Call it the MetNey. The Metropolitan MuseumÔÇÖs huge new eight-year annexing of the Whitney MuseumÔÇÖs former Madison Avenue location is potentially landscape-changing, creating a new place where modern and contemporary art can be seen alongside 50 centuries of art from every culture. If the Met gets this right ÔÇö and doesnÔÇÖt just tout big names and trophy art, make tepid exhibitions, become institutionally uncollegial by taking traveling exhibitions and artists from other local museums, or mount ┬ápandering shows that place generic and politically correct aesthetics over good art ÔÇö New York is about to get one tremendous museum better. That hasnÔÇÖt happened since the scene-altering founding of the New Museum in 1977. And thereÔÇÖs enormous goodwill and crossed fingers about the MetÔÇÖs endeavor, in part because there is something deeply unsettled, and unsettling, about the project. All know that ahead lies a treacherous balancing act ÔÇö creative thinking, self-examination, scholarship, good staff decisions, and sterling curatorship are all critical for the success of the Met Breuer. The balancing act is treacherous among other reasons because the new enterprise has actually been rushed of late and is actually out of character for the museum, a sign that the Met is trying to reinvent itself, at least somewhat, away from its mission as a storehouse of the canon and toward a new one that looks backward and forward at once, while wielding the equivalent of the museological nuclear codes and muscle able to pull in loans and collections that no other American museum could conceive of. For the Met Breuer to misfire or simply fizzle would betray the credibility built on the backs of artists over the last 100 years. That would be tragic. Especially for people like me who pledge allegiance to the Met.

ThatÔÇÖs why it makes me heartsick to say that while the MetÔÇÖs big initial two-floor blockbuster of ÔÇ£unfinishedÔÇØ masterpieces drawn from 500 years of Western art will entice audiences, promising a look under the skirt of art to see the secrets of artistic process, the overall exhibition, ÔÇ£Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible,ÔÇØ is half-baked. Worse, when this show gets to art after 1965 ÔÇö the work one imagines would be the center of the inaugural show at this new contemporary wing ÔÇö it veers into such unoriginal thinking that one almost winces. Why? Starting in the 19th century almost the entire thrust of art history has been about disrupting finished integrated surfaces and other levels of optical integrity, and since the 1950s itÔÇÖs fair to say that most artists have experimented with degrees of deskilling, unfinishedness, and accident: Think of Sol LeWittÔÇÖs written instructions to other people to make his drawings; PollockÔÇÖs drips; PicassoÔÇÖs fragged ice-field-like compositions; MatisseÔÇÖs vast patches of canvas only lightly or altogether uncovered; de KooningÔÇÖs wild-style brushwork; all of Basquiat; or Lynda Benglis pouring paint on gallery floors. Indeed, the entire blight of recent Zombie Formalism derives entirely from this old stylistic doctrine. Easy fun notwithstanding, this is simply not a fresh or invigorating perspective on postwar art. Process art and the conscious redefinition of finish is the lingua franca of art after 1945, which means IÔÇÖve probably seen more than 100 shows dealing with subjects similar to this one, many of them more inspired in their presentation of contemporary work.

But what makes this one different ÔÇö what makes the MetÔÇÖs whole project so exciting, and what saves this show in particular from itself ÔÇö is that IÔÇÖve never seen a show like this one with anything like this abundance, or quality, of earlier material. The showÔÇÖs very first painting, TitianÔÇÖs 1570s The Flaying of Marsyas, for instance, is an otherworldly epic of condensed density and erotic articulation of form and suffering, in ravishing russet colors, that made me stop in front of it for more than a half-hour trying to unpack the different psychologies in play. Nearby is an inventor of the Northern Renaissance and the person who brings the Italian Renaissance over the Alps, Albrecht D├╝rerÔÇÖs portrait Salvator Mundi, left unfinished in 1505 perhaps because the artist fled plague-ridden Nuremberg for Venice; the work was later restored in woeful ways, then re-restored back, and now lets us revel in soft underdrawing, giving us this tremulous Savior of the World, equal parts flesh, spirit, sadness, dignity, suffering, and reassurance. We turn molten with emotion. Or the sight of Jan van EyckÔÇÖs barely painted Saint Barbara, from 1437, that makes you know that not only was this first user of oil paint among the best who ever lived, but that the drawing below his surfaces may be the finest heights this medium ever reached as well.

This redoubles when we look back one gallery and right next to that first Titian is another, The Agony in the Garden (1558ÔÇô1562), that reminds us of AudenÔÇÖs great line ÔÇ£About suffering they were never wrong, / The Old Masters.ÔÇØ A glowing Christ begs God to change his destiny as the entire lower portion of the painting fills with the elephantine figure coming to arrest Jesus and begin the process of subjecting him to an excruciating death. The unfinishedness of the surface is a metaphor for the tearing apart of ChristÔÇÖs body, and we can see how the artist plotted an upper and lower stage for the picture, how he lays in grayish grounds and tonal washes set against highlighted explosions of fast-applied paint. In these parts of the show the metaphors of unfinishedness resound.

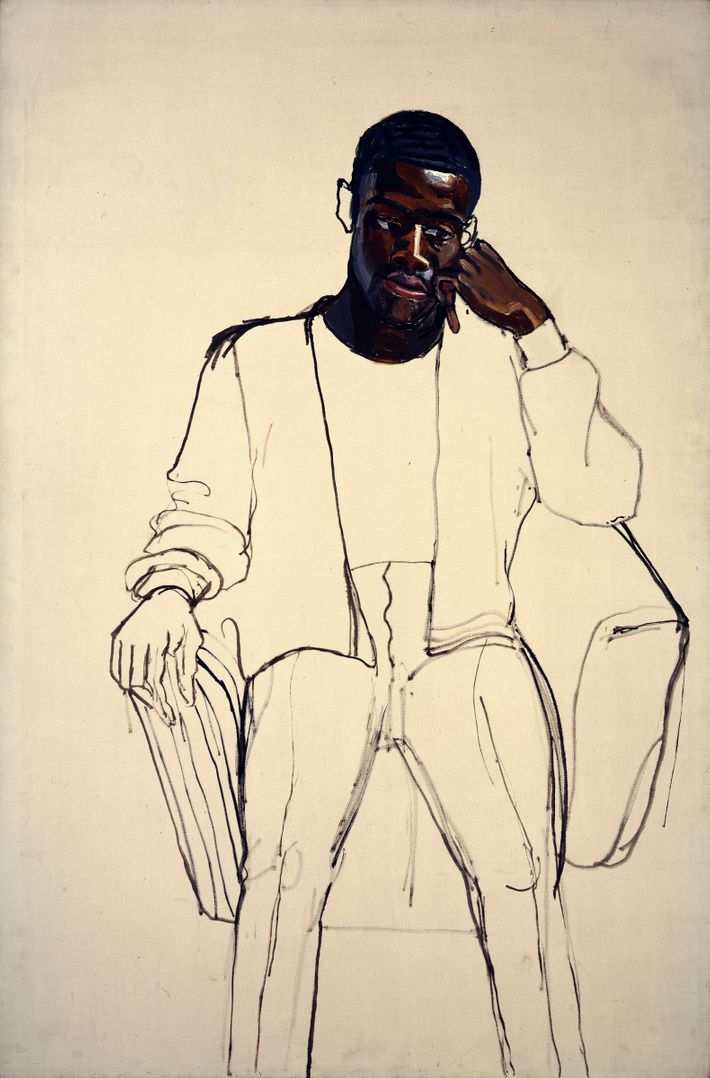

Closer to the present is a heartbreaking unfinished late van Gogh that made me rage at the artist for killing himself when he was finally integrating drawing, paint strokes, and picture. At one point of ÔÇ£UnfinishedÔÇØ I thought, Maybe everything comes back to Titian, as I looked at Alice NeelÔÇÖs 1965 portrait of a black draftee who sat for the artist once, promising to return, but never did. His stripped skin and fragmented figure let an old truth about who fights our wars crash back into our consciousness and reconnects to TitianÔÇÖs picture of a forsaken satyr being skinned alive by the powers of Apollo.

But mostly viewers will go from work to work in a Wheres Waldo? kind of way, looking for the unfinished bit without the show ever presenting the incredible existential implications, vertigo, tragedies, losses of faith, failures of fortune, historical and societal problems that finishing or not finishing a work of art means. Thats because while the unfinished conceit is fun, its also really limiting, because anything unfinished automatically looks a little modern, as unfinishedness is our aesthetic: About the Mets venture I thought of D.H. Lawrence writing, The world fears a new experience more than it fears anything  it hurts horribly.

In fact thereÔÇÖs so much about ÔÇ£UnfinishedÔÇØ that represents the MetÔÇÖs mixed history with the art of its own time that it could be a case study. For more than 100 years the Met has excelled at presenting the art of the last 50 centuries. That is, except one. The Met has been iffy to clueless around postwar modernism and contemporary art. For a while it shunned new art altogether, then had a love affair with British painters like Francis Bacon, Howard Hodgkin, and Lucian Freud, who all somehow represented an Anglophile safe haven away from the explosion of painting taking place around the globe starting in the 1980s. (That old chauvinism rises here in there being three Freuds, where one would have done it.) In 2000, dapper former director Philippe de Montebello groused that a work of Kiki SmithÔÇÖs was ÔÇ£disgusting and devoid of any craft or aesthetic merit.ÔÇØ Following that bad catechism, he ordered ÔÇ£Not on my watchÔÇØ to a request to display Damien HirstÔÇÖs most famous sculpture, a shark suspended in formaldehyde. Unfortunately for them, this turn away from contemporary happened as the art world as a whole began moving away from Old Masters and even prewar masterpieces toward a sort of cult of the new and the now. The MetÔÇÖs response, which came in 2012, was one of the most feckless exhibitions in recent memory, ÔÇ£Regarding Warhol,ÔÇØ┬áa mishmash of big-name artists who all supposedly represented what the museum called ÔÇ£the Warhol phenomenonÔÇØ (a show of market-approved artists whose inclusions reduced everything to celebrity, flash, or fun, and completely defanged all the radical ways of making art that Pop represents).┬áIt didnÔÇÖt help that of the showÔÇÖs 60 artists eight of them happened to show with Larry Gagosian.

The Met Breuer is current director Thomas Campbells all-out attempt at course correction. Of contemporary art he has said that theres a sort of neo-Renaissance that the Met should be part of, adding the Met is not  going to cut itself off from the supporters of the future. For better or worse, hes right about this museum not sitting out the present and recent past while the vast majority of todays collectors are involved in modern and contemporary art. And how could they sit it out? Its estimated that almost half of the Mets 38 trustees participate in this sector of the art world. Traditionalists are in a huff that Campbell has gone to art fairs, biennials, and galleries, and has even attempted to pay attention to the market. About that, they should relax  or, as artist and critic Walter Robinson recently wrote, strive to overcome their revulsion for the market, if only because booming art sales are singularly responsible for todays supersized art world. I cant think of any major museum director who doesnt occasionally show up at these places.

Nevertheless, thereÔÇÖs no denying that the Met getting involved with contemporary and modern art is a shot over every museum bow. What is perhaps the worldÔÇÖs most powerful museum is now making an even bigger claim for itself ÔÇö and one that is undeniably exciting. Imagine collectors seeing their Marlene Dumas, Brice Marden, Luc Tuymans, Urs Fischer, or Jean-Michel Basquiat (all included in ÔÇ£UnfinishedÔÇØ) installed alongside Vel├ízquez, Leonardo, Goya, Manet, Mondrian, or van Gogh. Further up the food chain, less than two years ago Leonard A. Lauder gave more than 80 A-list Cubist works to the Met. Adding to that, the Met has the clout to pull in almost any loan it asks for, making it more formidable still, and that much more a draw on the pool of possible trustees, donors, collectors, and other contributors. This doesnÔÇÖt mean that the Met is going to put everyone else out of business. The Modern, even with all its intractable space problems, has and will always have the greatest collection of modernism on earth. The Whitney, meanwhile, is devoted to the art of North America and with its debut exhibition last summer, ÔÇ£America Is Hard to See,ÔÇØ┬ájust established that this art alone can make the museum great for decades to come. The Brooklyn Museum may be being reborn under new director Anne Pasternak. The MetÔÇÖs great difference is its encyclopedic scope and collection. Not only does it have more space, money, and art than any New York museum, it can do something no other American museum can do to this degree and in such depth. It can shatter the canon of modern and contemporary art, placing it in context not only with much older art but with art and ethnographic objects from all over the world. If this is done right it can alter the way the world looks at art and the way that art looks to the world. If the Met has guts and vision it can be a giant step in the realization of every kind of multiculturalism, finally opening things up.

But if the mission is to incorporate new masterpieces into the old collection, why bifurcate the museum into two buildings? Why not just do this in the MetÔÇÖs beautiful accommodating Beaux-Arts building? It canÔÇÖt be the relatively puny, roughly 25,000 square feet of added exhibition space. The Met has more square footage than any museum in Manhattan ÔÇö something like 2 million square feet. It owns more than a million objects. It has the economic, social, and political clout to get the city to agree to almost anything it wants around building, remodeling, and additions. Inside the old museum right now there are many tens of thousands of misused square feet ripe for readaptation. Or razing and redoing altogether ÔÇö such as the useless-for-art,┬áminimum-security-prison-like Lehman Wing.

Maybe the Met is looking to the poster child for a major museum splitting in two. In 2000, Tate Gallery divided into Tate Britain and Tate Modern. NothingÔÇÖs been the same since. In good ways and bad, sometimes very bad ÔÇö as with sideshow spectacles of people walking through fake rain or pop stars in arrant atriums. Nevertheless, Tate Modern was a game-changer in terms of making art super-populist and making easy-thematic exhibitions and displaying gigantic works of contemporary art in the museumÔÇÖs five-story, 36,000-square-foot Turbine Hall. (I wish our confined island-home had that kind of raw building stock available for reuse for modern and contemporary art.) Whatever you make of Tate, it was never about integrating 5,000 years of world art. The Breuer is beautifully Brutalist but itÔÇÖs no Turbine Hall or Tate in any way. Thank God!

Which brings us to the person Campbell charged with overseeing the MetÔÇÖs new adventure: Sheena Wagstaff is the chairperson of the museumÔÇÖs new Department of Modern and Contemporary Art. She is a former chief curator at Tate Modern. Among her initial hires was her former Tate Modern colleague, curator of international modern art Nicholas Cullinan. In the catalogue, Campbell says that Cullinan┬áÔÇö later with co-curator Andrea Bayer ÔÇö ÔÇ£initiatedÔÇØ the ÔÇ£UnfinishedÔÇØ exhibition. When I read who cooked up the idea I thought,┬áTwo former Tate curators! ThatÔÇÖs why the way this show has been done seems fishy and a tad Tate-ish.┬áBefore I explain why┬áÔÇö Cullinan then left ÔÇ£UnfinishedÔÇØ unfinished to become director of the National Portrait Gallery in London. Meanwhile Wagstaff hired another former curator at Tate Modern, Iria Candela, and also established Met Breuer departments for North African, Middle Eastern, Turkish, South Asian, and Latin American art, among others. I love that the Met is spreading out around modern and contemporary art. Yet this list of countries echoes something like a modern Raj ÔÇö one that might find department heads traveling the world to many of the very former colonies of the British Empire, bringing back objects and artists. Cynicism aside, the Met is essentially saying that it is not going to be all about white-male and first-world artists. Amen. Indeed, even at worst thereÔÇÖs a real benefit: Just as mediocre white male artists have been allowed latitude, so soon will women and artists from around the world; that way weÔÇÖd at least have a more accurate idea of mediocre art. Can I get another amen?

This is precisely where ÔÇ£UnfinishedÔÇØ┬áfails catastrophically ÔÇö even more catastrophically than in its approach to the contemporary ÔÇ£unfinished.ÔÇØ Every message sent by the Met Breuer before now has been about opening up the canon, reorienting the Met away from Eurocentric thinking, breaking down art-historical barriers and exploring the geographic immensity of art! ÔÇ£UnfinishedÔÇØ┬álimits itself to 500 years. Fine. Much more would become overwhelming. But the showÔÇÖs geography is the exact same terrain that exhibitions like this always are: Western art! The whole raison dÔÇÖ├¬tre of the Met Breuer was to integrate international art across the ages. Just this week co-curator Kelly Baum told Artsy that not contextualizing art of different times and places ÔÇ£presents a distorted viewÔÇØ of art. Wagstaff underscores this, saying that the museumÔÇÖs ÔÇ£idea of history is an aggregate of simultaneous narratives whose significance morphs.ÔÇØ ┬á

That pain reverberates when we think of the revelations that might have been had! The deepenings. IÔÇÖm not talking about typical primitivist comparisons between Cubism and African sculpture. (As it is there are moments of such curatorial obviousness ÔÇö placing things that look vaguely alike next to one another ÔÇö that it conjures groupings IÔÇÖve seen in Curatorial Study shows.) But think if the Met had the nerve, courage, and conviction of its mandate. Rather than just comparing, say, a Jacques-Louis David portrait from around the French Revolution and Benjamin WestÔÇÖs unfinished portrait of the American Founding Fathers with a picture of Napoleon by Elizabeth Peyton, fathom seeing ÔÇö from around the same time ÔÇö a wooden statue from modern Zaire of a contemporary king, a commemorative terracotta portrait from Ghana, an Indonesian ship cloth showing local armies, a feather god by an anonymous Polynesian artist, an erotic Japanese Shunga woodblock of kings and queens doing unspeakable fabulous things with one another. Or an illumination from India of those emperors, not just FranceÔÇÖs! Korea, Japan, and China raised the idea of unfinishedness to such sublime heights that the aesthetic even has a name: wabi-sabi,┬áthe acceptance of transience and imperfection. No wabi-sabi here, though. If the show is about Western unfinishedness then whereÔÇÖs WhistlerÔÇÖs Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, among the works that triggered one of the most notorious lawsuits in all of art when the artist was sued by the most powerful critic of the time, John Ruskin, as ÔÇ£flinging a pot of paint in the publicÔÇÖs faceÔÇØ? IÔÇÖm sure the Detroit Institute of Arts would have been more than happy to accommodate.

Oversight and slights like this cascade and metastasize. One of the great experimenters of early-19th century process, John Constable, isnÔÇÖt on hand. Or the early-20th-century batshit Australian, Sidney Nolan, who painted smooshy images of an outlaw riding around the outback with a steel bucket on his head! Closer to the present, rather than pairing Rodin with yet another Bruce Nauman, Robert Smithson, and some silly new Urs Fischer (that is just kitsch), what would have happened if we saw a tide map made of sticks from the South Pacific, an unfinished Benin bronze from Nigeria, a partly destroyed Tibetan mandala sand painting, a carved Quila wood figure from Papua New Guinea! These are all masterpieces and all ask questions about ideas of incompleteness. Should I even mention all the unfinished-looking works by North American so-called outsider artists Mart├¡n Ram├¡rez, Henry Darger, and Bill Traylor? This last was even given a stamp last year by the U.S. Postal Service!┬á

In a debut show in a new building of an institution putting everything on the line in part to integrate international art, this kind of insular blinkering isnÔÇÖt just mind-boggling and infuriating, it borders on the criminal. In fairness, there is a wondrous second-floor show of Indian Minimalist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937ÔÇô1990) that does find the Met looking beyond its own belly button.

With all of this in mind, a mysterious gift is being bestowed in this new building; one that, despite all, will be my temporary guide in my high hopes for this venture. Last summer the Whitney so successfully established a new identity in its downtown Renzo Piano building that when we walk through the Met Breuer there are no ghosts haunting or hexing the place. No MetNey. To its tremendous credit the redo of the Breuer is perfect! All the Met essentially did was clean the place up, change the lightbulbs, and get rid of a little of the dinginess. (I even like the new logo, which is just fine.)

As a result something wonderful can happen here. About 40 percent of the show comes from the MetÔÇÖs collection, yet seeing these familiar pieces in this new building made me use internal muscles I hadnÔÇÖt used on these works before, mapping new psychic geographies, hearing new secrets. Proust was right that when we disrupt habit it allows us to break memory, transcend the past, create new cradles of thought, and make us sense other essences┬áÔÇö rebaptizing us, re-sanctifying dreams weÔÇÖve always had but that now seem new again.

ThatÔÇÖs when I also saw the dreams that all this may point to. I surmise that the Met Breuer will be here these eight years and another similar lease period. Meanwhile, the museum will finally go ahead with its many building and rebuilding projects, redoing bad spaces, altering galleries, razing others. At the same time, letÔÇÖs pray that the Met will finally be able to break the horrible legal stranglehold of the many collector stipulations placed on the museum that forbid works of art from being exhibited outside their named wing. Then the Met could shatter antiquated agreements that hold art hostage, agreements enforcing that works by Vuillard, Matisse, Picasso, van Gogh, C├®zanne, and others canÔÇÖt be seen together (and in fact are often required to be in two or three different locations within the Lehman, Annenberg, Smart, and other collections).┬áThen the Met, having hopefully established itself in the Breuer as a museum of modern and even contemporary art and made it inclusive, could vacate the space and consolidate all of its art into one grand integrated building, under one roof, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all art.