HBO’s legal thriller The Night Of is one of the most frustrating dramas in recent television: imaginatively acted and directed but inconsistently written; thoughtful and surprising in many ways but clumsy and occasionally inept in others. Although many of my colleagues have praised it, and I reviewed it enthusiastically based on viewing the first three episodes, I found my enthusiasm ebbing a bit more with each week, not because of the slow pace or overall gloominess (both qualities seemed organic to the material) but because The Night Of did extraordinarily difficult things with confidence and grace while neglecting basics.

The series started out strong, with a nerve-wracking premiere that put you in the shoes of its future defendant, Nasir “Naz” Khan (Riz Ahmed), and followed him as he was arrested for the murder of a troubled young rich woman named Andrea (Sofia Black D’Elia) and placed in Rikers Island jail awaiting trial. It took its sweet time introducing other major players — defense attorney Jack Stone (John Turturro), his partner Chandra (Amara Karan), district attorney Helen Weiss (Jeannie Berlin), NYPD police detective Dennis Box (Bill Camp), and Naz’s jailhouse protector Freddy Knight (Michael K. Williams), an ex-boxer now running a drug ring.

Series creators Richard Price and Steve Zallian drew much of their inspiration from classics of 1970s and early ‘80s urban potboilers: Serpico, Prince of the City, Fort Apache: The Bronx, and the like; the cinematography, by regular Paul Thomas Anderson collaborator Robert Elswit, was either bold or mannered depending on your taste; but it strongly communicated key ideas — chiefly the oppressive indifference of the state toward all of its citizens, the poor especially, and the way that the criminal justice system seems to operate adjacent to the society it supposedly protects, instead of feeling like an integral, invested part of it. Characters were constantly being squashed into the sides or pushed into the deep backgrounds of compositions, as if the world wanted to crush the life out of them, or barely noticed their existence.

But the characters pulsed with life anyway, and the show’s performances were often richer than the material the actors had been given to play. Ahmed nearly succeeded in giving us glimpses of Naz’s interior life, despite the blinds being drawn the whole time; Paul Sparks made the most of a one-note role as Andrea’s stepfather, a gold-digging fitness instructor, suggesting the self-loathing and depression lurking beneath his douchebag hatefulness; Jeannie Berlin’s Helen Weiss was the world-weary, taken-for-granted professional incarnate, arrogant in ways that the character didn’t fully grasp until the end, and more playful in court than you might have anticipated; the hangdog Turturro is already a national treasure by this point, but he would make a superb Columbo should anyone be foolish enough to attempt a reboot. Amara Karan deserves a medal for making an incoherent character seem almost coherent.

In time, though, the show’s incidental pleasures couldn’t counteract its deeper failures as a story. By the midpoint, it became clear that what we were seeing wasn’t a 21st-century urban tapestry invoking Dostoevsky or Dickens, but something more along the lines of AMC’s similarly neo-noir-inflected remake of The Killing, which likewise carried itself like a visionary, revelatory, searing examination of crime and punishment in the modern age, while delivering something closer to a single episode of a network crime procedural extruded to fill a season.

The most inadvertently revealing scene in the HBO series was the one in the copy shop, where an employee asked Stone if he was making blueprints for an episode of Law & Order. Intentionally or not, this felt like a snide dig at what the writers considered an inferior form of TV drama, even though Law & Order rarely did anything as dumb as having a second defense attorney and a defendant share a furtive kiss in a holding cell despite surely knowing on some level that a camera would capture it, and that the video might be used to ruin them later. Like many elements in The Night Of — including Stone’s eczema, which was handled more sensitively here, though perhaps excessively at times — this was imported from the British series, Peter Moffat’s British series Criminal Justice. Zaillian and Price made a number of intriguing and ultimately rewarding changes, such as making the protagonist a Pakistani-American (the defendant in Moffat’s series was a white man played by Ben Whishaw) but retained others, many of them puzzling. What is a remake, if not a chance to correct a beloved original’s missteps?

Naz’s opaque personality started to seem like a narrative cop-out after a while: If you’re denied meaningful insight into who the man is, or was, or what he might ultimately want, you can embellish his story with all manner of sudden reversals and revelations, confident that the audience can’t object that they’re nonsensical. The stories surrounding Naz — his defense and prosecution — were likewise filled with twists that seemed to come out of nowhere. These left us wondering if what we were seeing was a portrait of a broken system in which police, prosecutors, and defense attorneys were so overworked or incompetent that they couldn’t do their jobs well, or a TV series about the justice system that held certain facts in reserve to create surprise, even though they would have come up much earlier in a real trial with details as lurid and spectacular as this one’s.

Why didn’t anyone associated with the case think to investigate ownership of the murder victim’s house, and find out if there was anyone associated with the victim who might have a claim on it, until deep into the trail? Why did it seem to take forever for the defense team and the chief detective alike to realize that they could gather crucial evidence by studying surveillance recordings from all over the city on the night of the murder? Why wasn’t the chief detective studying the victim’s cell-phone records at length from the jump, instead of waiting until the end of the trial to pore over them, by which point he was already retired? How could Naz be on trial for stabbing a woman 21 times, yet nobody wondered why he had no blood on him until close to the end of the story? And is it really believable that Naz would have given himself over to prison life so wholeheartedly, convincing his attorney to smuggle drugs for him and coolly participating in jailhouse violence, to the point where (in the finale) he seemed poised to take over for Freddy someday? And was it necessary to make nearly every male African-American character seem like either a noble beast or a heartless savage?

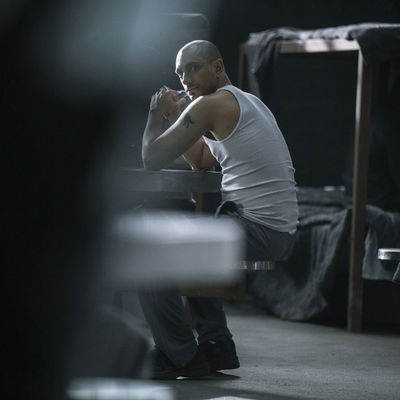

A bit more information, or a wider context, might have made such complaints moot, but we didn’t get as much of that as we should’ve. The Night Of was magnificent in bits and pieces, and there were sublime moments of character interaction, such as Stone gradually negotiating his fee downward with Naz’s parents, and Freddy telling Naz that he protected him because he thought he was a truly innocent man and therefore “a unicorn,” and Helen bantering with a smug forensics expert in court. And some images in the post-verdict ramp-down were as haunting as the entire series seemed to aspire to be: the bald, tattooed Naz doing drugs by the water and imagining Andrea there beside him (did he fall in love with her in his imagination?); Stone leaving his apartment to take on another case, the camera lingering on the closed door for just a moment before the cat crossed the frame. But the series could have been so much more. Greatness was within its grasp, but it too often seemed to get distracted by whatever was in front of it at the moment.