Mr. Robot is one of the most pop-culture-fluent series on TV. Rather than merely recycle favorite references, writer-director Sam Esmail and his collaborators use their knowledge base to create a work that’s uniquely personal. This illustrated article about the style of Mr. Robot will look at a few examples from the season-two premiere, with commentary about how Esmail’s writing and direction help put them across.

Part of what makes Mr. Robot so enjoyable, whether or not the story is doing it for you at that moment, is that you can’t take everything in all at once. The show is directed within a millimeter of its life, and because Esmail’s script is driven as much by images and sound as by dialogue, the show’s directing is inextricably intertwined with its writing. Every shot, camera move, music cue, and cut has purpose, whether a given choice seems intended to convey an important meaning in the story (the hero’s mental state, the relationship of one character to another) or to add a visceral or “awesome” quality to what might otherwise just be a scene of people talking in a room. Although it’s far from a subtle show, and can be obvious in its borrowings, Mr. Robot is genuinely cinematic television in which the image is not a slave to the word, but its partner.

I’ve written elsewhere about how the core references are drawn from Cinema de Dudebro, a tradition of films that “absolutely pass muster as art while also just happening to look and sound frickin’ awesome when you put them up on that 57-inch plasma screen with surround sound that hangs on a wall opposite your black leather couch”: the original Star Wars trilogy, Stanley Kubrick, David Fincher (especially Fight Club), David Lynch, and Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver in particular — one of the great unreliably narrated films, and one of Esmail’s acknowledged influences).

Esmail is up front about the art that has fed his imagination. The most widely discussed example is from season one, when the show’s hacker hero, Elliot Alderson (Rami Malek), realizes that the title character (Christian Slater) is a figment of his derangement, à la Tyler Durden in Fight Club, in the form of his father — a twist that many viewers, including yours truly, didn’t care for (even though it’s grown on me, thanks in large part to what the show appears to be doing with it in season two). Esmail brings in Maxence Cyrin’s piano version of the Pixies’ “Where Is My Mind,” Fight Club’s closing-credits song, as if to say, “Yes, I saw it, too — and I’m not pretending I didn’t.” As Esmail told Vulture last year, Kubrick’s oeuvre informs the series as obviously (and playfully) as the Coen brothers’ filmography informs Noah Hawley’s TV riff on Fargo. In addition to the hero’s A Clockwork Orange–style narration and the bold placement of the title logo in every episode, there are examples of what you could call Stanley Kubrick Easter eggs — such as Darlene’s glasses, which resemble Sue Lyon’s specs in Lolita, and the masks worn by fsociety members, a nod to Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut. Likewise, they may also remind you of the mask worn by the title character of V for Vendetta, a Wachowskis-produced cyberthriller based on David Lloyd and Alan Moore’s comic about a terrorist/freedom fighter attacking society’s ruling structure.

Although they have almost nothing else in common aesthetically, Esmail’s attitude toward this stuff is reminiscent of both Quentin Tarantino and Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner, in that he’s obvious and subtle at the same time, and the references are numerous and multivalent. Consider the hero’s name, which nods at more than one source: “Elliot” is spelled the same way as the hero’s first name in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, about a do-gooder who tries to change society and is presumed to be insane; it’s one t removed from that of the hero of E.T., a movie about a troubled boy’s relationship to a special friend; and Elliot’s last name is one consonant away from “Anderson,” the last name of the hacker hero of the Wachowskis’ The Matrix trilogy. Elliot’s sidewall haircut, meanwhile, brings to mind Travis Bickle’s mohawk cut in Taxi Driver. These are references that, in almost subliminal ways, build your sense of this character.

A richer example of the show’s layer-cake approach can be seen in the second half of the Mr. Robot premiere, when Evil Corp’s CEO Philip Price (Michael Cristofer) refuses to resign his position to please high muckety-mucks working for the Department of the Treasury. “Every business day when that market bell rings, we con people into believing in something,” he tells them, with undisguised contempt. “The American dream, or family values. Could be freedom fries, for all I care — it doesn’t matter! As long as the con works and people buy and sell whatever it is we want them to.”

It’s a long speech even by the standards of Mr. Robot, a series that’s not shy about asking its actors to make wordy monologues sound natural. The setting — a creepy cavelike space where slightly abstract “powerful” figures hold sway — evokes two classics of 1970s American cinema: Sidney Lumet’s 1976 satire Network (scripted by Paddy Chayefsky, an unrepentant speech-aholic) and Alan J. Pakula’s 1974 paranoid thriller The Parallax View, in which Warren Beatty’s investigative journalist tries to expose a corporation hired by elites to stage political assassinations. Price’s monologue to the board is reminiscent of the four-minute speech in Network that TV fat cat Arthur Jensen (Ned Beatty) delivers to news anchor Howard Beale (Peter Finch), about how “there are no nations” anymore, only an international network of forces united by greed. And in the most direct reference, as Mr. Robot’s Price becomes more arrogant, the episode brings in a music cue from Michael Small’s Parallax View score, “Commission and Main Title.”

Every now and then, Mr. Robot’s pop-culture references feel like a slightly mysterious private joke, even when they’re working to ratchet up emotion in a scene. My favorite instance is the first scene in the second half of season two’s premiere, when Evil Corp CFO Scott Knowles (Brian Stokes Mitchell) obeys fsociety’s orders and burns a heap of money in Battery Park City. Soon after it starts, we hear Phil Collins’s “Take Me Home” playing from a nearby boom box. But when Knowles sets the cash ablaze, the sound mix shifts. The Collins song quits being ambient music, filtered to sound as if it’s coming from a source within the scene, and becomes soundtrack music that dominates the action.

In addition to its storytelling function, this money-burning scene is a shout-out to writer-director-producer Michael Mann (Manhunter, Heat). Mann has a knack for using pop music to make what might otherwise have been an intense but quiet moment feel operatically big. His stylistically innovative cop show Miami Vice used this same piece of music in roughly the same spot in its episodic timeline: in the season-two opener where detectives Crockett and Tubbs go to New York to work a case — you can watch it on Hulu here — fast-forward to the last four minutes.

As we’ve seen, Esmail italicizes a lot of his borrowings in the manner of a collage or pastiche artist rather than trying to disguise or alter them. But these rarely feel like “too much” because the show’s direction (done exclusively by Esmail in season two) celebrates too-muchness. The filmmaking is showy and bouncy — part of the sub-tradition of the director as performer, entertaining the audience with clever, surprising, or ostentatiously difficult camera moves, in much the same way that extremely physical actors might engage the audience by doing broad but undeniably impressive things with their faces or bodies.

The tradition of director-as-performer extends far back into film history. It includes such auteurs as Alfred Hitchcock, the “Archers” team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, and Orson Welles. But Cinema de Dudebro recognizes Kubrick as the origin point for the director-as-star, a way of making films that’s exemplified by subsequent directors like Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Paul Thomas Anderson, Gaspar Noé (Irreversible), and Danny Boyle (whose heavily narrated, dryly funny Trainspotting is a clear influence on Mr. Robot’s music montages). These are all directors who aren’t shy about letting you know there’s an exuberant personality telling the story — a narrator who “talks” to the audience directly, in much the same way that Elliot talks to viewers of Mr. Robot. Rather than tastefully hang back, a director-as-performer might follow a character into a pool in a blatant reference to Mikhail Kalatozov’s I Am Cuba, as Paul Thomas Anderson does in Boogie Nights, or twist the camera 90 degrees or upside down to convey a character’s disorientation or a jump in time, as Scorsese and De Palma do in innumerable films, and as Noe does repeatedly in Irreversible.

Esmail does his own version of the acrobatic camera-twist in the opening section of Mr. Robot’s season opener. When young Elliot falls on snowy ground after being pushed out of a second-story window by his father, the shot starts on a close-up of the boy (1), then cranes up as his parents enter the frame (2), twists around toward the family’s house while continuing to rise up toward the broken window (3), and finally enters the window itself (4), the gloomy interior beyond the window frame creating a “cut to black,” which Esmail uses to transition out of this scene and into the next one.

Then we’re in an exam room at a hospital, where Elliot is diagnosed with an unspecified injury (probably a concussion) that may have gone untreated due to the parents’ financial distress. The blackness of the interior of the Aldersons’ home in the previous scene becomes an EKG screen. This sets up another of this prologue’s long, uncut takes (by this point in the episode, three minutes in, Esmail has used only three shots). The scene ends by moving away from young Elliot and past the doctor as the sound fades out and is replaced by muffled noise (perhaps suggesting what Elliot perceives), before settling on a brain scan that’s viewed from so close in, its patterns become abstract.

And here we arrive at my favorite transition in either season of Mr. Robot: a cut to a series of similarly abstract patterns that jump back in distance just a bit with each cut. The sequence eventually reveals that we’re looking at the cover of present-day Elliot’s composition book, in which he journals about his life while disengaging from the internet and living with his mom, supposedly (read an elaborate and persuasive theory about the “true” narrative of this season by my colleague, Abraham Riesman, here).

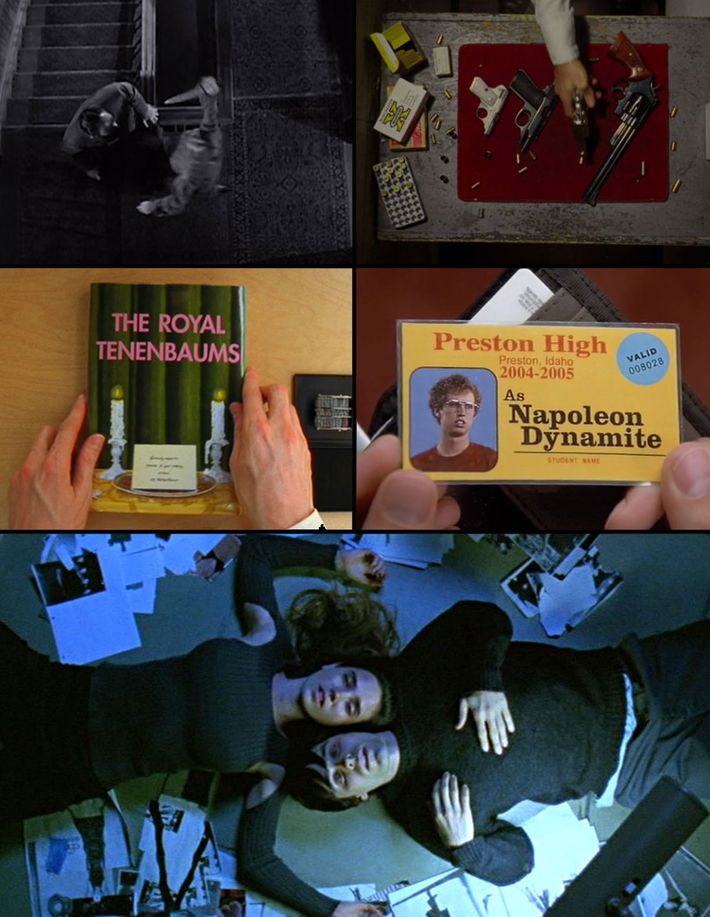

The god’s-eye-view framing of these inserts traces a line of visual influence. It stretches from Alfred Hitchcock (Psycho) through Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver) and into the recent past, via such directors as Wes Anderson (The Royal Tenenbaums), Jared Hess (Napoleon Dynamite), and Darren Aronofsky (Requiem for a Dream).

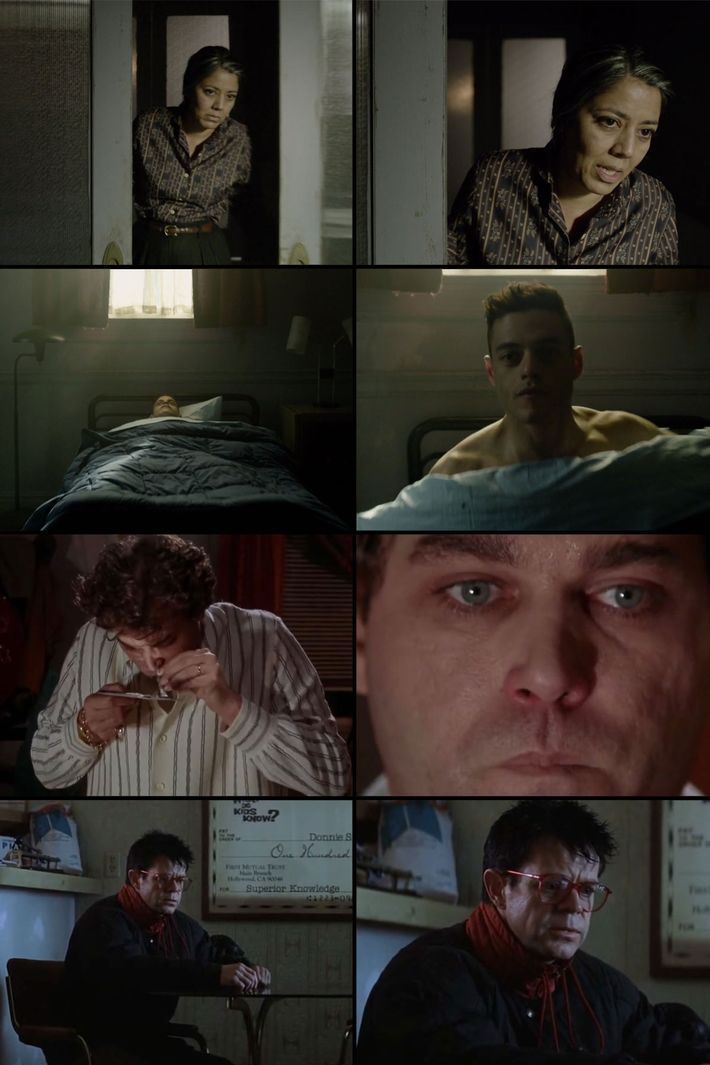

Esmail drives the Scorsese allegiance home with god’s-eye shots of Elliot lying in bed, seemingly paralyzed or nearly catatonic. The images are reminiscent of overhead views of crime scenes and alienated characters in Scorsese films, including Taxi Driver and Goodfellas, angles that themselves are modeled on god’s-eye images from Hitchcock movies Scorsese saw as a young man.

Even the specific way the camera lunges toward Elliot’s mother and then Elliot himself indicates a line of cinematic influence: Scorsese used this type of camera move to make ordinary reaction shots “pop” more, and Scorsese acolyte Paul Thomas Anderson copied them in some of his own early films, including Magnolia.

It’s no wonder Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner is a fan of Mr. Robot. Like Weiner’s masterpiece, Mr. Robot is about the people and events that it’s about while also celebrating the popular culture (movies especially) that informed its creation. You don’t need to be aware of the chain of influences to enjoy the story; the show’s default mode might be described, in software terms, as a “hide footnotes” option. But it’s still fun to root out the bits and pieces that went into the creation of this series, a conspiracy-thriller-satire-psychological drama that’s also about the anxiety of influence, centered on a present-day lost soul who’s trying to figure out who he is and how he got to be that way.