Better Call Saul co-creators Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould credit the AMC series’ composer, Dave Porter, and music supervisor Thomas Golubic for bringing in a broad range of musical influences that nail who Saul Goodman is. They compiled an eclectic soundtrack that includes classic Dave Brubeck jazz, down-home country singer Bobby Bare, a Vivaldi concerto, classic rock, and modern blues. “You get a glimpse into Jimmy’s head. He zigs and zags in very unpredictable ways,” says Gilligan (who, alongside Gould, also co-wrote a Spanish-language song, “Yo Soy Saul,” with L.A. band Mariachi Bandido, to approximate the spirit of the titular lawyer, a.k.a. Jimmy McGill). For their part, Gilligan and Gould have a specific set of cinematic, artistic, and geographical influences they used to flesh out the worlds of both of their AMC shows. Vulture spoke to the showrunners about how cowboys, Coppola, a classic painting, and more influenced Better Call Saul and its predecessor, Breaking Bad.

New Mexico

Vince Gilligan: New Mexico is a found inspiration. When I first wrote Breaking Bad, I intended to set it in Riverside, California. That’s where I wanted to shoot, because I like the idea of sleeping in my own bed every night and being able to visit the set. Early on, financial realities hit hard and it was made aware to me that if we shot in a state that could give us a little bit of a rebate, give us a little financial understanding, our dollar would go farther. We wound up going to New Mexico and it was the luckiest thing that ever happened to the show. Now I have a home in New Mexico. It became something of a central character in Breaking Bad. I don’t think the idea of portraying Breaking Bad as a modern-day Western would have occurred to me if we were shooting in Southern California. New Mexico inspires the wide-angle shots we use on both television series. Very often there are beautiful, puffy, ice-creamy cumulus clouds that stand out very vividly on the dark-blue skies. Any time we can show a wide shot of the New Mexico landscape and do our best to make it seem like an Ernst Haas photo, I’m as happy as a clam.

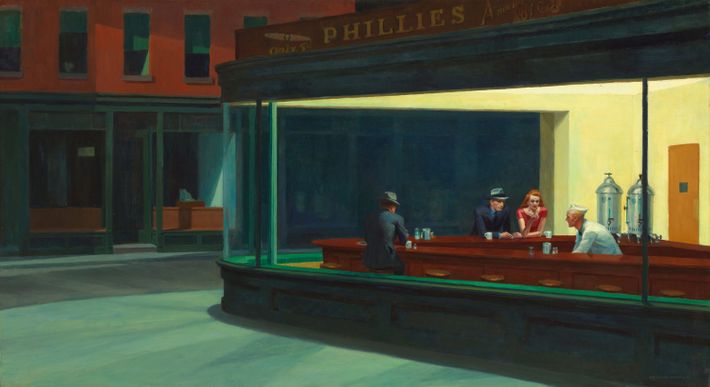

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks

VG: We’ve been ripping off Edward Hopper shamelessly over the last two years, at least. We love that image of an island of light surrounded by an ocean of darkness, two lonely people sitting at a counter drinking coffee at an all-night diner surrounded by loneliness and gloom. We’ve emulated that shot a great many times. You will definitely see some overt visual references to it in the last couple of episodes of season two coming up. We go for that every chance we get. Sometimes you get an image in your head and it’s hard to shake, sort of like Richard Dreyfuss’s character in Close Encounters — that image of that devil’s tower he had to make out of mashed potatoes. We have to put this in our show as many times as possible.

Peter Gould: I have a personal connection to Hopper and that school of painting. My parents were both painters and they studied with a contemporary of Hopper’s, Reginald Marsh. One of my father’s paintings is my logo at the end of each episode. Most of my father’s paintings are all in that vein, where there’s a sense of urban loneliness, and there are a lot of paintings he did of old men eating in diners by themselves. Sometimes I think about that when we have a scene with Mike Ehrmantraut.

The Westerns of Sergio Leone and John Ford

PG: One of the things we both love about those movies is the characters have such recognizable silhouettes. They are immediately distinguishable from each other and maybe even sometimes a little bigger than life. We reference the iconic cowboy quite a bit, but then there’s this other kind of character you see in Westerns which is the tenderfoot from the East, the flimflam man or the snake-oil salesman. Jimmy McGill comes out to the West very much in the tradition of the guys with a covered wagon and a patent medicine show and the fast talker. He is the city slicker in this landscape full of cowboys.

VG: There’s the sense of a man or a woman being in the right place for them. There’s a sense of something that’s ephemeral, that’s not going to last, and certainly that was, as you can imagine, a strong inspiration on Breaking Bad, because the very premise from the beginning was that this character’s not going to last. He’s given a death sentence in the very first episode, so that vanishing West, that feeling of “I better enjoy this while it lasts because it’s not going to last long,” that in-built bittersweetness, that nostalgia I feel from the best Westerns makes them an inspiration.

The Godfather

VG: I don’t know where to begin with The Godfather except to say that’s a movie I could watch pretty much every night for the rest of my life. Every time it’s on AMC, I tune in, which is crazy because I have all the Blu-rays. When I say The Godfather, I’m talking about one and two. No offense to the third one, but I’m pretending it never happened. One and two, it’s a crash course in storytelling. There’s so much to be learned. It teaches you confidence in stillness and quietude. The cutting pattern and the composition of The Godfather is so different than what typically is in vogue nowadays, where there’s hypercaffeinated cutting that doesn’t necessarily accomplish everything in story tones. Coppola had the confidence to hang back wide and not cut until it was damn well time to cut. The Godfather teaches you restraint. We try to emulate that on Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. We like to stay wide and keep the cutting patterns slow.

PG: One thing we take from The Godfather is the freedom to move about in time, especially Godfather II. It’s one of the most innovative uses of cross-cutting between decades and characters, but it all adds up to one story. Sometimes you see the effect first and then the cause, and there’s something fascinating about that. Talking about Westerns, there’s also a nostalgia to it, but then there’s also the feeling of starting new, which is one thing in common between the Western and The Godfather. You’re seeing people who are creating their own worlds in a new world, America. The question is, “How is it going to be here?”

The French Connection

VG: I don’t know if The French Connection completely qualifies for Better Call Saul, but it was definitely an influence for me on the pilot of Breaking Bad. It’s another movie I could watch once a week for the rest of my life. It came out in 1971 but still, to my eyes, looks as fresh and original as anything being currently made. It does not ever feel dated, and I can’t even figure out why that is, because it’s very much a very specific time and place. What I took from it on Breaking Bad in the pilot was the stable handheld look, which we have now moved away from on Better Call Saul just to differentiate. But there’s a newsreel-type feel to the photography. They shot it holding the cameras as steadily as they humanly could. There’s always a bit of breathing, there’s always a bit of life to these shots, not this kind of “let’s whip the camera around like we’re having a seizure” shit. There’s restraint.

Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist

PG: We are stuck in the ‘70s, aren’t we? When we started Better Call Saul, we started looking at different movies and art to try to figure out what this new show was going to look like, and we kept coming back to imagery from The Conformist. Bertolucci directed it, but it was Vittorio Storaro who was the DP and Ferdinando Scarfiotti was the production designer. [It] uses color in such interesting ways. It goes through a man’s life and his memories, and the color is different in different eras, but there are some very unusual, striking compositions where characters will be not framed the way one would expect. It’s not classical good composition, but the compositions all had good meaning.

VG: There’s a great shot in the final episode of season one of Better Call Saul. Peter directed it and it’s toward of the end of the episode when Jimmy is in the parking lot of the courthouse and he’s debating going into the courthouse and taking this job that he’s been offered at this big law firm, Davis and Main. Peter put Jimmy low and to the far right of the frame so you’ve got this wide frame of the big building in the background. Jimmy is a small figure, just head and shoulders down in the lower extreme right of the frame.

That shot to me is particularly striking — a little of that stuff goes a long way. It fits the character’s mood and inner turmoil in that moment, so story-wise it works like gangbusters. It’s the kind of thing, like, it’s too much salt on your French fries. Just the right amount of seasoning makes for the best stew, so to speak.

This interview has been edited and condensed.