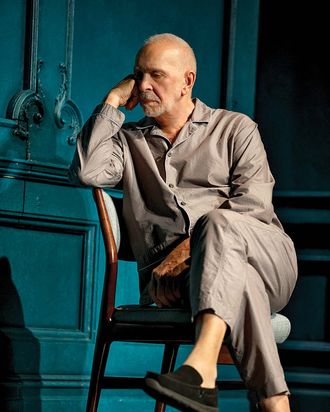

All stage stars seduce their audiences, but how? The winkers do it coyly, the vamps brazenly, the intensos while pretending not to notice you are there. The slightly kinky way Frank Langella does it may remind you of a ravishment: You’ve come into his lair, and he’s going to have you however he wants. There is a great deal of technique behind it, and a bristling alertness to the theatrical moment, but also a whiff of disdain, the seed of which is need. In 40 years of watching Langella onstage, from Seascape and Dracula in the 1970s through Frost/Nixon and Man and Boy just recently, I’ve never seen that need come as close to full exposure as in the just-opened Manhattan Theatre Club production of The Father — not to be confused with Strindberg’s play of the same name, which Langella headlined at the Roundabout in 1996. In this Father, the American debut of the young French playwright Florian Zeller, Langella gets so close to strip-mining the core of his gifts that you think he may cave in, or that you will. It’s a must-see performance.

The Father, though, is only a might-see play, more of a vehicle than a destination. Langella stars as André, an 80-year-old man who, though physically vigorous and charming when he wants to be, is steeply declining into senile dementia. Zeller’s trick — a good one, but still a trick — is to make the audience experience his dementia as if from inside. When the play begins, André’s daughter Anne is explaining to him that she has to find a new “helper” because the last one quit after he called her “a little bitch” and threatened her with a curtain rod. André at first denies this, then laughs it off, saying he is perfectly competent to care for himself. But when Anne appears in the next scene, he doesn’t recognize her. Nor do we: She is played by a different actress. And though our confusion is quickly resolved once we understand the playwright’s gambit, André’s only grows. People keep stealing his watch. A strange man hits him. Furniture disappears as quickly as biography. In younger years, we variously learn, André was an engineer or a clown or a tap dancer. (Langella’s gleeful attempt at a dance routine is heartbreaking.) And Anne’s story keeps changing, too. Sometimes she is a divorcée moving to London; sometimes long married and staying put. “Make up your mind!” André eventually complains, but we know it’s his that’s in trouble.

Over the course of 15 taut scenes, shuffled in time and punctuated by blinding flashes of light that suggest synaptic misfires, the confusions of André’s Alzheimer’s become calamities. It’s bad enough that his memory decomposes; eventually his personality does too. Langella’s physique — he’s a ramrod six-foot-four — makes his descent from haughty authority into second childhood all the more pathetic; he can hardly fold his whole body up to be comforted, babylike, with a pat and a shush. Even so, this wonderful effect eventually seems to clash with the intentions of the playwright. Zeller calls The Father “a tragic farce,” and apparently that’s what it was when it opened as Le Père in Paris in 2012. The great French actor Robert Hirsch, at 87, looked noticeably frailer than the strapping, 78-year-old Langella does now; perhaps André’s decline was proportionally less surprising and thus less devastating. But even without that, the play, at least as translated by Christopher Hampton for its British premiere in 2014, is noticeably cool to the touch, a chic arrangement of diminishing effects. Of the two genres promised, it offers more of the pleasures of farce than those of tragedy. It’s more “How does this all fit together?” than “Why does this all fall apart?”

Despite retaining the Paris setting — the costumes by Catherine Zuber pinpoint the city and social class exquisitely — the director Doug Hughes pushes hard against Zeller’s neat contraption. There is laughter but nothing farcical about this production. The walls of Scott Pask’s set are a rich and somber cobalt; the lighting by Donald Holder is high contrast, with the dark always creeping in. The interstitial music by Fitz Patton sounds like the inside of a hundred cellos. But it’s the emotional temperature of the acting that makes this Father feel more American than its bare script does. Langella, who in some plays threatens to devour everyone else onstage, is here well matched by a cast of actors who perform their own seductions and know how to find their light. Especially effective are Kathryn Erbe, as Anne, on whom the bulk of the struggle falls, and Hannah Cabell, bright and unflappable and then taken for a ride as one of those doomed helpers. The question of who can benefit from help in a situation like André’s is not a deep one, but it’s universal enough to make The Father a savvy French import, like Brie.

Still, the play defies logic at times. Some of its effects depend on the unlikely obtuseness of characters who presumably have prior experience dealing with dementia. Telling a patient “You ought to remember it by now” is probably not best practice in Alzheimer’s care. When the once-punctilious André asks the time, one helper unhelpfully answers, “Time for your medication.” No one seems to understand or credit the man’s wounded pride and terror. Perhaps this is because we are still meant to see the story through André’s consciousness: He thinks he’s being gaslit. Even so, the central conceit gets dodgy by the sixth or seventh scene. Not only have we caught on sufficiently that it no longer produces much disorientation, but Zeller seems to lose track of it himself, playing cognitive tricks even in scenes that André isn’t part of. So what does the conceit mean now? Does the play have Alzheimer’s? Do we?

That would be an odd moral, but contemporary French plays — even winners of the Molière Award, like The Father — have a habit of privileging formal wit over profound insight. (Among the few Paris imports seen on Broadway recently are Yasmina Reza’s trio of Art, Life (x) 3, and God of Carnage: each high concept and low impact.) American plays usually default in the opposite direction. But if The Father gets only partway across the ocean on its own steam, Hughes has tugged it near to shore, and Langella, that roué, docks it every night. What he does to the play is almost as pleasurable and improving as what he does to the audience.

*This article appears in the April 18, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.