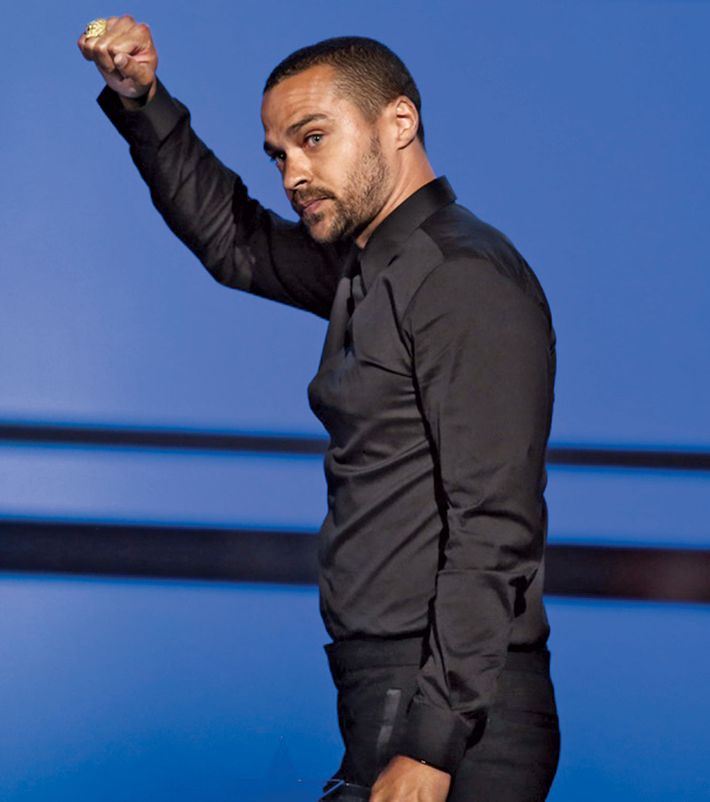

American music has always been a great and complex exchange. But who, exactly, gets to borrow from whom, and under what conditions, has become increasingly controversial. Paul Simon’s Graceland album — about to celebrate its 30th anniversary — was criticized at the time of its release for Simon’s use of “African” musical elements. Now? It’s almost impossible to imagine a white musician even attempting a similar experiment. The cultural stakes are too fraught, a point underscored by Grey’s Anatomy actor and activist Jesse Williams during a speech at the BET Awards in June in which he criticized white “gentrification” of black culture. What sounds to one listener like homage can sound to another like theft or, more politely, appropriation. And with the white-rapper likes of Macklemore and Iggy Azalea earning Best Rap Album Grammy nominations (as well as millions of dollars) — that can be hard to swallow for those who see hip-hop as a black form.

The appropriation issue, recently renewed and given a new energy by the passionate rhetoric of Black Lives Matter, has been around since at least the early 20th century. But are we just talking in circles? Is there a way forward? Here, New York pop-music critic Craig Jenkins and Vulture music columnist Frank Guan wrestle with the subject.

What is gained and what is lost by an increased sensitivity to cultural appropriation? What does acceptable cultural borrowing look like? Is it possible? Or even particularly desirable?

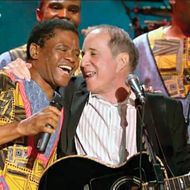

Craig Jenkins: I’m glad to have Graceland In 2014, Steven Van Zandt, the E Street Band member, accused Simon of having distracted from the anti-apartheid movement with Graceland and also of downplaying his cultural borrowing. “He actually had the nerve to say, ‘Well, I paid everybody double scale,’ ” said Van Zandt of Simon.to point to, because for me it’s an example of cultural exchange that — for all the complaints about the exploitative implications of a then-floundering white American folk musician sneaking off to South Africa and coming back with mountains of cash and the Grammy for Album of the Year — effected a net good. Sure, Simon broke boycotts intended to pressure the apartheid ruling power, but Graceland also put a human face on the struggle and introduced millions of Americans to the rich music of Africa. He helped make Ladysmith Black Mambazo

In 2014, Steven Van Zandt, the E Street Band member, accused Simon of having distracted from the anti-apartheid movement with Graceland and also of downplaying his cultural borrowing. “He actually had the nerve to say, ‘Well, I paid everybody double scale,’ ” said Van Zandt of Simon.to point to, because for me it’s an example of cultural exchange that — for all the complaints about the exploitative implications of a then-floundering white American folk musician sneaking off to South Africa and coming back with mountains of cash and the Grammy for Album of the Year — effected a net good. Sure, Simon broke boycotts intended to pressure the apartheid ruling power, but Graceland also put a human face on the struggle and introduced millions of Americans to the rich music of Africa. He helped make Ladysmith Black Mambazo A South African group performing the choral traditions of isicathamiya and mbube, Ladysmith came to international prominence for its backing vocals on Graceland. international stars in the process.

A South African group performing the choral traditions of isicathamiya and mbube, Ladysmith came to international prominence for its backing vocals on Graceland. international stars in the process.

If you’re an artist dabbling in a culture you weren’t born into, you should make yourself a conduit of the people’s art and journey. Simon’s Graceland move is leagues more mindful than the similarly culturally voracious move of someone like Iggy Azalea, Azalea, a white Australian, faced heavy criticism for using a southern black idiolect on her summer-defining 2014 single “Fancy.” Rapper Jean Grae compared the act to “verbal blackface.” for instance, who it’s clear is reveling in the language and mannerisms of hip-hop without expressing much concern for the history of the culture, the plight of the people in the cities that fuel it, or her own curious place in it. When she walks off with a string of chart-toppers — while remaining unapologetic in the face of conversations about how her path has been made easier by being an attractive white woman in the entertainment business — it feels like she’s made off with them at black art’s expense.

Azalea, a white Australian, faced heavy criticism for using a southern black idiolect on her summer-defining 2014 single “Fancy.” Rapper Jean Grae compared the act to “verbal blackface.” for instance, who it’s clear is reveling in the language and mannerisms of hip-hop without expressing much concern for the history of the culture, the plight of the people in the cities that fuel it, or her own curious place in it. When she walks off with a string of chart-toppers — while remaining unapologetic in the face of conversations about how her path has been made easier by being an attractive white woman in the entertainment business — it feels like she’s made off with them at black art’s expense.

In response to Williams’s speech, “We’re done,” said Williams in his acceptance speech for the BET Humanitarian Award, “watching … while this invention called whiteness uses and abuses us … extracting our culture … our entertainment like oil — black gold — ghettoizing and demeaning our creations, gentrifying our genius.” Justin Timberlake made a gaffe on Twitter

“We’re done,” said Williams in his acceptance speech for the BET Humanitarian Award, “watching … while this invention called whiteness uses and abuses us … extracting our culture … our entertainment like oil — black gold — ghettoizing and demeaning our creations, gentrifying our genius.” Justin Timberlake made a gaffe on Twitter During the BET Awards, Timberlake tweeted that he felt “#inspired” by Jesse Williams’s speech. Philadelphia writer Ernest Owens responded, “So does this mean you’re going to stop appropriating our music and culture?” Timberlake replied that he felt “misunderstood.” for which he was roasted online and for which he was compelled to apologize. This attests to a third kind of cultural borrowing in pop music that’s quickly coming under fire as politically savvy people are finding a voice on Twitter. Timberlake is a white artist who gives all appearances of being “down” with black culture, who benefits from a light coat of black inner-city flavor, but, as a former child star, reverts to media-coached, America’s-sweetheart mode when controversy arises. I think about Justin Bieber

During the BET Awards, Timberlake tweeted that he felt “#inspired” by Jesse Williams’s speech. Philadelphia writer Ernest Owens responded, “So does this mean you’re going to stop appropriating our music and culture?” Timberlake replied that he felt “misunderstood.” for which he was roasted online and for which he was compelled to apologize. This attests to a third kind of cultural borrowing in pop music that’s quickly coming under fire as politically savvy people are finding a voice on Twitter. Timberlake is a white artist who gives all appearances of being “down” with black culture, who benefits from a light coat of black inner-city flavor, but, as a former child star, reverts to media-coached, America’s-sweetheart mode when controversy arises. I think about Justin Bieber In 2014, after a string of DUI, vandalism, and assault charges, Bieber sought public atonement by spending time with pastor to the stars Carl Lentz. turning very publicly to Jesus when his hip-hop-inflected bad-boy persona started drawing court cases. I wonder how we would’ve weathered Gwen Stefani’s and Fergie’s squeaky-clean early-aughts hip-hop incarnations in this climate. Or Madonna’s “La Isla Bonita” video.

In 2014, after a string of DUI, vandalism, and assault charges, Bieber sought public atonement by spending time with pastor to the stars Carl Lentz. turning very publicly to Jesus when his hip-hop-inflected bad-boy persona started drawing court cases. I wonder how we would’ve weathered Gwen Stefani’s and Fergie’s squeaky-clean early-aughts hip-hop incarnations in this climate. Or Madonna’s “La Isla Bonita” video. In the video for the 1986 single “La Isla Bonita,” Madonna appears surrounded by black and Hispanic performers. She’s the only white person in the video, which seems to exoticize people of color. I think I know acceptable cultural exchange when I see it, and it looks like collaboration, not costume, like advocacy, not avoidance. But I wonder if these nuances matter anymore.

In the video for the 1986 single “La Isla Bonita,” Madonna appears surrounded by black and Hispanic performers. She’s the only white person in the video, which seems to exoticize people of color. I think I know acceptable cultural exchange when I see it, and it looks like collaboration, not costume, like advocacy, not avoidance. But I wonder if these nuances matter anymore.

Frank Guan: It seems to me that the question of what constitutes “permissible” borrowing of black-American music is something that black Americans decide among themselves through a continuous process of informal dialogue. If their music is rooted in their social position and represents a mode of political resistance, then it’s not just chords or rhythms or postures that are at stake for black Americans when their culture is (sometimes beautifully, but most times ineptly) replicated by the white majority for its own benefit: Their spiritual identities are on the line in a way that white Americans’ would not be if a black musician adopted, say, a Burt Bacharach tune for his or her own purposes. On his 1969 album Hot Buttered Soul, Isaac Hayes transformed Bacharach’s “Walk On By” into a spellbinding exercise in funk. To my mind, great art fails to embody a better world, but it carries the promise of such a world and encourages its audience to be worthy of it. Mediocre art, on the other hand, reiterates the world as it already is: Lacking transformative energy, it can only reflect the stinginess and squeamishness of its society of origin.

On his 1969 album Hot Buttered Soul, Isaac Hayes transformed Bacharach’s “Walk On By” into a spellbinding exercise in funk. To my mind, great art fails to embody a better world, but it carries the promise of such a world and encourages its audience to be worthy of it. Mediocre art, on the other hand, reiterates the world as it already is: Lacking transformative energy, it can only reflect the stinginess and squeamishness of its society of origin.

In the end, I suspect that the more profoundly one is influenced by an artist from a different culture, the more one recognizes the foreign artist as someone intelligent enough to understand the consequences of choices of technique and feeling, and as someone mature enough to accept those consequences. It’s hard to do all that without accepting the other artist as, at the very least, a fellow human being. And it’s very hard to imagine anyone who could seriously resent the existence of albums like Graceland or the Talking Heads’ Afro-beat-indebted Remain in Light (or of individual songs like Bowie’s James Brown–influenced “Fame” or Kurt Cobain’s version of “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” a traditional Appalachian song made famous by Lead Belly) simply because the artists are white while their musical influences are black. Quality matters in itself, but in these cases the excellence of the music testifies to the depth of the artists’ engagement with, and acceptance of, black humanity. Likewise, regarding the more recent artists that Craig cites, it’s difficult not to suspect that the lack of quality reflects a carelessness and obliviousness regarding black people so typical in society that its aesthetic reiteration, however profitable, is ultimately pointless.

Perhaps a more interesting question has to do with why, in the 30 years between now and Graceland, the number of instances where white musicians combine the genius of black musical culture with their own seems to have diminished. Is it just the ascendance of hip-hop, or is there something more at work?

Jenkins: I don’t think musicians are ever going to stop dabbling and borrowing, especially where there’s money to be made. Look at all the country guys talk-singing over programmed drums in the last three years. What is going to happen — is happening already — is that artists who employ aspects of, let’s say, hip-hop, without having to don the social and political stigmas that come with blackness, are going to have to do more reading about and listening to and speaking out for the culture that inspires them. The relationship needs to be reciprocal, and for many stars who’ve gotten very rich through some measure of cultural siphoning, it isn’t. And people are tired of that. And they have a means of carrying their displeasure directly to the offending parties and drumming up bad press without much effort. You used to have to mail off a letter when you were mad at a musician. Now a simple tweet will suffice.

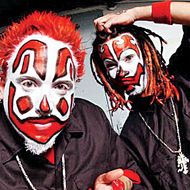

There are nuances to being an ally, too. Many rap fans found Macklemore’s advocacy for black and gay rights a touch disingenuous, particularly after he made a big show of regretting having won Grammys he thought would go to Kendrick Lamar. After winning Best Rap Album at the 2014 Grammys, Macklemore posted an Instagram message intended for fellow nominee Kendrick Lamar: “You got robbed. I wanted you to win. It’s weird and sucks that I robbed you.” He came off as too considerate to be believed, and that was just as upsetting for people as “Thrift Shop” burning up charts and racking up Grammys. For all his faults, Eminem in the first few years of his fame (before he became crabby and exasperating) is an example of a white rapper who approached the intersection of his race and fame smartly. He tapped Dr. Dre as his mentor, lent his stardom to lesser-known artists through his Shady Records label, and worked doggedly at his craft. If all of this seems like coincidence, consider his care in choosing sparring partners: Insane Clown Posse, Everlast, Fred Durst, Moby, *NSYNC — see a pattern?

After winning Best Rap Album at the 2014 Grammys, Macklemore posted an Instagram message intended for fellow nominee Kendrick Lamar: “You got robbed. I wanted you to win. It’s weird and sucks that I robbed you.” He came off as too considerate to be believed, and that was just as upsetting for people as “Thrift Shop” burning up charts and racking up Grammys. For all his faults, Eminem in the first few years of his fame (before he became crabby and exasperating) is an example of a white rapper who approached the intersection of his race and fame smartly. He tapped Dr. Dre as his mentor, lent his stardom to lesser-known artists through his Shady Records label, and worked doggedly at his craft. If all of this seems like coincidence, consider his care in choosing sparring partners: Insane Clown Posse, Everlast, Fred Durst, Moby, *NSYNC — see a pattern? White, white, white, white, and blindingly white.

White, white, white, white, and blindingly white.

It’s like a cookout. Come, laugh, and eat till you’re stuffed. And, especially if you’re thoughtful enough to bring something to the table and to show some respect, you’ll be fine.

Guan: Agreed: It’s not what you take so much as what you give back. It might be possible to interpret Jesse Williams’s speech, and other statements along those lines, as the assertion of some kind of total embargo on the importation of black culture by nonblack people, but I don’t think that’s really the issue. The issue concerns a very specific set of artists, occupying a superior social position to the artists and culture whose posturing and sounds they mimic, who leverage their status to garner fame and fortune — a fame and fortune they then deploy to obscure their lack of cultural intelligence and/or aesthetic value.

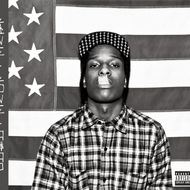

To take your cookout analogy and run with it, Craig, there’s a difference between, on the one hand, borrowing (hopefully with the appropriate level of tact and gratitude) someone else’s wine to add flavor to a dish of your own creation and, on the other hand, simply watering down that wine and then selling it to your well-off friends at a markup. I can’t be mad at the RZA and the rest of the Wu-Tang Clan Since their 1993 debut, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), the Staten Island hip-hop collective has drawn deeply from martial-arts mythology and iconography. for re-creating Asian martial-arts films in their own image, because they’re clearly doing something new and excellent; moreover, as far as I can tell, they’ve always been forthright about what they owe to Chinese culture. Or take the instrumental to A$AP Rocky’s “Peso,”

Since their 1993 debut, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), the Staten Island hip-hop collective has drawn deeply from martial-arts mythology and iconography. for re-creating Asian martial-arts films in their own image, because they’re clearly doing something new and excellent; moreover, as far as I can tell, they’ve always been forthright about what they owe to Chinese culture. Or take the instrumental to A$AP Rocky’s “Peso,” The fashion-forward Harlem rapper shot into the Zeitgeist with his 2011 mixtape, Live. Love. ASAP. which sounds like alternate background music for Chun-Li’s stage in the Street Fighter video game. It sounds heavenly, and that’s enough; it doesn’t matter that “Peso” helped pave the way for Rocky to be rich and famous. Who knows, it might not even matter that the four Englishmen in Led Zeppelin

The fashion-forward Harlem rapper shot into the Zeitgeist with his 2011 mixtape, Live. Love. ASAP. which sounds like alternate background music for Chun-Li’s stage in the Street Fighter video game. It sounds heavenly, and that’s enough; it doesn’t matter that “Peso” helped pave the way for Rocky to be rich and famous. Who knows, it might not even matter that the four Englishmen in Led Zeppelin The rock icons have been accused of giving insufficient credit to the black blues musicians whose work the band often drew from. achieved enormous wealth and celebrity in part by copying the blues (and Celtic music, and Indian music, and funk, and reggae) so long as their music is superb. It’s arguable, at the very least, and there’s no way to win that argument decisively. But a demonstrably mediocre pilferer of other people’s music who, by capitalizing on easy access to a larger, wealthier, less-discerning core audience, converts their social superiority into bogus cultural achievement? In such a case I think we can firmly conclude that, speaking morally or aesthetically, we could stand to hear a lot less.

The rock icons have been accused of giving insufficient credit to the black blues musicians whose work the band often drew from. achieved enormous wealth and celebrity in part by copying the blues (and Celtic music, and Indian music, and funk, and reggae) so long as their music is superb. It’s arguable, at the very least, and there’s no way to win that argument decisively. But a demonstrably mediocre pilferer of other people’s music who, by capitalizing on easy access to a larger, wealthier, less-discerning core audience, converts their social superiority into bogus cultural achievement? In such a case I think we can firmly conclude that, speaking morally or aesthetically, we could stand to hear a lot less.

The question of who gets to speak about what (and how) only seems to get harder to answer and more tortured. The recent online arguments over who should be allowed to pass judgment on Beyoncé’s most recent album and who shouldn’t aren’t quite the same thing as the appropriation debate, but they’re touching on similar issues. How has the conversation about appropriation affected the way we talk about, and understand, artists?

Jenkins: Appropriation, underrepresentation, and disenfranchisement are all different parts of the same beast, and when people tire of fighting against the one, the patience to weather the others evaporates. The hand-wringing about who should write about the Beyoncé album, To pick one example, journalist Damon Young wrote a piece in which his advice to white writers covering Beyoncé’s Lemonade included “don’t” and “wait.” for instance — I caught flak for writing about it here, myself — was about black women in media feeling like there isn’t enough space for them in arts journalism. When you juxtapose these writers’ sentiments with black artists’ feeling constrained in their success by their race, it, to me, looks to be a different version of the same thing.

To pick one example, journalist Damon Young wrote a piece in which his advice to white writers covering Beyoncé’s Lemonade included “don’t” and “wait.” for instance — I caught flak for writing about it here, myself — was about black women in media feeling like there isn’t enough space for them in arts journalism. When you juxtapose these writers’ sentiments with black artists’ feeling constrained in their success by their race, it, to me, looks to be a different version of the same thing.

Another recent, poignant example: Kanye West taking umbrage at the reviews of The Life of Pablo Kanye West’s seventh album is a sprawling, seemingly continually in-process meditation on race and fame. in February. The album got rave reviews, but after earning a rare 9.0 (out of 10) from Pitchfork, West went off on Twitter, saying, “Pitchfork, the album is a 30 out of 10,” which a lot of people understandably took for another bit of textbook Kanye haughtiness. But his follow-up tweet was more pointed: “To Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, New York Times, and any other white publication. Please do not comment on black music anymore … I love love love white people but you don’t understand what it means to be the great grandson of ex slaves and make it this far.” The response from the majority of music blogs, which mystified me, was to run the remarks as another Kanye outburst and move along. This was a missed opportunity to unpack what it means for a prominent black artist to view outlets that cover his music as “white publications” covering a culture they weren’t born into. What he’s saying, albeit crassly, is that there are aspects of blackness that are not universally understood, and that this should be taken into consideration, however loosely, in the coverage of music. This isn’t a new sentiment: Prince used to send music publications scrambling because he would specifically request black journalists to do his interviews. (Never the easiest subject to cover, Prince also used to forbid journalists, of any race, to record the interviews they’d done with him.)

Kanye West’s seventh album is a sprawling, seemingly continually in-process meditation on race and fame. in February. The album got rave reviews, but after earning a rare 9.0 (out of 10) from Pitchfork, West went off on Twitter, saying, “Pitchfork, the album is a 30 out of 10,” which a lot of people understandably took for another bit of textbook Kanye haughtiness. But his follow-up tweet was more pointed: “To Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, New York Times, and any other white publication. Please do not comment on black music anymore … I love love love white people but you don’t understand what it means to be the great grandson of ex slaves and make it this far.” The response from the majority of music blogs, which mystified me, was to run the remarks as another Kanye outburst and move along. This was a missed opportunity to unpack what it means for a prominent black artist to view outlets that cover his music as “white publications” covering a culture they weren’t born into. What he’s saying, albeit crassly, is that there are aspects of blackness that are not universally understood, and that this should be taken into consideration, however loosely, in the coverage of music. This isn’t a new sentiment: Prince used to send music publications scrambling because he would specifically request black journalists to do his interviews. (Never the easiest subject to cover, Prince also used to forbid journalists, of any race, to record the interviews they’d done with him.)

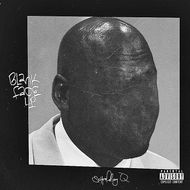

Now, cordoning off the coverage of music and the creation of music by race might solve one problem, but it creates others. It’s a bad idea, ultimately, because it doesn’t allow for the freest exchange of ideas. (I say this as a black Harlemite who, in the space of four days, followed up going to a Garth BrooksThe country-music superstar is the all-time best-selling solo artist in America. show with a Schoolboy Q A member of the Black Hippy collective along with Kendrick Lamar, Schoolboy Q released his fourth album, the savvy and psychedelic Blank Face LP, in July. concert.) We have to be respectful of and curious about our differences, and constantly and vigilantly look for ways to promote inclusiveness, and one day — maybe — the nagging feeling that the arts (and the thinking and writing about those arts: that is, their criticism) could stand to look a little more representative of the society they come from will start to fade away.

A member of the Black Hippy collective along with Kendrick Lamar, Schoolboy Q released his fourth album, the savvy and psychedelic Blank Face LP, in July. concert.) We have to be respectful of and curious about our differences, and constantly and vigilantly look for ways to promote inclusiveness, and one day — maybe — the nagging feeling that the arts (and the thinking and writing about those arts: that is, their criticism) could stand to look a little more representative of the society they come from will start to fade away.

Guan: A critic who shares a social background with the artist they’re reviewing has an innate advantage over a critic who doesn’t. Criticism is a blend of formal analysis and empathy, and a social group defines itself in part by a higher capacity for empathy for those within it than without.

With that being said, cultural advantages aren’t necessarily decisive. Receptiveness to art is as much a personal matter, something to be tested and improved in solitude, as it is a matter of group solidarity. And, as much as I wish it weren’t the case, bad writing and slipshod thinking are the only things that are irrefutably capable of transcending all social and cultural boundaries.

In the end, the challenge for writers — and listeners — is the same: to be maximally receptive and convincing when presenting one’s perspective. When it comes to writing about black musicians, the obstacles are different for the white writer who’s socially empowered but culturally peripheral and for the black writer who’s socially peripheral but culturally at home. The former needs to develop literacy in black culture; the latter has to find a way to express specific cultural knowledge while also remaining accessible. Neither is an easy task.

Of course, it’s hard for any people who are socially dispossessed not to feel extra possessive when it comes to their cultural icons and their reception by a more socially dominant audience, particularly when there’s ample evidence of those same icons being celebrated (and dismissed) by the majority in an ignorant way. It’s kind of bleak right now: You have a tug-of-war between black cultural preeminence and white social dominance, and it’s hard to see how either side can give way.

*This article appears in the July 25, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.