This piece originally ran in May of 2016 when Captain America: Civil War hit theaters. We are republishing it on the occasion of The Falcon and the Winter Soldier’s premiere on Disney+.

Superheroes are generally a static bunch. A character gets introduced, a little bit of tweaking might occur in early stories, and once it’s a hit, it gets frozen in amber. Spider-Man is always wise-cracking and angst-filled Peter Parker, Wolverine is always a grizzled brawler with a tragic past, and so on. Superman may have “died” in 1992, but he soared up from the grave within a few months. Bruce Wayne was replaced as Batman in 2008, only to take up the cape and cowl again in a few years. There’s an old saying in the comics industry, often attributed to former Marvel chief Stan Lee: Readers don’t want change; they only want the illusion of change.

But one character, by his very existence, reveals the folly of that mind-set. Bucky Barnes, now known in print and onscreen as the Winter Soldier, was first introduced in 1941 as Captain America’s plucky teen sidekick. Since that time he’s undergone not one but two enormous changes, both of which fundamentally altered the Marvel universe’s status quo. First, he was killed off in 1964 and actually stayed dead — for four decades, at least. Then, in 2004, he was brought back in a thrilling comics story line and given the nom de guerre “Winter Soldier.” The resurrected version of the character abandoned his boyish roots, instead taking on a tragic narrative cooked up by a tiny cabal of nervous creators and editors. The story was a surprise hit, and this new vision of Bucky became the one seen in 2014’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier and now Captain America: Civil War. In a world where film has usurped comics as the medium of record for superhero fiction, Bucky’s reinterpretation has not only succeeded — it has become gospel.

Given that Civil War’s other stars are all characters that ossified soon after their own births, Bucky’s reinvention is no small feat. The Winter Soldier has resonated with people because his archetype is a heady brew of mental-health struggles, classic espionage tropes, America’s poor treatment of veterans, an attempt to reckon with the violence of superhero comics, and male bonding so powerful that it’s regularly read as homoerotic. The tale of Bucky and the comics story that changed him is one that shows superhero fiction’s unique power to play around with characters created far in the past, and demonstrates how gratifying — and profitable — it can be to come up with one little idea that takes a hard left turn away from orthodoxy.

***

Ironically, Bucky’s creation three-quarters of a century ago was all about orthodoxy. In 1941, three years after the first superhero comic was published, two pioneers of the nascent medium, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, were cooking up a new crime-fighter: Captain America. He was intended to be an expression of national wish-fulfillment: In a time of American dread about the possibility of entering the morass in Europe, he would leap into the fray and clobber Hitler before the madman could threaten our shores. But triumph in war was one thing; triumph in the marketplace was another. To make it big, Cap would need something that was all the rage: a kid sidekick.

Such characters were a useful invention for an array of reasons. “Superhero comics were seen as having an audience of kids,” says Peter Sanderson, comics historian and former Marvel writer. “So the idea was, Let’s give the kids someone to identify with.” The first hit sidekick was Robin, the young ward of Batman, who leapt into action in 1940. The boy wonder sparked an immediate craze. “It helps humanize the adult superhero due to the fact that he gets along with a kid,” Sanderson adds. “And you have a story device that means you don’t need captions to explain what the hero is doing. He can explain it all to his sidekick.”

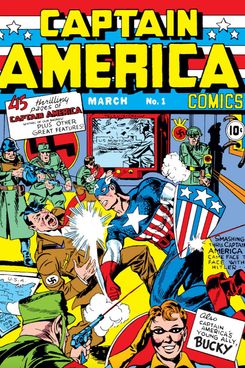

And so, when Captain America Comics No. 1 rolled off the presses in January 1941, a youthful companion, Bucky — named somewhat arbitrarily after a high-school classmate of Simon’s — was right there on the cover. Beneath the now-famous image of Cap landing a haymaker on the führer’s chin, you could see an auburn-haired youngster with ruddy cheeks and a domino mask saluting you. Above him, handwritten text read, “Also CAPTAIN AMERICA’S YOUNG ALLY, BUCKY!”

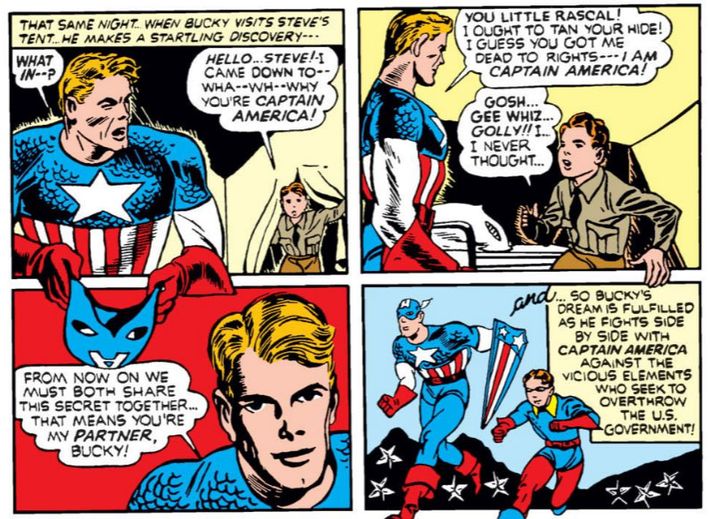

Much of the issue’s action takes place at New Jersey’s Camp Lehigh, where flaxen-haired grunt Steve Rogers lives a secret double life as super-soldier Captain America. On page seven, we meet “Bucky Barnes, mascot of the regiment,” who waxes poetic about his admiration for the star-spangled hero — and then accidentally wanders in on Steve getting into costume. “I came down to — wha — wh — why you’re Captain America!” he cries. “You little rascal! I ought to tan your hide!” Cap says in response. With bizarre abruptness, Steve opts for comradeship over corporal punishment. “From now on we must both share this secret together … that means you’re my partner, Bucky!” With that (and without explanation), Bucky suddenly gets his own colorful getup, complete with red tights and impractical blue boots.

For the next few years, they took on all who would threaten the Republic, especially the domestic boogeymen of Nazi spy rings and dangerous fifth columnists. Bucky was relentlessly optimistic, only pushing back against his older-brother figure when he felt condescended to. “Think you can handle a man’s job … Bucky, m’lad?” Steve asks in one story. “Sure I can — what do you think I am — a baby?” is the kid’s reply. The comics were runaway hits for their publisher, Timely. But the first superhero bubble popped after the end of the war. Other genres usurped it: crime fiction, Westerns, and horror. Sales of Captain America’s series declined. As a triage measure in the late ‘40s, the publisher experimented with targeting young women and, as such, sidelined Bucky in favor of new Cap sidekick Golden Girl. Even she couldn’t get the job done. Captain America Comics ceased publication in 1949.

There was an extremely short-lived attempt to revive Cap and Bucky as anti-communist crusaders in 1954, but it, too, failed to find an audience. Bucky and his beloved mentor were unceremoniously tossed on the trash heap of pulp history. Then, a decade later, something remarkable happened: In the early 1960s, writer/editor Stan Lee and writer/artist Jack Kirby (back at the company after an exile) relaunched Timely as Marvel Comics, with the goal of completely reimagining what superheroes could be. As part of that process, they eventually turned their focus toward Captain America — and Lee didn’t like what he saw by Cap’s side.

“One of my many pet peeves has always been the young teenage sidekick of the average superhero,” Lee wrote in his 1974 book Origins of Marvel Comics. “Once again, if yours truly were a superhero there’s no way I’d pal around with some freckle-faced teenager. At the very least, people would start to talk.” In Lee’s mind, the only teens worth writing were ones who were powerful in their own right, with loner hero Spider-Man being the best example. When it came to Bucky, that philosophy had major consequences.

In 1963 Lee and Kirby launched The Avengers, a series that would bring together some of Marvel’s biggest characters to tackle the world’s most serious threats. Issue four featured a startling cover image: Captain America leaping into battle alongside the previously introduced Avengers. The first page read, “BRINGING YOU THE GREAT SUPER HERO WHICH YOUR WONDERFUL AVALANCHE OF FAN MAIL DEMANDED.”

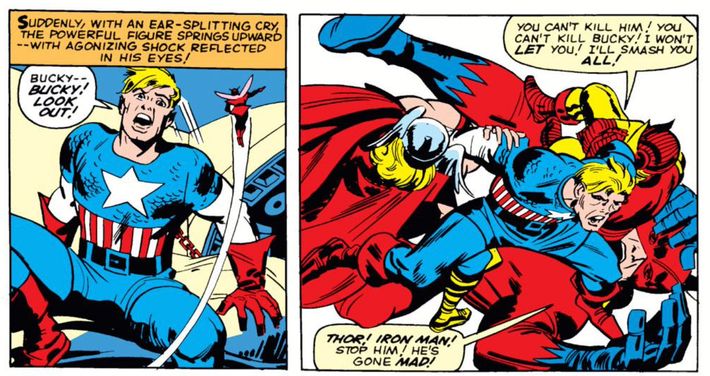

Sure enough, the book revealed that Cap was back — and, improbably, just as youthful as he’d always been. In the story he’s found trapped in ice in the North Atlantic, and, upon thawing out and waking up in front of the heroes, he jolts up and screams, “Bucky — Bucky! Look out!” But there’s no Bucky to be found. As we learn in a flashback, tragedy struck during the war: Bucky was blown up while trying to stop a booby-trapped plane in midair, and Cap — attempting to save him — fell into the frigid water, where he froze in suspended animation, only to later wake up in a world where his best chum was long gone.

“It’s useless!” Cap screams as Thor and Iron Man try to comfort him. “He is dead — he is! And nothing on Earth can change that!” For the next 40 years of Captain America stories, the death of Bucky resembled the death of Bruce Wayne’s parents or Peter Parker’s Uncle Ben: a personal tragedy that haunted the protagonist. The long-dead sidekick didn’t motivate Cap to get into crime-fighting — he’d been down for the cause well before the two of them met, back in the 1941 origin story. But he certainly wanted to do his erstwhile buddy proud, and the kid’s absence reinforced Cap’s status as a man out of his time. (It’s a somewhat goofy thing to read about now, given that the average World War II vet was only in his 40s as of the mid-’60s — he certainly had plenty of war buddies who weren’t that far gone, no?)

Throughout the ensuing decades there were still stories starring Bucky, but they were strictly World War II flashbacks. His earnest enthusiasm served as a reminder about Greatest Generation optimism and certainty of purpose — thus making him a relic in an era where the Vietnam War was shattering American confidence in military might. Occasionally, young characters would try to become new Buckies, to no lasting avail. A 1969 tale crafted by Lee and writer/artist Jim Steranko featured perpetual Avengers hanger-on Rick Jones presenting himself in Bucky’s old duds. “No!” Steve yells, forcefully grabbing him. “You can’t wear it! No one must ever wear it! I’ll never watch another partner die!”

In other words, though Bucky was gone, his memory lingered. But any attempt to revive him in the present day was an axiomatic no-no. According to Sanderson, while he was working at Marvel in the 1980s, “one of the absolute rules at Marvel was, the two characters who were absolutely, permanently dead — and there was no way they’d ever come back — were Uncle Ben and Bucky.” But superhero comics is an industry that thrives on big, weird ideas. Around the turn of the millennium, a new guard was in charge, and they were willing to engage in the heretical dark art of resurrection.

***

Ever since he was a kid, comics writer Ed Brubaker felt like Bucky was the victim of a great injustice. Born in 1966, Brubaker spent much of his childhood in Guantánamo Bay, the child of a Navy intelligence officer, reading and relating to stories about Cap’s sidekick. “I was a Navy brat, and he was an Army brat,” he says of Bucky. He’d assumed there was some kind of long, dramatic story in which Bucky had been killed off, a story he just hadn’t dug up yet. Then he learned the death was tossed off in a single page of The Avengers No. 4. “I was a 9-year-old kid,” he recalls, “and I was horrified.”

A creative child, Brubaker wasn’t one to take this crime lying down. If Bucky had been killed without much ceremony, he felt a nice corrective would be to resurrect him and let him have his day. “From the time I was probably 9 or 10 years old I kept, I was in my sketch books, plotting out ways to bring Bucky back,” he says. One solution? Mix him up in some Cold War intrigue.

“I think the idea that Bucky was captured by the Russians and used as an enemy against America was something that I came up with during the Cold War as a little kid in the mid-’70s,” he says. “Even as a kid I had a good sense of dramatic structure, apparently. I knew that if you were going to take away Cap’s biggest tragedy you had to replace it with another huge tragedy, or he would lose that marble for you to play.”

Flash forward to the early 2000s. Marvel Comics was in a chaotic renaissance. After the comics industry collapsed in the mid-’90s and Marvel went bankrupt, new leadership had pulled the company back from the brink through a series of experiments in different ways to tell stories, both narratively and visually. New writing talent with limited superhero experience was being brought in all the time. Against this backdrop, in 2004, Brubaker — previously best known for writing crime stories — was recruited to write a relaunched Captain America monthly series alongside penciler Steve Epting. Brubaker brought with him the idea of doing a story that would bring back Bucky using some of the Russian intrigue he’d cooked up in his childhood.

Lucky for him, the notion of reviving Bucky was already kicking around in the innovation-hungry ecosystem of early-aughts Marvel, though not everyone was onboard. “A previous creative team pitched the idea of bringing Bucky back, and I was dead set against it,” says Tom Brevoort, then editor of Captain America. “It was something that [Marvel editor-in-chief] Joe Quesada and I discussed, in a conversation that got louder and louder as we both became more impassioned, until we were literally yelling at one another in this meeting. In that case, the story didn’t end up going forward — but it was an idea that held some appeal for Joe, and so he brought it up when speaking with Ed.”

Brubaker had to pass the gauntlet of Brevoort’s skepticism. How did he survive that explosion on the little plane, Brevoort asked? Brubaker said he’d fallen into the water — grievously injured, missing his left arm, and suffering from amnesia — and was rescued by a Russian officer, who subsequently used him as a black-ops assassin. Why can’t he remember what happened to him? Brubaker proposed that, every time Bucky started getting inklings of his past life, the Russians put him in suspended animation (and hey, that also answered the question of why Bucky wasn’t an old man by the aughts). Brevoort recalls asking 14 queries in total, forcing Brubaker to tighten up his approach.

The story in which Bucky would come back would be called “The Winter Soldier,” a title that alludes to the fraught relationship the U.S. has with its veterans. In 1776, Thomas Paine published the first installment in a series of pamphlets called The American Crisis. In it, he decried the “summer soldier” who “will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country.” Two centuries later, Vietnam Veterans Against the War referenced Paine when they staged a 1971 event called the Winter Soldier Investigation, during which they drew attention to the immorality of America’s actions in Southeast Asia. A young John Kerry spoke there, giving an incendiary testimony about what America was doing to its drafted men. “The country doesn’t know it yet, but it has created a monster,” he said. “A monster in the form of millions of men who have been taught to deal and to trade in violence … men who have returned with a sense of anger and a sense of betrayal which no one has yet grasped.”

This sentiment would lie at the core of what Brubaker was going to try to talk about with Bucky. “It’s just one of those names that, the second I wrote it down, I didn’t have any alternates,” Brubaker recalls.

The resulting story, launched on November 17, 2004, was a cracking espionage yarn. In the first few issues of Brubaker and Epting’s run on Captain America, a string of mysterious murders and attacks start occurring, all tied in one way or another to Cap. A government agent theorizes they might all be coming from a Cold War–era Russian assassin only known as the Winter Soldier. Meanwhile, Cap reminisces about World War II, and his reveries include a shocking revelation about Bucky: Although the boy was held up to the public as a symbol of youthful pride in America, he was secretly sent out to viciously execute enemy soldiers as an advance scout during attacks. He was a weapon as much as he was a mascot.

Brubaker — the son of a soldier — made that storytelling choice as a corrective to the sanitized version of the war that so often appears in superhero comics. “I wanted to take World War II seriously,” he says. “If this guy fought in World War II, what good would he have been if he wouldn’t actually do the same things that any other soldier had to do?”

Then came May 25, 2005, the day when issue No. 6 would reveal the Winter Soldier’s identity. “I was terrified that that was going to be the end of my career,” Brubaker recalls. “My fear was that people would think we’d jumped the shark or something.” It wasn’t an unreasonable fear. Previous status-quo-shaking comics events had marred sales and reputations — for example, there was a widely mocked ‘90s tale about Spider-Man being revealed as a clone, and none of its creators emerged with their names unsullied.

No. 6 hit stands, and, on page 17, readers got their first clear view of the Winter Soldier, his rifle trained at Captain America’s head. A friend of Cap’s who’d been captured by this mysterious figure tells our hero, “I think — I think it’s Bucky!” The man had long, brown hair — a request Brubaker says came from Quesada, who wanted to make it clear that Bucky wasn’t a kid anymore. He had a bionic arm with a Communist red star on it — Brubaker and Epting were tapping into the tradition of comic-book pseudoscience. And, lest we forget that he was still Bucky at his core, he had that classic little domino mask on. A reinvented icon had arrived.

The next few issues included flashbacks explaining his rescue at the hands of the Russians, his decades of assassinations and suspended animations, and Steve’s first face-to-face meeting with his former ward. That latter scene is agonizing for Cap. “Bucky … ?” Cap says during a battle. The Winter Soldier gazes directly at him and asks, “Who the hell is Bucky?” An explosion hits, and the brainwashed man is gone. Cap grits his teeth and, in a debriefing, smashes a computer screen in anguish.

The whole endeavor was a hit. The issue with the Bucky reveal went to a second printing, and sales for the ensuing issues were robust. Editorial leadership loved how it had played out. The fan community was abuzz about this new direction. Most important, the saga was genuinely compelling. Cap no longer had to grieve over Bucky’s death; instead, he now had to grieve over his life. For all these years, Bucky was walking around, being forced to commit unspeakable acts. “He’s not responsible for his actions … not in control,” Steve muses about Bucky at one point. “He’s not in control … and he’d hate that more than anything.”

Steve later encountered Bucky again and used a magic device to make his original identity and memories come back, but since he still remembered everything he did while brainwashed, that act caused as much pain as it removed. Bucky goes on the run, tormented by what’s in his head. “Some small piece’a you is awake … watching,” he says in one comic, remembering all of his crimes. “Like being a passenger in your own body. You struggle to break loose. Over and over again … you lose. And it makes whatever you’re forced to do that much worse.”

In other words, Bucky’s story was one about violence, following orders, and PTSD. Even if he wasn’t the one calling the shots, it was his body, his face, and his skills doing the killing. It was him who saw lives end at his own hand. How could he ever get over that mental damage? The character — an emotionally vulnerable bundle of grief, anger, and deadly efficiency — was here to stay. At the end of a big story that had nothing to do with Bucky, Steve Rogers gets killed, and soon afterward Bucky reluctantly takes up the shield and becomes the new Captain America. He struggles to live up to the role and continues to grapple with the fact that killing and espionage feel so comforting to him.

Steve comes back from the dead and eventually becomes Captain America again — further proof that, more often than not, characters’ status quo never changes for long. But Bucky never went back. To this day he has the metal arm, he has the long hair, the troubled past, the PTSD — it’s all there. On top of that, the nature of the Captain America archetype has changed. His empathy for and regret-filled friendship with Bucky, elements totally absent for 60-odd years, are now defining traits for the Star-Spangled Avenger. It’s a gut-wrenching narrative — and as the Marvel Cinematic Universe took root during the late 2000s, a pair of screenwriters took note.

***

In 2008, after being hired to script a Captain America movie for the nascent Marvel Studios, Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely tried to read every iteration of the character. One era stood out among all of the others. “Brubaker’s was maybe the finest run,” says McFeely. The movie they were writing was set almost entirely in World War II, so their Bucky couldn’t be a cybernetic super-assassin, but their mouths watered at the possibilities, even as they tried to manage their own expectations. “We didn’t dream that we would have sufficient success to get around to doing a Winter Soldier story,” says Markus.

That movie, Captain America: The First Avenger, came out in 2011 and featured up-and-comer Sebastian Stan as Bucky. The movie deviated from the comics version of the character by making him a childhood friend of Steve’s — one who not only wasn’t a child, but was actually a big-brother figure to our hero before the super-soldier experiment. (Part of the reason for the change was their feeling that, as Markus puts it, “there’s just no way, even in a stylized movie, that you can bring an 11-year-old into World War II.”) Nevertheless, the pair have an incredibly close relationship during the war, and, as in the comics, Bucky seemingly dies during a risky mission, wracking Steve with grief. The movie was a success, and Marvel Studios immediately set in motion plans for a sequel. Markus and McFeely had their chance.

“We knew we wanted to do some version of Winter Soldier,” Markus says. “There was some talk of, Maybe it’s too soon — he only just died. But as we went through various iterations, it was still the most compelling action story to tell.” Beyond espionage thrills, a Winter Soldier story could also get at some weighty themes for a tentpole superhero movie. “It is, in a comic-book way, a way of exploring the price soldiers pay and what we do with them when they’re done,” Markus says. They sent a bunch of story ideas to the higher-ups at Marvel and got approval to move forward with a Winter Soldier tale.

And so, an idea that began with Brubaker’s childhood scribblings was produced on a $170 million budget and pushed out to audiences worldwide. In the spring of 2014, Captain America: The Winter Soldier hit screens. It was a smash. The story was an extremely loose adaptation of the Brubaker and Epting comics, but the major story beats were there: The mysterious, lethal metal-armed Winter Soldier starts knocking off people close to Cap; we learn that he’s been a black-ops agent for decades (here, he’s owned by a sinister organization called Hydra rather than the Russian government); Cap figures out he’s Bucky; they fight; Cap forces Bucky to remember who he is; and Bucky goes on the run, torn apart by confusion and regret.

Despite being one of the title characters, Bucky has fewer than 20 lines of dialogue in the whole movie; even so, he struck an emotional chord with viewers, galvanizing a burgeoning community of Marvel-movie fans. “When he appears in the Winter Soldier, I was fascinated even before his identity is revealed,” says Lisa Henning, an avid member of online Bucky fandom. She loves Bucky-oriented fanfiction and fan art, and she makes videos on her YouTube channel that remix footage of Bucky and Steve with emotional music behind them. “He seemed like a sharp, precise killer machine with no concept of mercy, so the reveal who he really is was a great moment. What really got to me, though, was the way Sebastian played him as scared, confused, and vulnerable after he encounters Steve.” (Enthusiasts have also built up a considerable bank of material dedicated to depicting a romance between Steve and Bucky, or “Stucky,” as the pair is known.)

The fandom will find a lot to enjoy in Civil War. Even though his name isn’t in the title, the Winter Soldier is a much more prominent character than in the previous Captain America outing. We see him on the run from the world’s governments, we see Cap turn against his colleagues in the Avengers in order to protect him, and we see him struggle with his past. Stan gives a performance that is by turns lethal and heartbreakingly tender. “I can’t trust my own mind,” he says at one point with a sad half-smile. If you’ve suffered a trauma and had to contend with the mental-health issues that follow, you’ll likely feel a pang of melancholic recognition.

But for historians of superhero fiction, the movie’s depiction of the Cap-Bucky relationship is perhaps most interesting on a metafictional level. This Captain America, played with Chris Evans’s usual charm and earnestness, is more or less the same Captain America who leapt into battle against the Third Reich 75 years ago. This Bucky, however, is wildly different from the one who leapt beside him all those decades ago. And yet, as you can see in Stan’s performance, that optimistic scrapper is somehow still a part of the character. Steve remembers his pal’s more innocent days and wants him to remember that he hasn’t lost all of his virtue. A lesser story would show them as rivals; this one shows them trying to rebuild a friendship, piece by piece.

That dynamic was baked into this new Bucky way back in 2004. Brubaker doesn’t work for Marvel anymore, opting instead to do acclaimed independent comics like The Fade Out and Velvet. But he looks back at those consequential comics with pride, as much for what they didn’t do as for what they did. “I didn’t want to play it like a ‘You never came looking for me, so I hate you’ kind of thing,” he says. “I wanted it to feel more tragic than it being that they were two trains racing at each other. It wasn’t a revenge story. It was a redemption story.” And it remains a story unlike any other that comics have told.