History Channel will air a remake of Roots over four consecutive nights, beginning May 30. Ahead of its premiere, Matt Zoller Seitz revisits the original series.

Roots is the most important scripted program in broadcast network history. It aired across eight consecutive nights in January 1977 — a go-for-broke gesture by ABC, which made the mini-series out of a sense of social obligation and wanted to “burn off” the entire run quickly in a mostly dead programming month. The producer was David L. Wolper, who specialized in blockbuster documentaries and mini-series (including 1982’s The Thorn Birds). The source was a book by Alex Haley, co-author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X; it was described as nonfiction until the 1990s, when African-American historians and genealogists checked Haley’s account of his family’s experiences as slaves in North Carolina and Virginia and decided that it was filled with conjecture and historical inaccuracies.

The revelations cast a pall over the program’s reputation, which is a shame. Nearly 40 years haven’t dimmed its ability to illuminate one of the grimmest aspects of U.S. history: its 200-year participation in the transatlantic slave trade and the racism that became institutionalized throughout the country up until the 1960s, barely a decade before Roots aired. When you consider Roots’ timeline proximity to the civil rights marches and riots of the sixties, the intraracial arguments about nonviolent-versus-violent resistance to oppression, and the overall whiteness of popular culture at that time, its very existence seems remarkable. Once you actually watch it, it seems still more remarkable. Haley and James Lee’s screenplay indicts white viewers in a meticulous, unrelenting way, showing that the entire nation was complicit in this horror, which ripped indigenous people from one continent and transplanted them in another, taking away language and religion and ritual and replacing it with the practices of oppressors, then insisting that they graciously accept servitude as a fact of life, or worse, as the manifestation of an alien Christian god’s will. Unknown or underappreciated black actors played slaves and former slaves. Famous, and in some cases beloved, white TV stars played plantation owners, slave traffickers, overseers, and the wives and children and hired hands who benefited from the slave-based economy even though they didn’t think of themselves as active participants in it.

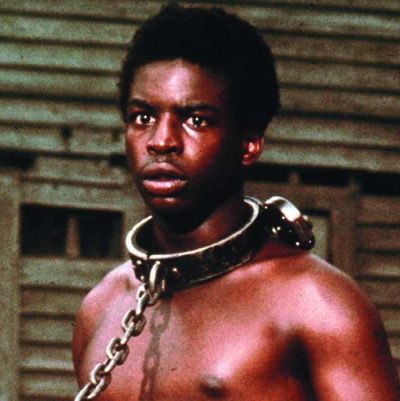

The face of the production was a young LeVar Burton, who played the Mandinka tribesman Kunta Kinte, the earliest known descendant of the author. In an iconic opening sequence that was later appropriated by Disney’s The Lion King, we see the newborn Kunta being held aloft by his father, an image of freedom and possibility that will be ground into dirt when the teenage version of the character is kidnapped by African slavers, carried across the ocean in the hold of a slave ship, and sold into bondage in Maryland, where a fellow slave named Fiddler (Louis Gossett Jr.) teaches him to speak English and advises him to accept his new “American” name, Toby, give up his Mandinka heritage, and accept his lot in life. Kunta tries to escape anyway — the first of several attempts — and is savagely whipped by an overseer. As a middle-aged slave (now played by John Amos), he tries to escape again and has part of his foot amputated with an ax as punishment. He was given a choice between that or castration. “What kind of man would do that to another man, Fiddler?” Kunta asks his friend. “Why they don’t just kill me?”

The entire production is dotted with moments of savagery this extreme, including beatings, whippings, lynchings, forced sexual relationships between female slaves and their white bosses or owners, and the separation of families whose members have been sold off to different masters. Every one of these horrific moments is justified, because the intent of Roots is to affirm the shared trauma of generations of blacks and make whites who had never really contemplated the visceral reality of it feel at least some small part of its sting. Viewers who had read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and were aware of the realities of slavery knew about the brutality, as well as the countless daily degradations, and the overall sense of despair that afflicted people who had been reduced to the status of glorified livestock to be worked, bred, sold, and put down. As in a silent melodrama (a mode that might have inspired parts of Roots), every scene is conceived in very broad strokes, and there’s no ambiguity about what’s happening or what it means for the characters; but the bedrock of Roots is still a historical vision of considerable sophistication. It’s showing us an inverted form of colonialism: Rather than going to another country to superimpose their culture, the mini-series’ European-descended whites have brought Africans to North America, then systematically beaten and bred their indigenous culture out of them over the course of several generations. The casually doled-out whippings, the almost lordly indifference of the plantation owners, the repeated insistence that the slaves speak English and worship the Christian God, all testify to the mass brainwashing that was necessary to maintain the slave economy. As early as episode two, the sound of fiddle-dependent European folk music, which replaced the Mandinka drums of the opening section, starts to seem psychically oppressive: aural shackles.

Roots brought it all into American living rooms, night after night, and dramatized it through well-written characters portrayed by actors with imagination and empathy. For many white viewers, the mini-series amounted to the first prolonged instance of not merely being asked to identify with cultural experiences that were alien to them, but to actually feel them — by watching Kunta and his fellow slaves struggle to be free, either physically or emotionally, only to realize that in a country that had institutionalized white supremacy and had no compelling reason to change its ways, it just wasn’t possible.

The bulk of Roots’ messages and meanings were transmitted through its black actors: Burton; Gossett; Amos; Cicely Tyson (as Kunta’s mother, Binta); Madge Sinclair (as Belle Reynolds, who falls in love with the middle-aged, maimed Kunta); Leslie Uggams (as Kizzy Reynolds, Kunta and Belle’s daughter, who was secretly taught to read and write); Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs (as Kizzy’s lover Noah, who tries to escape as Kunta did before him); and Ben Vereen (as the future cockfighting impresario “Chicken” George Moore, Kizzy’s son by a white slaveholder). Many of the performances are as saddening as they are revelatory: Hilton-Jacobs, who was stuck playing a smooth-talking clown on Welcome Back, Kotter, is heroically righteous as Noah, and Amos and Sinclair’s tenderness in love scenes reminds us of how rarely African-American performers were allowed to play romantic, sexual beings on national TV in the ’70s. (When Kunta and Belle meet secretly in a barn, she strokes his shoulders and cradles his face, then removes his shirt and caresses the whip scars on his back, and he speaks to her in their native language, home at last.)

But the show’s casting masterstroke occurred in the white roles. They were filled by actors who had usually played sympathetic, adorable, or noble characters. Ed Asner, best known as the curmudgeonly but honorable Lou Grant on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, played the hired captain of the ship that brought Kunta and other kidnapped Africans to the United States. The moment when he’s shown the blueprint of the ship and realizes what those cramped berths and shackles are for, then accepts the job anyway, might be the most damning statement TV had yet made about the white man’s ability to compartmentalize revulsion when there was money to be made. The overseer on the voyage who assures the captain that the slaves aren’t really human is played by Ralph Waite, the crinkly-eyed dad from The Waltons. Chuck Connors, the righteous widowed rancher from The Rifleman, plays Tom Moore, a planter who rapes and impregnates Kizzy. Dr. William Reynolds, portrayed by Robert Reed, the father from The Brady Bunch, at first seems like a fairly benign master, at least compared to some of the openly sadistic characters we’d met up until that point; he assures his slaves that he won’t splinter blood ties by selling any of them off. But when Noah tries to escape, he changes his mind and sells Noah and Kizzy to separate plantations. Kizzy turns to Missy Anne Reynolds (played by Broadway’s Peter Pan, Sandy Duncan) for help because they’ve always been close; but when Kizzy’s carted off, screaming, “No, no, I don’t want to go!” Missy Anne watches through an upstairs window, her face a cold mask. The political and emotional reality of Roots’ drama is still stunning. Nothing happens that would not have happened. There is no hand-holding of white viewers, no dog-whistle assurances that if they were in this situation, they would not have behaved abominably. Time and again, the white characters are faced with a stark choice: Do the morally right thing and set themselves in opposition to slave culture, or maintain the status quo and hold on to their privileges. They always go with the second option.

Roots was produced on the cheap, with blandly lit interior scenes, unconvincing old-age makeup, and scrub-dotted California locations standing in for the humid greenness of the former Confederate States, and the physical continuity in the casting is sometimes laughable (in no universe does LeVar Burton grow up to become John Amos). But for all its missteps and faults, and there are many, it is distinguished by its moral and political clarity about what slavery was and what it meant to U.S. history and African and African-American identity. A sequel, Roots: The Next Generations, followed in 1979, and was nearly as good, following the family’s story through Reconstruction, the Northern migration, Prohibition, World War II, and the 1960s. It featured Marlon Brando in a cameo as Ku Klux Klan leader George Lincoln Rockwell, and culminated with Alex Haley (James Earl Jones) meeting his first great subject, Malcolm X (Al Freeman Jr.), then returning to his family’s ancestral village in Jufureh, the Gambia, Africa. The saga ends with a griot telling Haley the story of a young man named Kunta Kinte. The power of this moment, like so many others in Roots, is overwhelming, and it renders the questions of historical accuracy largely moot. This is not the story of one man’s family, but the story of a nation’s secret history, a tale that hasn’t yet been fully engaged with and understood, and that still lacks a satisfying ending.