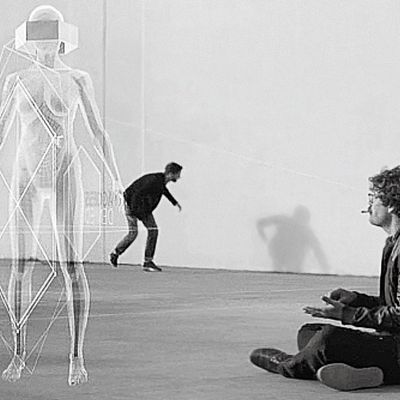

Benjamin Dickinson’s cheeky, ultrachic sci-fi comedy Creative Control turns on the concept of augmented reality, delivered here via a pair of eyeglasses that enable the wearer to capture, manipulate, and enhance the image of anything or anyone. The wearer is David (played by Dickinson), a trim, bearded, Williamsburg-based adman who uses a pill to rev himself up on his way to the office, Scotch to ease himself down before bed, a smokable anti-panic drug called Phalinex, and a personal digital assistant to keep him feeling connected to the rest of the world. The glasses — on loan from a client called Augmenta — look to be the ultimate way to bend reality to his will. When he can’t bring himself to put the moves on his best friend’s girlfriend, Sophie (Alexia Rasmussen), he surreptitiously uses his glasses to scan her form and checks into the Wythe Hotel — away from his own live-in girlfriend — to get to “know” her better. You might say that David attains creative control at the expense of, well, his soul.

Working in a crisp, clean black and white, Dickinson creates a future in which the shells of cell phones and tablets are nearly transparent, so that their text and images seem suspended in the air, in clear-partitioned offices in buildings made of glass. When Dickinson splits the screen, the effect isn’t jarring: It’s an extension of a space that seems infinitely subdividable. The whole world is composed of invisible partitions. In one shot, the jittery, drug-addled David navigates a screen on which multiple people text him with increasing urgency while, via a video link, the Augmenta commercial designer (fuzzy-maned Williamsburg hipster Reggie Watts, as Reggie Watts) babbles about multiple, convoluted realities. David is at once “plugged in” and far away. He resembles the dangerously (to women) indecisive title character (skewered from the inside) of Adelle Waldman’s novel The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. But he’s a Nathaniel P. whom technology has taken to a disturbing new level of solipsism.

Dickinson is too cool to spell out a message, but Buddhists, 12-steppers, and sundry anti-materialists will tell you (at length) how the hunger for control is the shortest path to enslavement. The connections among addiction, high-tech virtual reality, and the purgatory of solipsism put Creative Control in the slipstream flowing from Philip K. Dick, while a preference for artificial life forms over humans links the film to the recent Her. Antonioni’s masterpieces of alienation are somewhere in the artistic stew, but Dickinson (along with cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra, production designer John Furgason, and Parisian visual-effects studio Mathematic) makes their inorganic universe all of a piece. The soundtrack, full of baroque chestnuts, adds an extra layer of irony that the movie might not need, but it creates a lovely counterpoint to the abrasive, sadomasochistic fashion photography of David’s pal Wim (Dan Gill). The thing to hang on to is that we humans are already framing reality to suit our whims and fetishes. The foundation of Creative Control’s future is already here.

Dickinson finds a place for a different, more wholesome sort of reality too. David’s girlfriend, Juliette (Nora Zehetner), is a yoga instructor, helping students to adjust their bodies to create a fluid path to cosmic oneness. Increasingly high-strung and uncentered, Juliette takes another lover but has a mystical vision of David’s face atop his — a sign, she maintains, of her and David’s connection. Is this vision meant to be genuine, really real, or the fruit of another sort of drug? Creative Control is the most elegant vision imaginable of a world in the process of losing its moorings.

*This article appears in the March 7, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.