It was bound to happen, and now it has. The rollicking 17-artist group show of gallery painters at Canada Gallery is called ÔÇ£Make Painting Great Again.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a terrible title, I know,ÔÇØ groaned garrulous Phil Grauer, one of the galleryÔÇÖs four artist-owners. In fact, the show is a blast of fresh air.

Canada is known for showing a lot of painters. Seventeen in one gallery is a lot. Usually too many. Often when a gallery appears to specialize in painting the medium starts to feel like an endangered species, protected by keepers of the flame and those who think painting needs to go back to the good old days, whenever those days might have been. (The Caves?) Then there are the curators and academics who turn painting into an IRL issue of Artforum┬áÔÇö a kind of textbook illustration, meant to be narrow, ideological, theoretically correct, black-and-white or mostly monochrome with elements of the photographic, somehow official, good for us. These people treat painting like a policy paper and a private club.

None of this is going on at Canada. Not by a long shot. Not only do you never feel you are looking at things through the filters of money and professionalism, the show is a wide-ranging pr├®cis on some of the ways that painting is expanding by exploring tradition. Like it is at lots of galleries these days ÔÇö two of them (Jack Hanley and Nicelle Beauchene) just steps away on Broome Street┬áÔÇö at Canada painting is a wild card taking many forms, all of them optically complex and rigorous. This show is especially exciting. Just inside the door is one of the hottest painters around, Katherine Bernhardt. I donÔÇÖt mean sheÔÇÖs hot in the market way ÔÇö although sheÔÇÖs getting that way too. Bernhardt is hot the way painters use the word to mean wild-style chops and tons of visual energy. I canÔÇÖt think of another painter whose paintings are more fun to look at ÔÇö pleasure principles, illustrated. Her spray-painted and brushed paintings of plantains, palm branches, cigarettes, and cell phones are as big as minivans, loud, neon-colored channelings of Matisse and Helen Frankenthaler by way of the Simpsons and fast-food paper place mats.

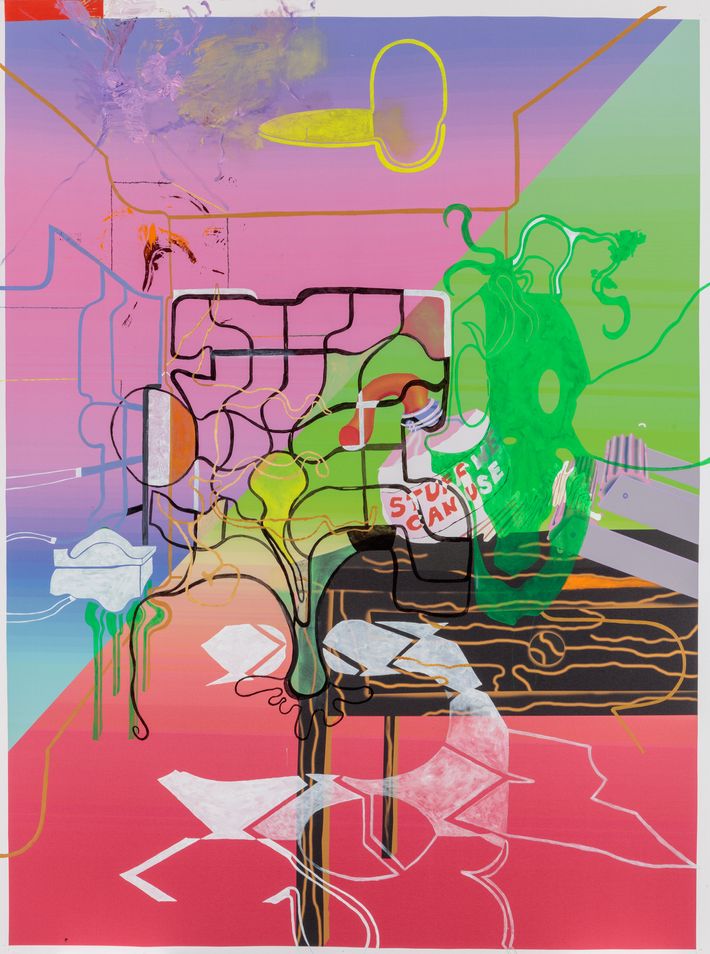

Next to Bernhardt is Michael WilliamsÔÇÖs big new Bet It All on Number Twive, a happily horrid florid burst of chartreuse and lilac sporting a receding table and a Peter SaulÔÇôlike oozing pain tube labeled Stuff We Can Use. As apt a description of the gallery aesthetic as any. You canÔÇÖt make out image for abstraction, and the surface goes from feeling deep to digitally thin, trailing off at the edges and turning geometric as Pop references vie with non-objective-painting compositional techniques. Williams is now not only one of the better painters around; heÔÇÖs also one of the hottest, marketwise.

Which is kind of why IÔÇÖm writing about this summer gallery group show, which I take to represent something of a tipping point for the scene writ large. Canada is now one of the best galleries to have opened since the turn of the millennium. It has ÔÇ£discoveredÔÇØ and nurtured a number of now well-known painters: in addition to Williams, Joe Bradley, and Matt Connors, for instance; Bernhardt started elsewhere, but came to light at Canada. I donÔÇÖt know what the ins and outs of the business arrangements are, but not only have BradleyÔÇÖs resale prices soared over a million dollars, he just had a show at Gagosian (after showing with Gavin Brown, as well). Williams, meanwhile, now exhibits with powerhouse Zurich gallery Eva Presenhuber, which is rumored to be opening big in New York soon. I hear he also shows with Gladstone Gallery. Bernhardt just showed with Venus Over ManhattanÔÇÖs two galleries (Venus does not represent artists). All this is natural. Artists grow and branch out. The question becomes: Are they just ÔÇ£branching out,ÔÇØ or are they really leaving? And where does that leave Canada?

IÔÇÖve thought of this as IÔÇÖve seen the work of all these artists in major art fairs in the booths of major galleries. Not Canada. ThatÔÇÖs because the gallery hasnÔÇÖt been allowed in any of the all-important Art Basel art fairs, in Basel, Miami, or Hong Kong. Canada isnÔÇÖt the only one; except for a handful of super-hip galleries that are automatically invited to everything, numbers of galleries at CanadaÔÇÖs stage of development do not get to participate in those fairs. This is a problem, because we live in a time when 50 percent or more of a galleryÔÇÖs annual income might come from fairs. Which means that one of the biggest sources of profit and connection-making for growing galleries like Canada ÔÇö selling high-end work at high-end art fairs ÔÇö is completely cut off. Moreover, work made by these artists but shown by other megagalleries in fairs is work that might otherwise have been shown and sold from the gallery. ThatÔÇÖs not only a big financial blow for a medium-sized or small gallery to absorb, it means that scores of new clients are being appropriated by these other bigger galleries. Which means that these artists are slowly going to be better served by these bigger galleries. Thus it advantages big galleries at Art Basel and other fairs that Lower East Side gallerists like Canada donÔÇÖt get a seat at that table. This pattern is playing itself in many galleries at this stage of growth.

Looking at the Canada show made me think of what I call the Gavin Brown paradigm. Brown, an artist, opened on a shoestring in a teeny storefront on West Broome Street, in 1994. He showed artists like Peter Doig, Chris Ofili, Elizabeth Peyton, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and many others who have gone on to worldwide fame. He then moved to a bigger, still funky space on West 15th Street, expanded there, then opened a bar called Passerby before moving to Leroy Street and then expanding there again. That building was sold and knocked down by developers. Now heÔÇÖs opened in a huge space in Harlem. Like Canada and other Lower East Side galleries, Brown has always shown important new art but it has always projected an ambience of family ÔÇö making it up as he went, exuding old-school commitment to some greater cause. Now Brown is one of the best galleries in the world.

One of the many keys to BrownÔÇÖs survival was that many of his artists stuck with him as the gallery grew at a slower rate than their careers. Eventually his biggest artists left him; Ofili shows with Zwirner, Peyton with Gladstone, and Doig with Michael Werner. Yet in those first crucial years they didnÔÇÖt break away to those bigger, richer, more high-profile galleries and the gallery got stronger. Brown was able to sustain these losses when they came, even if he had rocky years with patchy shows, looking occasionally like he wouldnÔÇÖt recover. Indeed, all galleries must be able to withstand losing their original big artists almost as a rite of passage; it proves a galleryÔÇÖs vision is bigger than one or two artists and runs deep in the gallerist. (Many galleries are not financially, psychologically, or spiritually able to go through this terrible, painful phase; many gallerists turn bitter, blame ÔÇ£the market,ÔÇØ and close.) This knotty ecology of growth is still just as fragile and fraught; but conditions have gotten harsher. First, because everything is so spread out and there are so many more artists and spaces, galleries take much longer to get traction. And the costs of opening and staying open are far higher, as well. This means longer hard times at the same moment artists need bigger galleries. As a result, when artists jump galleries itÔÇÖs a bigger shock to the system. This is exactly where a number of growing Lower East Side galleries find themselves. As the numbers and money have changed, big galleries and big money are coming in earlier, and harder, than ever, and offering more.

I donÔÇÖt know what the situation at Canada is. IÔÇÖm too nervous to ask. After opening in 1999 in a funky basement on Broadway in Soho and then moving to an equally funky place on Lower Christie the gallery moved again to its current roomy space on Broome, and even recently took the space next door. Across the board smaller galleries have repeated this pattern, expanding to accommodate their artists. I donÔÇÖt know how the cycle will play out. By way of hope and tough love, in the most brutal Darwinian terms I can put this, over the decades IÔÇÖve found that the best of young galleries survive this hard part of the cycle and then go on to greatness.