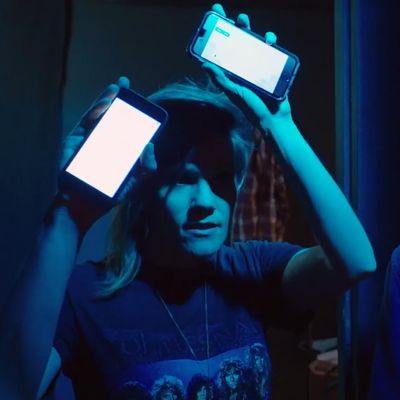

Early in the second, and by far the best, episode of Take My Wife — the new semi-autobiographical Seeso comedy created by and starring comedians and spouses Cameron Esposito and Rhea Butcher — Cameron and Rhea (note: first names mean the characters; last names mean the real people with the same name) are chatting beside the stage at a stand-up show they host together. As they watch a male comedian named Kent (played by stand-up Joe Derosa), Rhea asks Cameron, “Can Kent even do less than 20 minutes? I haven’t seen him do it?” Cameron agrees and asks for her phone. She proceeds to hold up two cellphones with their screens lit up (as you can see above). When Kent doesn’t respond, Cameron goes, “Come on, nothing? Nothing on double lights!”

If you don’t get it, that’s because this is a very obscure joke. It’s a reference to the politics of giving a comedian “the light,” which is the name for flashing a light to communicate it’s time for a stand-up to wrap up their set. In comedy clubs, there is usually a bulb behind the audience that’s flashed; in indie shows, hosts tend to hold up a phone. It’s something that happens in essentially every comedy show, every night in this country. If you’ve never noticed, watch a comedian around eight or so minutes into a ten-minute set (or twelve into a fifteen) — they will make a brief, discreet nod to tell the lighter that they acknowledge them. It’s a secret, unspoken language between comedians, and it’s what I loved about that moment in Take My Wife — it is one of the most inside-baseball comedy jokes ever put onscreen.

Think of the least sitcom-y moments of The Office: An American Workplace and how they spoke specifically to what it’s like to work in an office. This is Take My Wife’s version of that, but, in this case, the office is a stage and greenroom. Over the years, films and TV shows depicting this world have grown in specificity, and Take My Wife’s “double lights” joke captures just how much comedy itself has become a subject of examination on television.

There’s a long, varied history of this on the screen. Bob Fosse’s 1974 Lenny Bruce biopic Lenny, Martin Scorsese’s 1983 classic The King of Comedy, and Richard Pryor’s 1986 semi-autobiographical Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling established the comedian as a subject worth exploring. The 1988 movie Punchline, starring Tom Hanks and Sally Field, spent some time discussing stand-up as a craft that you work at, but it wasn’t particularly good or popular. It’s Garry Shandling’s Show premiered in 1986 and was tremendously influential. While it ran for four seasons, it was never a breakout hit and it can be argued that it was more interested in Shandling as a famous person than as a comedian. But it ultimately set the table for the game-changer in this sub-genre. “Seinfeld was our generation’s beacon calling us all together,” comedian Pete Holmes told me for my piece about the show’s influence on modern comedy. “It was like a Comic-Con for comedy dorks that you didn’t have to leave the house for.” The series created a generation of people who eventually grew up to became fascinated by comedians and the specifics of their lives.

Seinfeld, along with early 2000s documentaries The Aristocrats, The Comedians of Comedy, and the Seinfeld-starring Comedian, paved the way for the era of comedy about comedy. Since 2006, but in a big way since 2009, when WTF With Marc Maron premiered, comedy is opening itself up to its audience, revealing more and more about what it’s like to be a comedian. Judd Apatow’s 2009 film Funny People had its flaws, but what worked were the intricacies of how he depicted a group of friends all starting out in comedy together. Then in 2010 came Louie, and while it’s a show about many things, one of those things includes a much more realistic depiction of being a stand-up than we’d seen before. Take the heckler scene from season one:

Not only did Louis C.K. depict a heckler in a more nuanced, human way than Seinfeld did, but he has his character explain specifically why comedians find talking during the show so frustrating. From there, largely because of the success of Louie, comedies about comedy were everywhere.

Before Take My Wife’s doublelights bit, a scene from Mike Birbiglia’s recent film, Don’t Think Twice, felt like the benchmark for real depictions of being a comedian. The film follows a six-member improv group, and there’s a moment where they all gather to watch Weekend Live, the film’s version of Saturday Night Live. If you’ve ever watched or even talked to a comedian about SNL, the scene is uncanny. When I interviewed Birbiglia last month, he said his dream for the movie is that some people will think it’s a documentary. This level of verisimilitude is where comedies about comedy are at.

And it’s continuing. This summer, I visited two sets: Kumail Nanjiani’s Apatow-produced film, The Big Sick, and Pete Holmes’s Apatow-produced TV show, Crashing. Both are about their time starting out in stand-up, and considering they started out together in Chicago and moved to New York around the same time, the two projects are thematically similar. The scene of Holmes’s show I watched focused on him approaching a table of comedians. In some takes, he specifically calls it “the comedians’ table,” signifying to people in the know that it’s a version of the infamous table comedians hang out at the Comedy Cellar. By now, comedy fans have heard Marc Maron talk about it for years and they’ve taken it in. Making these sort of casual references to esoteric lingo is reflective of what it means to be a comedy enthusiast in 2016. Whereas in the past, a comedy fan was defined by watching comedy, he or she is now defined by an interest in learning about it. They know what the light is, and they even know the comedians who are known for frequently “blowing the light.”

Take My Wife is filled with little moments like this. More than any other example in this piece, it’s explicitly what the show is about. Esposito spoke with Scott Aukerman (who is a producer on the show) on his Comedy Bang! Bang! podcast and she described how her show differs from Louie and Maron: “[My and Rhea’s] relationship is just assumed — it’s the given — and what we’re trying to figure out is how to have comedy careers.” This is a big shift from the way shows about comedians worked in the past. Previously, the reason to make a comedian the protagonist of a film or TV show was because he or she ostensibly had free time to get into shenanigans. Now, we’re beginning to treat comedy as a workplace that fuels the drama, while personal relationships are just the color. By sharing the secrets of their trade, the stand-up comedian has basically become just another job in the eyes of comedy — it’s just as easy to believe a young person would make a living as a comedian as they would as a sports journalist for a local paper. Actually, considering the state of local papers, comedian is more believable.