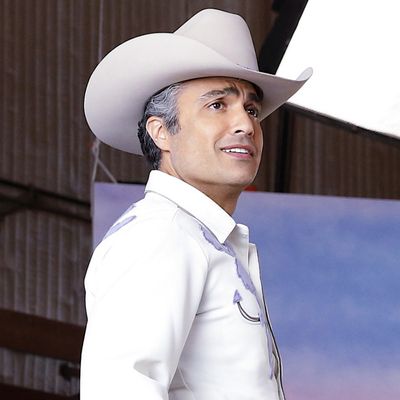

My favorite show on television right now is a sci-fi-historical-romance mashup romp, featuring a ridiculously silly lead character, almost no depth of characterization, and a dead serious political viewpoint. It’s not even a real series, not really – but Tiago: A Través Del Tiempo, Jane the Virgin’s endlessly amusing show-within-a-show, is a high point of the week in television. In it, Jane’s father, Rogelio, plays Tiago, a Doctor Who–like time-traveling meddler who arrives at various moments in history to create social change and make love. Sometimes it’s one or the other; usually it’s both at once.

Since his creation in season two, Tiago has stepped in to help Susan B. Anthony and the suffragette movement, he’s given Marie Antoinette advice on peasant relations (“just don’t say the line about cake”), and he’s supported early gay-rights movements. More recently, Tiago arrived in the midst of the Great Depression to help FDR think up the New Deal (by seducing Eleanor’s lesbian lover).

Jane the Virgin is a show so full of insistently political content, relationship arcs, melodrama, humor, and tragedy — it is a show so full — that it’s easy to overlook Tiago as fluff. I do it constantly, shoving choice Tiago quotes into the bullet-point section at the end of a recap so that I can focus on Petra’s postpartum depression or Jane’s work-life-balance tensions. After all, Tiago is essentially a simple repeating joke, built on costume sight gags and the premise that one man’s sexual generosity can alter the course of history.

But if you want to know what makes Jane work so astoundingly well, you could do worse than sitting down to take a hard look at Tiago’s Travels Through Time.

Compared to the rest of Jane’s plots, Tiago takes up a surprisingly small patch of narrative real estate. It’s one or two scenes, at most, and even those are usually just brief, snappily scripted declarations of historical passion or dramatic intent. In one episode, Rogelio wears a leiderhosen costume while dealing with other stories, and the only scrap of Tiago we get in explanation is a brief note that Tiago has to go kill Baby Hitler.

For all its brevity, though, Tiago works like a microscopic political playground. His journeys are often to great moments of progressivism in history: He’s uninterested in trench warfare or totalitarian regimes, and tends to show up at points when human rights are protected and expanded. “I’m sorry, Susan B. Anthony,” Tiago says in his first major outing. “I have to go. I’m not from this time. I was sent here to secure the women’s right to vote – and their right to love.” If the arc of history bends toward justice, Tiago is happy to be the one clutching the curve in an ardent embrace.

Jane the Virgin is not shy about its political stances. This season, we’ve gotten an immigration plot that featured the words “#Vote #Vote #Vote” printed across the screen, and much of the show is rooted in considerations of class, privilege, and representation. But Tiago takes those ideas and turns them into a full-throated, joyous historical fanfic, proudly declaring its protagonist the #FirstMaleFeminist and placing him in the midst of the Stonewall riots.

It’s not that Tiago is a simple celebration of great moments in history, or that Tiago himself is an especially aspirational figure. He’s a goofball. Plus, the premise that a roll in the hay with a mysterious Latin lover could resolve the obstacles of famous women throughout history is hardly forward thinking. But this is all part of the joke: A show about the suffragette movement, but the only way to save them is a man! Eleanor Roosevelt, but let’s just make sure her “inner beauty” is visible “on the outside,” hmm? Tiago is a marvel of doubled sincerity and irony, winking at itself while Rogelio goes swashbuckling through time, slicing and dicing through self-serious narratives of gritty realism while retaining a ramrod core of social conviction.

Part of Tiago’s formula is that, like all historical fictions, it can always be on the right side of any conflict. It’s an easy win for the show’s time-traveling lover, and for Jane. But while Tiago is off seducing suffragettes, the role of Tiago within its larger series is doing its own political work, albeit more quietly and with fewer love scenes. Although Jane the Virgin never remarks upon it or underlines it, nearly every higher-up on the production side of Tiago is a woman. Its director is always female. Rogelio has recently fallen in love with its new head writer (also a woman). A woman’s voice yells “action!” before Tiago scenes begin.

In a recent episode where Rogelio takes advantage of the Tiago set to stage a reunion between Jane and Xiomara, Jane uses two network executives to make a classically Jane joke about itself — the executives don’t want Tiago to just be about boring family problems. “Who cares about a fight between a mom and a daughter!” Ha, ha! But the better joke is that these two network executives are both women, dubiously examining this Tiago plot and feeling relieved when the episode’s writer (again, a woman) tells them that it’s actually about clones taking over the world. In this, Jane the Virgin is both reflecting its behind-the-camera demographics, and taking to heart that tired adage about being the change it wants to see in the world.

After a recent episode (the lesbian Eleanor Roosevelt story), I found myself lamenting that Tiago doesn’t have its own spinoff. More likely, I could imagine the Tiago web series, featuring five- to seven-minute clips of Tiago in the lab with Marie Curie, helping pass the Reform Act of 1832, suggesting some alternate wording for Emma Lazarus’s poem on the Statue of Liberty.

But as fun as that might be, Tiago is too embedded in the DNA of Jane the Virgin to be yanked out on its own. Rogelio’s telenovela projects have become a vital piece of the careful mechanics of Jane’s elaborate metafictional machine, and Tiago without the constant, benevolent oversight of Jane’s Beloved Narrator just wouldn’t be the same. More vitally, the subtle, alchemical impact of Tiago’s magic couldn’t exist without all of its accompanying fictional apparatuses.

Jane the Virgin is at its best when it’s weaving together layers of wry self-awareness and calls for social change with joyful, unchecked sincerity. When it falters, it’s because that’s a nearly impossible project to sustain perfectly for the length of a network season, and like an overenthusiastic interviewee, Jane’s one flaw is that it sometimes tries to do too much. Tiago, on the other hand, is the Jane the Virgin project freed from all the burdens of narrative coherence and sustained storytelling. It is buoyantly goofy and unendingly fun. Tiago’s best accomplishment is that it embodies these qualities because of, not in spite of, its deeply rooted commitment to social issues. And while it’s a fundamental element of Jane the Virgin’s identity, and I love it in that show unreservedly, I laugh the longest at Tiago, passionately dipping Susan B. Anthony into a swooning caress.