Attending high school in Atlanta at any point between 2000 and 2006 was truly a charmed, near-delusional experience. It must have been like being from a city that has won multiple championships in the same year, like Boston when the Red Sox, Patriots, and Celtics were all annoyingly good at the same time. In Atlanta during this moment, it was not sports ÔÇö it was music, an unprecedented boom of which gave even the average Atlantan the confidence to feel as if they, too, were a star. And it wasnÔÇÖt just the high volume of music coming from Atlanta ÔÇö so much of it was about Atlanta, further turning a 15-year-old with only a Visa Buxx card and a learnerÔÇÖs permit into a boy who honestly felt as if his birthright was holy. In no way was this the golden age of Atlanta rap ÔÇö the Organized Noize era ÔÇö this was the product of that era. We were the kids who grew up on Organized, not with;┬áAquemini and certainly Stankonia were ours in real time, but we were a little too young to remember the release day of the LaFace Christmas album.

In Atlanta, in the first half of the first decade of the new millennium, your life revolved around trying to out-Atlanta the next person who also lived in Atlanta. If you had a home basketball game, your layup line mix had to be more ATL than any other schoolÔÇÖs. If you were controlling the music at a house party, the music on your click-wheel iPod had to be more ATL than the previous makeshift DJÔÇÖs. And if someone got in your car, that burned CD better not have had a track by an artist who wasnÔÇÖt from the 404 or 770.

It was all about how you showed your pride, outwardly ÔÇö in your words, where you spent your time, how you dressed. That was, until you left home. Because thatÔÇÖs when the pride changes. You were no longer proving yourself among fellow patriots ÔÇö you were defending your homeland in foreign territory. Suddenly, itÔÇÖs 2005, and youÔÇÖve decided to do the reverse hajj, from Mecca to New Hampshire.

I showed up at college with the equivalent of a scarlet letter and a grenade launcher: a white Falcons No. 7 Michael Vick jersey. It was simultaneously distancing and intriguing ÔÇö but mostly the latter due to the fact that, more than any other moment in history, Atlanta was never cooler to the rest of the country (yes, including the Olympics). All of the stereotypes worked in your favor. People assumed you lived next to Ludacris, hung out at the clubs you were still years away from getting into, everything. And, again, it was all because of the music. Rap music had let the rest of the world in on the Atlanta streets, venues, malls, slang, parks, and local legends that you once only knew if you were from the city. So when I stepped out during the peak, there was fear but also a power that IÔÇÖd never felt at home.

That power only became greater in the spring of 2006. When I returned to college in January after a winter holiday break in Atlanta, I was armed with a battle cry: ÔÇ£Kryptonite (IÔÇÖm on It).ÔÇØ I felt unstoppable. ÔÇ£I be, on that, all night man, I be on it all day (day) straight up, pimp, if you want me you can find me in the A.ÔÇØ When it came on, the three or four Atlanta kids at the party suddenly became Voltron, with everyone just watching our powers combine. Everyone knew and loved the song, but those of us from the city felt like we were extensions of every rapper, every lyric, every note.

After about a month of that, there was ÔÇ£What You KnowÔÇØ by T.I.

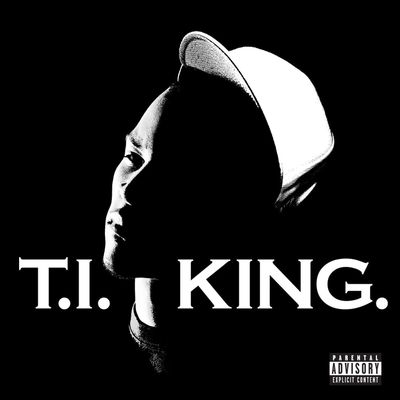

The track was officially released as the first single from King. But it wasnÔÇÖt the first song we knew that might be on the highly awaited fourth album by T.I. Leaks were rampant at this time, with versions of many songs that eventually made it on the album very much out, so much so that T.I. and DJ Drama released a mixtape titled, appropriately, The Leak. ÔÇ£Ride Wit MeÔÇØ was one of the album tracks on the mixtape, as well as a Pimp CÔÇôless ÔÇ£Front BackÔÇØ and a Jamie FoxxÔÇôless ÔÇ£Live in the Sky.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£What You Know,ÔÇØ however, changed everything. T.I. had hits, true bangers, and even a few tracks that you knew would hold up for a long time. But nothing like ÔÇ£What You Know.ÔÇØ This was an anthem. A song that, from that first iconic second, you knew was a beast of a different kind.

That was late January. And then in mid-February, things got even wilder, as the video came out, premiering on BETÔÇÖs Access Granted. ItÔÇÖs a great video, mainly because any visuals surrounding that song would look good, but the final third is what further made this a near-paralyzingly exciting moment to be from Atlanta. In the video, you see a marquee that says ÔÇ£ATL Movie PremiereÔÇØ and then the movie poster for ATL and then T.I. and actress Lauren London step out of a Cadillac Escalade, and then you see what is the rest of the cast of the film.

At that moment, it hit you. Holy shit. Clifford was about to drop King and ATL at the same damn time. And not just for us ÔÇö for everyone.

A month later ÔÇö mid-March ÔÇö I was headed home for spring break, my first of college. IÔÇÖd somehow made it through two-thirds of freshman year and needed that home recharge so I could make it through one final quarter. The first two things IÔÇÖd acquired after getting my momÔÇÖs car and driving around town were a white Braves hat from Lenox Mall and a poster that IÔÇÖd snatched off a wooden telephone pole. One side of the poster was black and the other silver, with T.I.ÔÇÖs face, the familiar cocked, fitted cap atop his head, the album title King, and the released date of March 28. I knew King was coming in a week or so, but didnÔÇÖt realize it was March 28 ÔÇö my birthday. Turning 19 was going to be the best birthday ever.

The energy in the city that week leading up to King/ATL/T.I. week was unreal. Clifford Harris was everywhere ÔÇö billboards, radio, television, anything that could further let you know that T.I. was about to put the city on his back. It was exciting, because rappers didnÔÇÖt have moments like this. Hell, Atlanta didnÔÇÖt have moments like this. Jennifer Lopez had a week like this with J.Lo and The Wedding Planner. But that was Jennifer Lopez. And this was T.I., dropping a film on Friday and an album the previous Tuesday that would also double as the unofficial soundtrack for his Friday film. It truly was the moment everything seemed to come together, not just for T.I. but also for Atlanta. The entire history of hip-hop culture in Atlanta had been building to this moment of synergistic mayhem. Somehow both the music industry and Hollywood had gotten behind a kid from the Bowen Homes projects. In March of 2006, T.I. was winning, but it felt like we all were. The whole world was looking at us. And in true Atlanta fashion, the end result was of secondary importance. We just loved it because everyone was finally watching.

It seemed like the moment things would peak for T.I., but that actually wasnÔÇÖt true. His 2008 album, Paper Trail, was his big pop record (even with some of his goonier hits like ÔÇ£WhatÔÇÖs Up, WhatÔÇÖs HaapninÔÇÖÔÇØ), but King was the peak of T.I. and Atlanta operating as a unit. ItÔÇÖs oddly appropriate that the final track of King┬áis a song called ÔÇ£Bankhead,ÔÇØ named after one of the cityÔÇÖs great neighborhoods, a song that begins like a turn-up funeral procession, but also feels like that moment at the funeral when someone reminds the room that this is actually a celebration of life. If weÔÇÖre talking about an artistÔÇÖs ÔÇ£classic period,ÔÇØ T.I. certainly had one, and King┬áis the end. Between 2003 and 2006, T.I. released three classic albums. Trap Muzik helped introduce a sound, a slang, a style; Urban Legend perfected it; King┬átook it to the masses.

Unfortunately, the day before King┬ácame out, I had to leave Atlanta to go back to school. Classes began on March 28. The night before, however, I reached in my duffel bag and pulled out that King┬áposter, along with an ATL┬ámovie┬áposter IÔÇÖd also purchased, and put them on my dorm-room wall. In that one week, T.I. armed me with enough Atlanta ammunition to last me the rest of freshman year. You already feel invincible when you turn 19. But throw in a film about your city, named after your city, released 72 hours after an album from the same local legend, released on your birthday ÔÇö you couldnÔÇÖt tell me nothing in the spring of 2006.