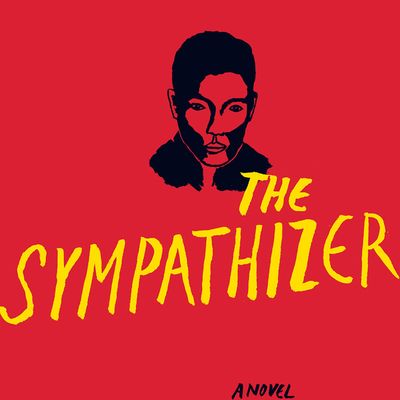

Last week, the Mystery Writers of America handed out the 2016 Edgar Awards, the most prestigious of the crime-writing awards. Among the winners was The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen, named Best First Novel — a win that, while well-deserved, was the opposite of notable, given that his novel has already garnered a host of accolades, including the Pulitzer Prize the week before. And yet, for this exact same reason, his Edgar win is remarkable, even momentous — and likely unprecedented. The Sympathizer — a literary thriller about a Vietnamese double agent who moves to Los Angeles after the Vietnam war — is the first novel (or at least the first I can unearth) that’s won both a major literary award and a major genre award in the same year.

The cross-pollination of “literary” fiction and “genre” fiction has been a hot subject of contention for years in bookish circles, “a lover’s quarrel among literati,” as critics, both online and off, bandy questions like What exactly constitutes a genre book? and Can genre books be truly literary? and Are genre and literary books even comparable? The debate has persisted for so long that many declare it over, irreconcilable, or misguided, and yet, within the most august critical citadels, there’s a persistent resistance to the idea that these types of fiction might be regarded on anything like equal footing. Awards — the arbitration of which is notoriously contentious and prone to human foibles — are certainly not a foolproof instrument for the purposes of enriching, let alone settling, this debate. And yet, when a novel does what The Sympathizer accomplished — i.e., something that’s never happened before in roughly 100 years worth of book-award-giving-outing — it’s worth asking why this has never happened before, and why it happened now. The accomplishment of The Sympathizer suggests we may have finally achieved the Great Literary Convergence — that moment when all novels, of all stripes, and all genres, are finally considered, if not identical undertakings, than subsets of the same, larger, expansive literary project.

But first, to the awards themselves. For the purposes of my quick, scrap-paper census, I looked back through the history of the most prestigious crime award (the Edgars); the two most high-profile science-fiction awards (the Hugo and the Nebula), and the two most prominent literary awards: the Pulitzer and the National Book Award. I asked Sarah Weinman, an expert in the history of crime fiction, if Nguyen’s feat had a precedent: She told me she couldn’t think of one, though, in 2006, Jess Walter’s Citizen Vince won an Edgar for Best Novel and his next novel, The Zero, was shortlisted for the National Book Award.

I thought, for sure, there must be previous double winners in the annals of fiction — yet looking back through the history of these awards, I found only a litany of close calls, near-misses, and should-have-beens. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, for example, was a finalist for both the National Book Award and the Hugo in 1970, but won neither. More recently, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven made the National Book Award shortlist, won Britain’s Arthur C. Clarke award for science fiction, and received an endorsement for the Hugo award from no less an eminence than George R.R. Martin.

Of course, part of the rationale for genre-specific awards is to recognize excellence in fields of writing that are traditionally excluded from mainstream literary prizes. But their existence also fosters the tacit and damning assumption that genre books are looking to achieve something fundamentally different than are literary novels, and thus should be judged by a different set of criteria. And this has often held true: I’m sure not even the most avid crime-fiction fan would argue that, say, Whip Hand by Dick Francis, the Best Novel Edgar winner in 1981, was the very best novel published that year — or that it’s better than A Confederacy of Dunces, the Pulitzer winner. In fact, those two more-or-less randomly chosen books perfectly illustrate the difficulties of directly comparing such disparate literary endeavors.

And yet — what the Great Literary Convergence suggests is that this very disparateness is finally disappearing. And what a census of these awards suggest is that it was probably overstated from the start. It’s notable that no such genre-based schism exists in awards given for film; for many, The Maltese Falcon is considered a classic crime novel, while The Maltese Falcon is a considered a classic film, full stop. There was no teeth-gnashing when No Country for Old Men, a crime movie, won Best Picture — yet the novel it was (closely) based on was expressly dismissed by one prominent literary critic as “an unimportant, stripped-down thriller” that “can be read in a few idle hours.”

So what’s truly striking about looking back through the rolls of award winners is not how much difference there is, but how much agreement. There are many novels, and writers, who should have won genre and lit awards in the same year long before 2016. In some cases, the near-misses can be marked up to the whims of award juries: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale was both Booker- and Nebula-nominated in 1986, and could, and should, have won both. (Actual winners — the Booker: The Old Devils, by Kingsley Amis; the Nebula: Speaker for the Dead, by Orson Scott Card.) In other cases, the lack of overlap has less to do with the entrenched snobbery of literary juries as with the entrenched clannishness of genre ones. Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers, a Vietnam novel that’s about a drug deal gone wrong, won the National Book Award and easily could have won the Edgar — looking back, it’s clearly the most enduring crime book of 1975.

Then there are the genre authors who, while widely respected now, were unfairly prodded into their respective cattle chutes by narrow-minded critics. Ursula K. Le Guin won four Nebula awards and two Hugos, as well as a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, and her novel Orsinian Tales made the National Book Award shortlist in 1977. Yet it’s obvious that Le Guin is a writer whose work would garner much more “literary” award consideration if it were being published today. In fact, in 2014, she was awarded a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Foundation despite never having won a National Book Award for her adult fiction. (Stephen King received the same honor in 2003, despite never even having been nominated for a National Book Award.) Another such novelist: Patricia Highsmith, whose The Talented Mr. Ripley was nominated for the Edgar for Best Novel in 1956, and has enjoyed a much more robust critical afterlife than the eventual winner (Beast In View by Margaret Millar) or, for that matter, either the Pulitzer winner that year (Andersonville, by MacKinlay Kantor) or the National Book Award winner (Ten North Frederick, by John O’Hara).

On the flip side, you have novelists who established a literary pedigree early in their careers before veering into work that’s inarguably genre — such as Michael Chabon, who won the Pulitzer for The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay in 2001, then won both the Hugo and the Nebula in 2008 for The Yiddish Policeman’s Union. That novel, which takes place in an alternate-timeline Alaskan Jewish homeland, is essentially a detective story, and could just as easily have won an Edgar, too. In an alternate, more enlightened timeline, Chabon would not only be a double winner, he’d hold the coveted HEP (Hugo-Edgar-Pulitzer) trifecta.

So what The Sympathizer accomplished last week has actually been a long time coming — and is less notable for having happened now than for not having happened much sooner and much more often. But the fact that it has finally happened suggests we’ve reached a literary milestone — not least in terms of what kind of novel gets to be called “literary.” This is troubling news for the intrepid bookseller at your favorite store who’s responsible for deciding in which section to shelve Station Eleven. (At one bookstore I visited, they’d further divided novels into separate “Fiction” and “Literature” sections, and when I asked a clerk what the distinction was, he shrugged, nodded at “Literature,” and said “These people are mostly dead.”) It’s great news, however, for writers, to whom these kind of distinctions have long felt arbitrary and meaningless at best and insulting at worst. And it’s great news, of course, for readers — for whom the Great Literary Convergence happened a long time ago, at least within the more hospitable and inclusive confines of their own bookshelves.