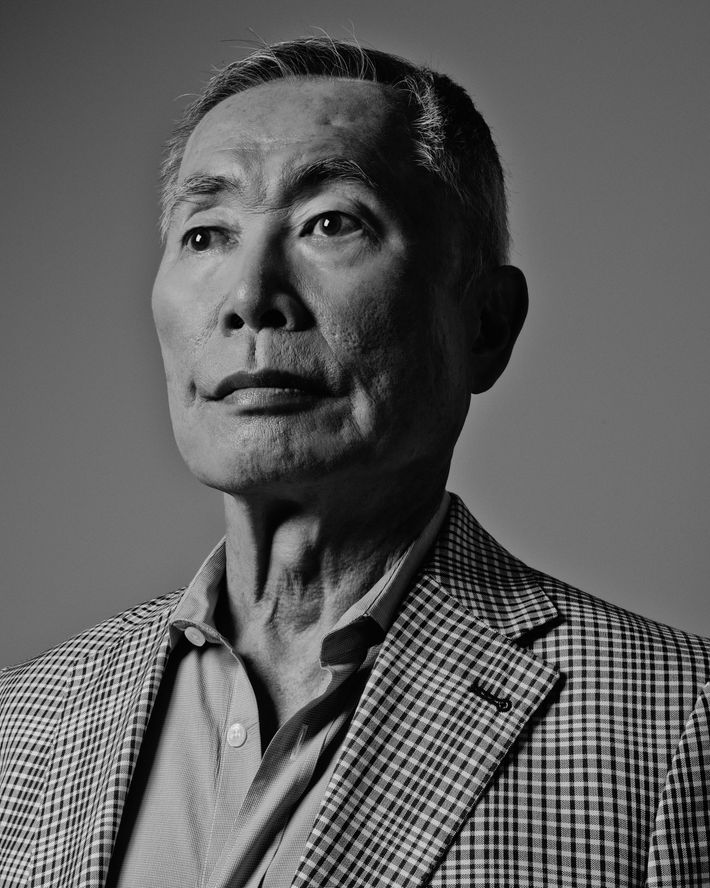

I hear George Takei’s voice greeting me before I see him: His warm baritone fills the hallway when I get off the elevator on his floor. Takei is standing in the doorway, wearing a neat blazer and Onitsuka Tiger sneakers, and ushers me into the compact one-bedroom apartment he stays in when he’s working in New York. (He considers Los Angeles home, where he lives with his husband, Brad Takei.) At 79, Takei is still as busy as ever. He has lined up another theater gig, this time as the Reciter in Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s musical Pacific Overtures, opening next spring, and most recently made headlines in advance of the upcoming Star Trek film, which will reveal that Sulu, the character originated by him and played by John Cho in the reboot, is gay, as an homage to Takei. In a twist, he said that he would rather have seen the filmmakers create a new character, rather than make Sulu gay.

Takei and I spoke twice, once in his apartment after Pride weekend, and again in advance of the Star Trek release. We talked about his past, frequenting gay bars as a closeted actor, the history of yellowface in Hollywood, and yes, his thoughts on making Sulu gay.

How was your Pride weekend?

It was nice and lively. I spoke at a big, 800-seat theater around Ryerson College, smack dab in the heart of downtown Toronto, exactly to the day a year from the Supreme Court ruling. So I noted that, and the horrific event in Orlando.

The shooting in Orlando bound people together in a way that felt very urgent.

At long last, we’re going to get some movement, despite what’s been happening in the last few years in Congress — some kind of rationality with the access to guns. Orlando and all the other mass killings have been an assault on the First Amendment, the right of assembly, and the right to association. And every one of the events that happened — whether it’s the African-American churchgoers in Charleston, or civic-minded people gathering to hear from their Congress Representative Gabby Giffords in Tucson, or little children in first grade in Newtown — Orlando was, again, a group that had a common bond. LGBT people celebrating who they are and in what would otherwise be a safe haven. Even the First Amendment, the bedrock democratic value, has restraints on it. The Second Amendment? No restraint. People on watch lists who are denied access to boarding a plane can go out and buy weapons of mass destruction, assault weapons. It’s madness. But the LGBT community has a history of activism, and a history of winning: “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” DOMA, and so forth. It’s galvanized the LGBT community.

What was your experience with gay bars when you were a young actor in L.A.?

My experience was a little different: There weren’t that many Asian gays, so when I was in a gay bar, I was usually the only one. I discovered them in my 20s. I remember the first one I went to: It was called One on Melrose Boulevard in L.A. It’s not there anymore. This was way back. I had walked down an alley and there was a red lightbulb over the door. I walked in and it was like a sleazy sports bar. Pool table. The bartender was good-looking.

They always are.

They always are. Some of these sports-bar bartenders usually aren’t — a little on the fleshy side. But there was a good-looking bartender and people. Some had their arms around each other or were being very intimate. It was a little scary, believe me, the access to it. I was very apprehensive, but there was that strange composure that keeps you going. I sidled up to the bar and started talking, and all my guards were down. I could be who I was. [After that], I remember I took a female friend to an industry preview screening [because] I’d be seen by people who would be employing me. So I was leading a double life. It was a sanctuary of sorts, but then — after I’d become a presence in these gay bars — this older guy said, “You’re an actor. You’ve got to be careful because they raid these places.” He told me that people were marched out, loaded onto paddy wagons, taken downtown to a police station, fingerprinted, photographed, names put on a list. That was terrifying.

Were there other closeted gay actors you knew of at the time?

I bumped into them in gay bars. In fact, he’s passed now so I can mention it. The actor that played Kirk’s son in Star Trek II and III. Blond, good-looking kid. I walked in, and here’s Merritt Butrick playing pool. I said, “Oh, Merritt. How are you?” “Hi, George.” It was very casual and natural, and we never brought it up on the set. It’s a little awkward, but we made it normal.

He passed of AIDS, and I saw him do a play near the end of his life. He had lost a lot of weight. It was a two-character play and an older man, an accountant who was very lonely, took him in. He played the part of a gay hustler. It wasn’t a love thing. They were two lonely people that connected and shared their lives, and Merritt was fantastic in it. It was a moving, deeply felt part. I was talking to the stagehands and they said, “That big scene where Merritt has this emotional breakdown, after that scene he would go offstage, and he had to lay down because he was so tired.” He was frail-looking. Shortly after that play closed, he passed. But he had to keep working, and he was wonderful.

In an as-told-to essay for Esquire, you said that coming out is always a process. What was it like at first?

I felt very alone initially. As a 10-year-old, I was discovering that I’m different in ways beyond just my Japanese face. I thought Marilyn Monroe was glamorous, but I wasn’t getting hot and bothered like the other guys were. But Tab Hunter, who was the good-looking, boy-next-door, blond movie star — he was exciting. I wanted to be a member of the gang, so you act the part and you date because all the other guys are dating. You double date. I acted my way through my teenage days, and then I was pursuing a professional acting career. That imposed that act on me even more. But there’s that feeling of aloneness. That I have to make my own way because, yes, I have this face and I have these feelings, and no one else feels them except other whites. And I wasn’t aware that Asian-American men felt like I did, so there was that aloneness there, too.

While you came out later in life, you came out publicly in 2005 — early in Hollywood, when it was still a very contentious issue. Were you concerned about how it would impact your career?

Yes, that’s why I was closeted. I desperately wanted my career, and I knew that if I came out, it would mean my career would be on the [decline]. But I said to Brad, “Here we are together, living a secret life. I want to relax. I want to be able to be me. I want to be able to speak out on issues that are viscerally a part of me.” [Brad and I] had a discussion. We decided not to talk to my agent or any industry people, that this was going to be our decision. I came out as gay and blasted Arnold Schwarzenegger’s veto.

What advice would you give younger gay actors who are concerned about what coming out would mean for their careers?

When I came out I was past the leading-man age, and my career flourished. Although, the guest roles I’ve done since then, more often than not, had me as Gay George Takei: Will & Grace, The Big Bang Theory. I played me, essentially, as gay. And that was my sole definition.

Do you think that was a problem?

Not for me, because that was the decision I made. I’m going to be on rally platforms talking about LGBT equality — why not in front of the television camera? I would say that actors need to think in terms of not being so fixed on a single image. We’re constantly changing, and that change will be imposed on you whether you like it or not. You’re aging. You’re growing materially, maybe losing hair. Sure, you can get a toupee as a lot of actors do, but you have to be creative with your professional image and deal with the realities of the changes that are happening to you. And so, you change with the forces.

What does your media diet look like?

The New York Times. I watch The Today Show in the morning, and I try to catch the nightly news. Meet the Press on Sundays. Sixty Minutes. And the internet.

How do you decide what to share on social media?

We’ve found through trial and error that humor is the honey that gets the most people, and as you know, it’s a sharing medium, so now I have a team. I think it’s 11 people. I couldn’t be doing this and the other things I do without a team to help me. We get a lot of people sharing memes, and we re-share, but we intersperse it with originals as well as occasional political commentary, which is really my area of interest.

Do you approve of every single one?

Theoretically, I’m supposed to. But there isn’t enough time in the day.

What was life for you like after Star Trek?

After Star Trek, I knew I wouldn’t get cast. All my colleagues from Star Trek complained about the same thing, except for Bill Shatner. He went into another series. Leonard [Nimoy] went into another series: Mission: Impossible. But the rest of us, we were remembered for the characters. Jimmy Doohan is always complaining, “They want me to have a Scottish accent.” Nichelle Nichols said, “They want me to be a space woman.” That image brands you, and producers are reluctant to have Uhura appear as a mother in a contemporary series. I knew that would be a given in my situation right after Star Trek, so I became more active in the political arena.

Are there roles you would like to play?

I would someday like to do Death of a Salesman. I suggested the idea to Tim Dang, the artistic director of the East West Players, because the values are very Asian-American: hard work, having high aspirations for your son, but being hypocritical about it, too. It’s a very Asian-American story and I think with an Asian-American cast, that would become more clear.

During your career, were there roles you took because you needed the work?

I had offers from Jerry Lewis to do some of his ridiculous comedy films. They were buffoon parts. I turned them down. My agent said, “George, you have an ascending career. It’s vitally important. Your movies have not been box office successes. Jerry Lewis is the biggest box office in Hollywood; it’s going to help your career.” The money wasn’t much. I was ambitious at any price, and the price was low, but I did it because of my agent’s persuasion — and he was a Japanese-American at that. So I did that, and then right after he gave me another offer and my agent said, “There you go! You’re on a roll. You’re doing another Jerry Lewis movie.” I regret both movies. Deeply.

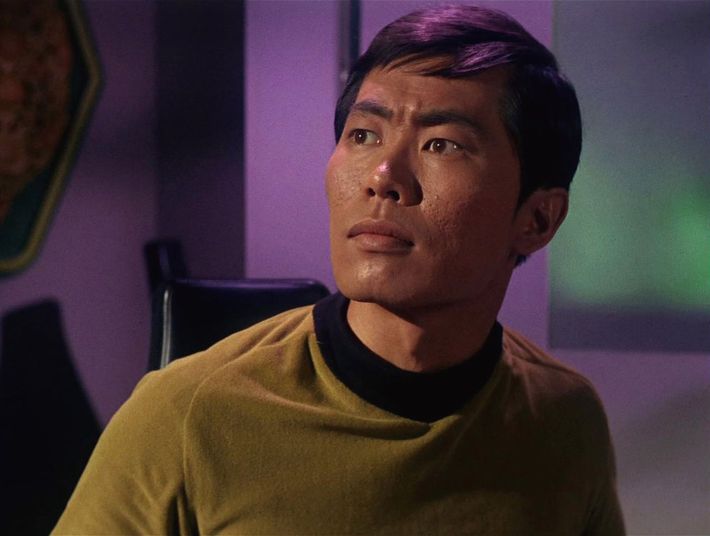

In The Big Mouth (above), I was an obsequious assistant to a scientist. I was thrown into a pot, and I’m screaming and yelling. The other one was Which Way to the Front?, where I played a Japanese soldier who couldn’t find his way. Sure enough, both movies were box office successes. Jerry Lewis was hot back then. But it didn’t change my career any.

Asian-American are in a difficult situation where they might need to take work, but the options are limited or demeaning.

They also need to be aware of the fact that those roles can color the rest of the roles you get. If you’re successful in them, like poor Gedde Watanabe, Long Duk Dong [in Sixteen Candles]. That was memorable. I’m sure he wishes it wasn’t remembered. The reaction from the Asian-American community was searing. He got scorched by it. So you’ve got to be very careful.

There has been a great deal of controversy around Asian-American roles recently — for instance, with Tilda Swinton’s casting as the Ancient One in the upcoming Marvel movie Dr. Strange. A lot of people were saying, “Well, you know, this is color-blind casting. Shouldn’t that be good?”

I’ll believe in color-blind casting when we have that kind of equity.

One of Marvel’s arguments has been that by casting a white woman in this role, they would avoid stereotype.

Their argument was sophistry. Pure sophistry. Why not bring a bit more humanity to that character that an Asian female actor would be able to bring? That becomes a richer viewing experience for the audience. And the other argument they use is, well, she’s a name and she’s box office. Yeah, it doesn’t guarantee success. One of my favorite films is Lawrence of Arabia. Peter O’Toole was a complete unknown in that movie. And because the producers took a chance and he did a fantastic job in it, he became a big box office star. Making a movie is a high-risk business. If you’re going to risk tens of millions of dollars, then be equally risky and cast Asians in Asian roles. And that person, if he or she is right for the role, will become a big star.

We had the Oscar nominations come out about the same time. It was all white people that got nominated, so the #OscarsSoWhite hashtag trended. The African-American community picked up on it, and we thought we would be a part of it, but when the Oscars show was actually staged, we saw it was black and white. Literally. When Asians appeared, we were again stereotyped and buffooned. It was outrageous. That isn’t diversity. So we had phone calls with each other and decided we were going to react. Then the Academy said, “Well, let’s have a meeting.” And so the Asian group met with the president and the executive director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

What was that conversation like?

We thought we made an impact. [Academy President] Cheryl [Boone Isaacs] was not argumentative, but rigid. [Academy CEO] Dawn [Hudson] was very impressed. She said, “Yes, yes. I can hear the searing feelings from you people.” We’ve been following up, but there’s been no real follow-up from the Academy. We’re going to get Asian-American members of the Academy onto various committees who can articulate our issues and concerns.

There were also reports that producers had done CGI testing on Scarlett Johansson to make her look more Asian in Ghost in the Shell.

Yellowface was the making-up of actors to look Asian; this is what they’re doing with CGI now. I worked with Alec Guinness in A Majority of One. He played a Japanese businessman who falls in love with a Jewish lady from Brooklyn, played by Rosalind Russell. They hired a Japanese-accent language coach and he had some Japanese dialogue, so the language coach was there to work with him. Alec ignored him completely. [The coach] said, “Mr. Guinness doesn’t want to use me.” And he used his own slurry idea of what a Japanese accent is, and I noticed he used the same accent in Passage to India when he played an Indian man.

What do you do in that situation?

It’s a fait accompli. I was hired for a small role in it. Mr. Guinness is in makeup, and he comes out looking like a reptile. He was supposed to be a warm character, and he played him as a cold aristocrat. We have a history of that sort of thing, and it’s being replicated now with CGI. We haven’t made any progress yet.

Why is it significant for you to have these conversations on Facebook?

We have a whole history of being stereotyped by that kind of casting, which has been enormously damaging. It put us, innocent Japanese-Americans, behind barbed-wire, prison-camp fences. That’s the most radical damage of stereotyping. The single most popular issue in California in the late ’30s, early ’40s, was to lock up the Japanese. And I’m using the long word for Japanese.

We had an attorney general in California — he was also an ambitious man who wanted to run for governor. So he decided to be an outspoken leader of that movement and he said, “We have no reports of sabotage or spying or Fifth Column activity by Japanese-Americans, and that is ominous because the Japanese are inscrutable.” That stereotype: You don’t know what they’re thinking, so it’d be prudent to lock them up before they do anything. The absence of evidence was the evidence. Stereotypes can be that damaging, and Hollywood still hasn’t gotten that message.

You’ve said that Allegiance, the Broadway musical set during Japanese-American internment that was inspired by your personal experience in an internment camp, was your legacy project.

It is a critically important part of American history that becomes more critically important because people don’t know about it, particularly on the East Coast. And because we don’t know about it, people like Donald Trump can make the kind of racist statements that he’s been making, whether it’s people coming from across the southern border or Muslims entering this country, painting all people with that one broad brush. It’s madness. And it’s dangerous.

And a lot of these histories aren’t really told within popular culture.

When we did Allegiance here, the ushers told me backstage during the intermission there were people having debates on, “Is this story true? Oh no, I can’t believe it. It couldn’t happen in the United States.” This is 2015 and 2016 and people are saying, “Is this story true?” That’s why it was so important for us to get that on Broadway, to tell it on that level.

Do you feel satisfied with its Broadway run?

No. I feel very fulfilled with the audience we had, but we had to discount the tickets severely, and it was not an economic success. They say smart actors don’t invest in their own productions. Well, I’m a dumb actor. We lost money on that. So in the show-business sense, we were not successful. But in terms of theater art, we were enormously successful. We had full houses almost every night, every performance. People came to see Allegiance and people wept. Lin-Manuel Miranda came to the opening and he tweeted, “Sobbing.”

Is there anything you would have done differently?

What could we have done? We used social media, first of all, to raise awareness of the internment. And when we reached a certain point, we introduced the fact that we’re doing this musical. There was tremendous excitement, but social media is global. So we did targeted ones for the Northeast, but people thought, it’s going to be a depressing story. Some people even thought it might be anti-American. I was shocked by that. It’s a controversial and embarrassing issue for America, that we did something not that dissimilar from what the Nazis did.

You filmed with Donald Trump on Celebrity Apprentice. Do you see much of a difference between his TV personality and his political candidacy?

The TV personality doesn’t require him to take stands on issues, so he presents an engaging image. As a political figure, he is crazy: off-the-cuff, insulting people, insulting his constituency, garbling what democracy is all about. He is a disaster, and the chilling thing is that so many Americans support him. That’s what reminds me of what happened to us during the Second World War. Americans can be stampeded, either by their economic circumstances or fear, and he’s playing on both of them. But I hope and pray that America, as a nation, will make the right decision.

What do you think of Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders?

I’m a Hillary Clinton supporter. I agree with a lot of things Bernie talks about, and he’s good at defining the issues, but not at finding solutions. He’s been in the Senate for years, decades, but what has he delivered? Hillary, in her rather brief tenure in the Senate, has been able to identify issues and make the appropriate adjustments and compromises with other justified concerns. She has a history of delivering. Bernie does not.

It was recently announced that Sulu will be gay in the upcoming Star Trek film, and my understanding was that John Cho was the one who talked to you about it. What was that conversation like?

I’m getting sick and tired of talking about the gay Sulu issue. There have been so many conversations I’ve had. John called me over the phone to tell me they were talking about making Sulu gay over a year ago. I said what would really be exciting, rather than taking a character that was consciously created — because all of the characters [Star Trek creator] Gene Roddenberry created were straight because of the nature of the times — would be to create a fresh character in the new, futuristic time. Shortly after that, I got a phone call from [Star Trek Beyond director] Justin [Lin], and I had a long conversation, and he listened very intently. After that hour-plus conversation we hung up, and I felt he had heard me. I didn’t hear anything until — well, until recently. A couple of months ago I got an email from [Star Trek Beyond screenwriter] Simon Pegg, who’s the co-writer on the project, and he wrote what seemed like an effusive fan letter, praising my courage and my dedication and my energy in my advocacy for LGBT equality. And so I thought, well, how nice, I’m getting a fan letter from Simon Pegg.

Then recently, I got a phone call from John again asking me to give him some guidance on how he should approach the PR tour for Star Trek. And I said, “Well, is Sulu still gay?” He said, “Yes.” And I said, “Oh, so all those conversations I had with Justin weren’t heard.” And I said, “Well, you know what my position is. You do what you have to do. Give your opinions.” And he says, “Well, I’m going to pay tribute to you.” And I said, “No, it’s not about me, it’s about Gene Roddenberry.” This is the 50th anniversary of Star Trek, and it’s eminently proper that we pay a tribute to him by honoring his brilliance as a storyteller, as a producer who had the courage to pound on those executives’ desks and be able to get a show like Star Trek on.

A lot of your argument seems to rest on the view that it’s not canonical.

No, it’s not that. Because they’re in another universe. I said be imaginative, create an original character that has a whole history of his own in his time.

Did you ever ask Gene for a gay character?

No, I asked him to address the issue, not create a character. I had a long discussion with Gene privately — I was still closeted then. Gene strongly supported the idea of LGBT equality, but he said the show that got us the worst rating ever was the one where we had the black/white kiss, between Kirk and Uhura — that hit rock bottom because it was blacked out in the South. They didn’t air it from Louisiana to Georgia. He said, “We’re walking a tightrope here. I’m pushing the parameters of what issues we can deal with, but I’ve got to stay on the air in order to deal with the issues. If I dealt with the gay issue, then I won’t be able to make any of those comments at all.” And I understood because of the times.

What do you think of the new Star Trek films?

They’re great action/adventure space operas, but they don’t have that Gene Roddenberry dimension. This is J.J. [Abrams]’s project now. So I shared as much as I knew about Gene’s philosophy, and how much I admired him. But that element isn’t in the two films I’ve seen.

What conversations have you had with J.J. Abrams?

When J.J. Abrams got the franchise, I got a phone call from his office asking me to have breakfast with him. He’s a very, very interesting guy, full of energy. He’ll pepper you with ideas that he has for the new version of Star Trek, but the reason he wanted to talk with me was he wanted to find a Japanese-American actor to play Sulu, because I’m Japanese-American. But he’d found someone [who wasn’t Japanese-American] he was interested in casting, and he wanted to know what I thought about that. I realized that J.J. really didn’t understand Gene Roddenberry’s thinking on Star Trek. Because from the casting of the original, you know that Roddenberry was using Starship Enterprise as a metaphor for Starship Earth, and my character was supposed to represent all of Asia. Gene’s challenge was to find a name for this Asian character because every Asian surname is nationality-specific: Tanaka is Japanese, Wong is Chinese, Kim is Korean. Because it’s the 23rd Century, he wanted a name that suggested Pan-Asia. He had a map of Asia pinned on his wall and he was staring at it, and one day, he found a sea called the Sulu Sea off the coast of the Philippines. And he thought, the waters of a sea touch all shores. And that’s how he came up with the name Sulu.

So I told J.J., “You know, that was Gene Roddenberry’s vision, Pan-Asia. So, is the person you’re thinking of Asian?” He said, “Yes.” And I said, “That’s all that matters. Can you tell me who he is?” He said, “John Cho.” And I said, “Oh, he’s a great actor.” Comforted by that, he went on to cast John, but the guru of the rebirth of Star Trek didn’t know that history of Star Trek and what the Enterprise stands for, and why the cast was diverse.

Will you watch Star Trek Beyond?

Of course. I want to make absolutely clear that I am thrilled, overjoyed, happy, ecstatic. My problem is with that Hollywood Reporter interview— the headline does not characterize the conversation I had. I do understand journalism — you need headlines that grab people. But that was misleading. I was not disappointed by the fact that they have a gay character.

Historically, Asian-American men don’t get love interests, and they’re often desexualized. Something about Sulu that always struck me was that he never had a love interest. Do you feel disappointed by that?

I always lobbied for that. Most actors, when they do a series, they go with the flow, but I saw this as a great opportunity, particularly because Gene was so receptive to ideas. I kept lobbying, not only Gene, but the writers and the directors to, for one thing, beef up Sulu’s role, but also give Sulu a family and a love interest and to make him more human. All you can do is lobby, and there are six other actors equally lobbying, too, that they’ve got to answer to, and we had two stars that had the loudest and strongest voices. The captaincy was something else I was lobbying for because this is a meritocracy. I became a lieutenant commander and a commander, but I’m still at that damn helm console, saying the same, “Aye, aye, sir.” And when it finally happened that I got the captaincy, it was not expected. I’d more or less given up by the 20th year of doing that. But being a political activist, I was always an activist with my career as well.

This interview has been edited and condensed.