ÔÇ£Every single one of the works here has a story attached to it,ÔÇØ says Sheena Wagstaff, the British curator hired away from the Tate Modern to direct the MetÔÇÖs dramatic expansion into contemporary art (and into the old Whitney building on Madison Avenue, which itÔÇÖs renting from the Whitney for that purpose). The drawbridge reopens March 18 on the reflagged Brutalist redoubt, and the Met hasnÔÇÖt done much to the building itself ÔÇö the same philanthropistsÔÇÖ names remain inscribed on the galleries ÔÇö but the bluestone floors are polished; thereÔÇÖs a zippy new video-display wall when you first walk in and a new reception desk; the lightbulbs in the lobbyÔÇÖs famous grid of ceiling lamps are now LED; and by this summer there will be a new restaurant. The Whitney had moved its offices out of the fifth floor to make room for more gallery space, but now there are offices there again (Wagstaff remembers that, when she was at the Whitney Independent Study Program in 1982, then-director Tom Armstrong had a little balcony with tomato plants up there). She gave me a walk-through of the installation of the first big show, ÔÇ£Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible,ÔÇØ and her thoughts, which mostly involve the shifting parameters of what it means that a piece is unfinished.

That Wagstaff et al. chose this theme, illustrated by works dating from 1437 to 2015, could be read as a gesture toward something like transparency (unusual for the Met) or even humbleness (even more so). But the first show also furthers an imperious claim: that the canon the Met has long seemed to embody is not a story with a fixed endpoint but one thatÔÇÖs ravenously open to┬áthe contemporary (a period, and market, that art patrons are ravenous for these days, and the Met has always been an academicized trove of billionaireÔÇÖs bling, so it has to stay with what it finds currently covetable). Although only about a third of the pictures are drawn from the MetÔÇÖs collection (six come from MoMAÔÇÖs), the exhibition shows off what Wagstaff has said all along the museum was planning: putting contemporary art in context, including the surprising influences on the later artists┬áÔÇö what you can learn from the imperfect.

She started with the Titian that opens the show (The Flaying of Marsyas, considered a bit underpolished for a Titian), stopping here and there to tell anecdotes. (Of a big blue Brice Marden: ÔÇ£He was very resistant┬áÔÇö well, reluctant,┬áto let us show this. But in the end he okayed it. So this is something that is absolutely unfinished. HeÔÇÖs kept it and kept it and kept it. He said he throws nothing away.ÔÇØ) ThereÔÇÖs a 1931 Picasso, probably of his mistress, although one canÔÇÖt be sure, since the face is violently squeegeed away. We pass a blue-and-burgundy Barnett Newman from 1970 which was considered incomplete because it needs another layer of blue paint (there are three of burgundy, but only two of blue), finishing up with the finale of the show: Cy TwomblyÔÇÖs Untitled I-VI (Green Paintings).┬áÔÇ£These have never been published or seen,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£They were painted in 1986 and Twombly designed the frames as well and theyÔÇÖre onboard.ÔÇØ He never allowed them out of his studio,┬áin Gaeta, outside Rome, and were never included in the catalogue raisonn├® of his works, published after his death, in 2011. ÔÇ£His partner, Nicola Del Roscio, didnÔÇÖt know why Cy had an issue with these; he felt they were finished.ÔÇØ

Twombly is credited with the idea for the show ÔÇöÔÇØ[I]t was important to me to be able to cite an artist for who came up with this idea,ÔÇØ Wagstaff says ÔÇö dating from when she was at the Tate and there was a retrospective of his work there.

The unfinished conceit is flexible ÔÇö possibly too flexible, and too encompassing, which makes the largely chronological installation feel a bit too abrupt at times, like youÔÇÖve turned the corner and wandered into a different and sometimes abruptly less-engaging museum show. Unfinished can mean abandoned mid-creation, because of the death of the artist (or the person paying for it), but more often the work is left a bit ragged or open-ended on purpose to achieve some stylistic or rhetorical point. Dodging art handlers (with their rubber suction cups) and donors getting sneak peeks during installation, Wagstaff, joined by┬átwo other curators responsible for the show, Kelly Baum and Andrea Bayer, told me those stories.

Pablo Picasso

Charnel House

1944ÔÇô45

On loan from MoMA, it is one of the pieces which Nick Cullinan had worked with Diana Picasso to get into the show (another being Woman in a Red Armchair) and it was completed at the end of the Second World War; it refers either to concentration camps (WagstaffÔÇÖs preferred interpretation) or to victims of a Franco massacre. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs incomplete and yet finished,ÔÇØ notes Baum, who joined the team in July. ÔÇ£You have a sense of the edits and corrections.ÔÇØ Picasso donated this painting to the Association Nationale des Anciens Combattants et Ami-e-s de la R├®sistance Francaise for an art exhibition in 1946. ÔÇ£He clearly considered it finished enough to donate; and then he called it back to his studio to, he said, make corrections. And then he sold it. We donÔÇÖt know if he made any corrections.ÔÇØ

Andy Warhol

Do It Yourself (Violin)

1962

Warhols do-it-yourself series marked the beginning of his move into fine art, and was based on then-popular Venus Paradise paint-by-numbers kits.* He made five of them, and only filled in one of them all the way. Its a finished painting of an unfinished paint-by-numbers kit, notes Baum. The task of completing the work was left to the viewer . Of course these works are now too valuable to allow that to happen.

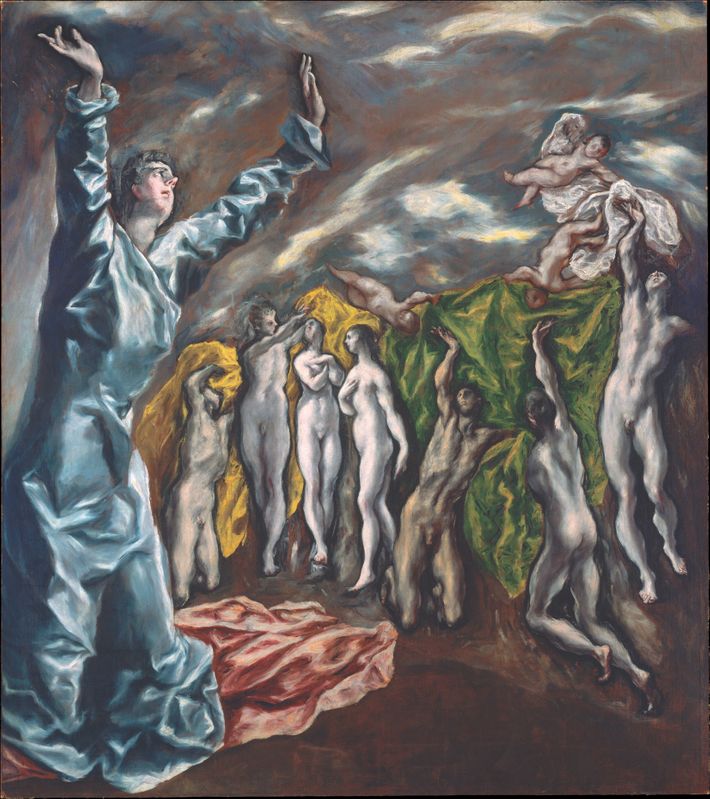

El Greco

The Vision of Saint John

ca. 1608ÔÇô14

This show is also a celebration of the Mets collection, says Andrea Bayer, a curator in the department of European Paintings. There are 26 or 27 paintings from the European Paintings collection including this El Greco. So one of the things which we hope is that it makes us look at old favorites in a different way: Its in a new building, and in a new context. Since its not on the wall of the Met, you can look at it as not a great masterpiece, but as a work which he didnt finish before his death. It was commissioned in 1608 for the altar of the Tavera Hospital outside Toledo. The man was gesturing to something. But it was cut off in the late-19th century  When it was rediscovered in the early-20th century by people like Picasso, who saw it while he was painting Les Demoiselles dAvignon, they were reacting to its unfinishedness, the fact that the people are floating and the ground is not defined and the sky hasnt been completely painted up.

Peter Paul Rubens

Henry IV at the Battle of Ivry

ca. 1628ÔÇô30

ÔÇ£This is a national treasure of Belgium,ÔÇØ says Bayer. At the time this was made, ÔÇ£Rubens was working in Antwerp,ÔÇØ and this was one of the paintings he was commissioned to do to document the victories of Henry IV of France for his widow, Marie deÔÇÖ Medici. ÔÇ£In 1631, he finds out that they had given him the wrong dimensions for this one, and were late paying, and so he just stopped.ÔÇØ The top of the picture, where his assistants were sketching out more of the battle, was cut off, while Rubens was at work on the center of the composition, which is a soldier with a fierce look on his face┬áÔÇö and three arms. ÔÇ£Rubens hadnÔÇÖt decided which armÔÇØ had to go, says Bayer.

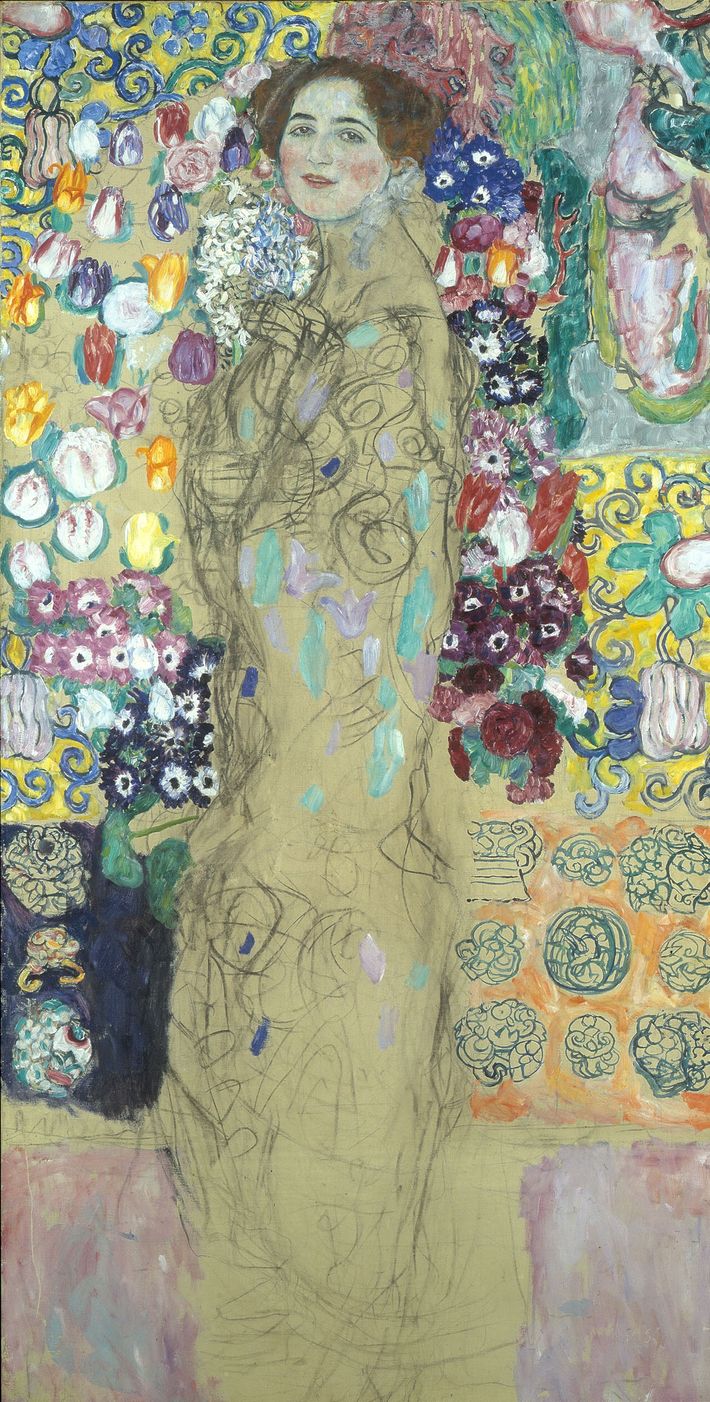

Gustav Klimt

Posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk III

1917ÔÇô1918

ÔÇ£This is a posthumous portrait of a woman who killed herself over a love affair,ÔÇØ says Baum. Maria ÔÇ£RiaÔÇØ Munk was the niece of a major patron of KlimtÔÇÖs, and the writer Hanns Heinz Ewers broke off their engagement. ÔÇ£Her family asked [Klimt] to make it, but he couldnÔÇÖt get it right. They werenÔÇÖt happy with it and he did it again and again. And he died with it on his easel.ÔÇØ

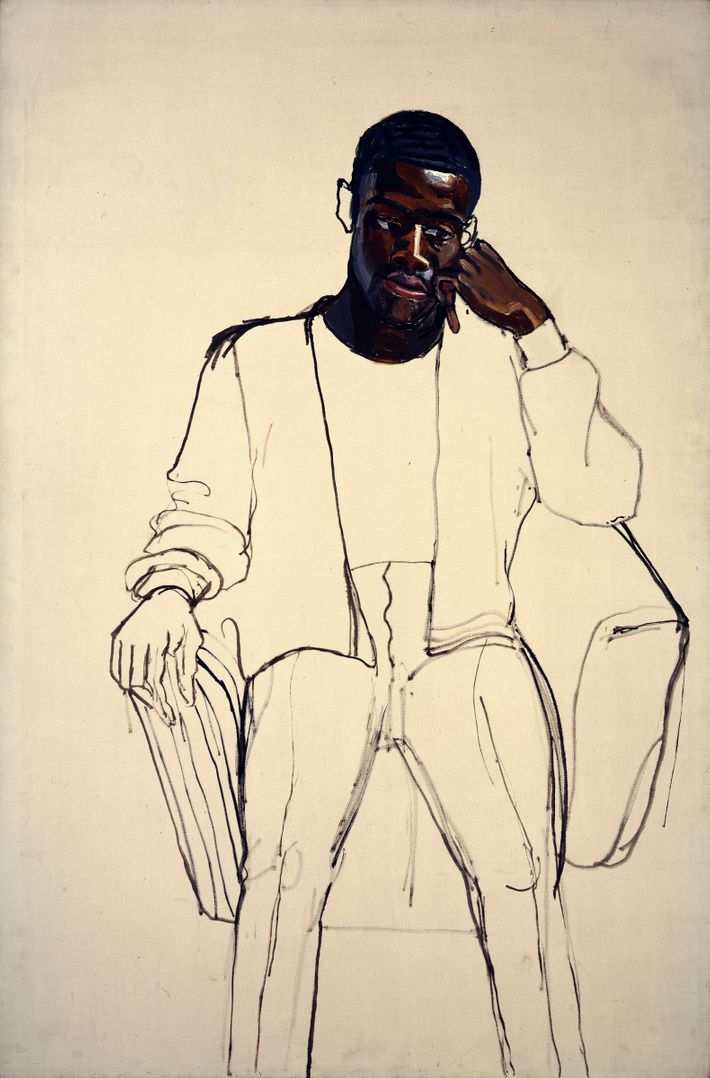

Alice Neel

James Hunter Black Draftee

1965

ÔÇ£She would ask people she didnÔÇÖt know off the street to come in and sit for her,ÔÇØ says Baum. ÔÇ£She asked this man James Hunter to pose and he told her he had been drafted for the war. He never came back for his second sitting. She decided she was going to call this painting finished anyway. She signed the back and showed it in the Whitney here in her retrospective in 1974. We donÔÇÖt think he died because his name is not on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in D.C. But we donÔÇÖt know what happened to him.ÔÇØ

James Drummond

The Return of Mary Queen of Scots to Edinburgh

ca. 1870

ÔÇ£He is a Scottish artist working in a very traditional manner,ÔÇØ says Bayer. ÔÇ£We think he stopped because the panel cracked.ÔÇØ It shows DrummondÔÇÖs methodical approach to painting: Some parts are complete (notably the architecture and some of the costumes), but other parts, including MaryÔÇÖs face, are little more than graphite underdrawing. A finished version of the same scene, on canvas, is today at the National Galleries of Scotland.

Anton Raphael Mengs

Portrait of Mariana de Silva y Sarmiento, duquesa de Huescar

1775

ÔÇ£The collector Otto Naumann has a personal interest in the incomplete: He is out there looking for unfinished works of art,ÔÇØ says Bayer. Naumann also loaned the show this one. Mengs was a very prominent painter of his time┬áÔÇö┬ápapal commissions and so forth┬áÔÇö┬áand it isnÔÇÖt clear why this wedding portrait wasnÔÇÖt finished. ÔÇ£ThereÔÇÖs the ring, and that would be the faithful dog,ÔÇØ Bayer points out, before noting that it was either never painted or scraped out. [The subjectÔÇÖs] face looks blurred out, as if sheÔÇÖd gotten caught on a reality-TV-show shoot and refused to sign her waiver. It kind of reminds you of a John Baldessari.

*This article has been corrected to show that WarholÔÇÖs Do It Yourself (Violin) was not part of his show at Sable Gallery.

*A version of this article appears in the March 7, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.