently discussed among comedians. He just stopped.

Until last night. There was a banjo onstage, which I didn’t notice at first, but Martin didn’t walk over to it right away. He walked up to the mic stand and took the mic off. He didn’t put the stand behind him, however, as veteran comics do, to signify, I’m not going anywhere. Martin wanted the crutch; he wanted the out. “Thank you. Jerry couldn’t make it tonight … Have a safe ride home!” which is a solid enough opener, a thing he cares a lot about. “Actually, I’m here tonight because of that old showbiz saying: Never lose a bet to Jerry,” he continued, referring to his episode as a guest on Seinfeld’s web series Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. Though there wasn’t technically a bet made during the episode, rewatching it now, the whole thing feels like Seinfeld making a sales pitch for Martin to try stand-up again. See, not only does Steve Martin not perform stand-up, besides the memoir, Steve Martin doesn’t even talk about stand-up, at least publicly. There was the 2010 92Y debacle, in which he was so intent to only talk about art that a 92Y staff member brought a note to the interview — mid-show — asking for them to “discuss Steve’s career.” I can confirm, from personal experience, that he doesn’t want to be interviewed about it. But Seinfeld is different — he’s also a legend; he’s also a stand-up — and he got Martin to talk about that time at length. In the episode, Martin does seem a bit tense at first — likely because the conversation is being filmed — but slowly he loosens, joking around and even talking about ideas he has for jokes. Based on what Seinfeld said later at the Beacon, it seems like Seinfeld used this as an opportunity to get Martin back.

So, how was he? It’s always hard to tell with celebrity drop-ins, because the audience gives them a pass for the first few minutes, laughing at everything in a way that is more like friends at a dinner party than an audience who paid to be there, and Martin only did a few minutes, but, looking back at the jokes themselves, I’d say he was mostly pretty good, occasionally almost great, and for one moment truly special. “I’ll be honest with you, right off the top, because I’m a little upset with the Beacon Theatre,” one joke began. “I was backstage and I used the restroom. And there was a sign that read, ‘Employees Must Wash hands.’” Pause. “And I could not find [pause] one employee [pause] to wash my hands.” Man, is that a classic Steve Martin joke. Reading it back, it might read overly jokey or cheesy, but that’s the point. Martin in his prime did comedy that made fun of comedy. He told jokes that were unfunny, but he knew they were unfunny, and the audience knew he knew, and that’s what made them funny. The difference is that last night, he didn’t have the same schlock-y, showbiz-caricature persona he made famous in the ‘70s — he didn’t do some dumb dance afterward — but you could still see the intention. And his specific, off-kilter rhythm was there (which is why I transcribed the pauses), where he hides the punch line so the audience isn’t just being told when to laugh, allowing them to surprise themselves with when they laugh. A technique he pushed further with his next joke, the aforementioned special moment.

Here is the joke in full, as I was able to write it down:

By the way, I apologize for the ticket prices. [Pause.] I know it seems expensive, because there is like one guy, two guys, and a couple of mics, but it’s not that way. There are like four sound people, and two lighting people, and [pause] drivers, and wardrobe people, and catering, and someone to walk Jerry’s Fitbit around. [Pause.] A celebrity look-alike, in case Steve doesn’t feel like going on. Steve says hi, by the way.

I’ve seen a lot of live comedy. I’ve seen all the celebrity drop-ins I mentioned above. Hell, I saw Jerry Seinfeld destroy about five minutes later. But this was easily one of the most exhilarating moments I’ve ever had as a comedy audience member. This was the Steve Martin whose albums I’ve listened to my whole life, whose copy of an old set list I bought on eBay and hung on my wall, who shaped modern comedy. The faux-entertainer shtick was clearly articulated, as Martin was using the sort of Hollywood, very fake, apologetic tone. And the use of rhythm was masterful. The joke, which gets lost a bit when typed out, builds by not building. The biggest laugh, arguably, came around the “and” in “and drivers.” It’s so classic Steve Martin, I found it hard to think of an analogue in music. By their nature, musicians play their old songs, which is supposed to remind you exactly of when they were great but doesn’t really. Watching Steve Martin tell that joke was like if, in the middle of a modern-day Bob Dylan set of gurgles and growls, he brought out a time machine, turned the dial to 1965, and had young Bob Dylan come out to sing “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.”

After the show, my friend doubted whether this counted as a return to stand-up. Martin told jokes that he has probably been telling for years in between songs with his bluegrass band. And she was likely right about the jokes — especially considering he performed half the set sitting down with his banjo — but it was not the same thing. Steve Martin hasn’t performed stand-up in roughly 35 years — he hasn’t not been funny; he hasn’t not stood up and told jokes, say, at Saturday Night Live or some awards show — he hasn’t gotten onstage in front of an audience explicitly expecting stand-up and performed stand-up. Sure, you have to imagine any Steve Martin bluegrass audience is expecting jokes, but they also are mostly anticipating bluegrass. Last night, there were no expectations once he grabbed the microphone, and in that way, he was just like every other stand-up comedian performing in the city at the same time. The difference is maybe imperceptible to us, but it definitely wasn’t to Steve Martin.

Midway through Martin’s little banjo medley, Seinfeld came onstage with a banjo case and jokingly made a face that said, “Okay, wrap it up.” So he did. And Martin got up from his stool, walked over to Seinfeld, shook his hand in the perfunctory way comedians shake the hand of the comedian who’s up next at the mic, and said, “Thank you.” Later in the show, before going into a question-and-answer encore, Seinfeld asked the audience to give one more hand to Steve Martin. “That is really the thrill of my career,” Seinfeld added. Same.