Spoilers for Stranger Things below.

The crystal-clear subtext of NetflixÔÇÖs beloved Stranger Things is an argument that there was something special about the horror and sci-fi filmmaking that emerged in the 1980s. But commentators have more or less taken for granted the notion that the pieces from which the Duffer Brothers lifted came from the U.S. That makes sense, given that all eight episodes are profoundly steeped in the peculiarities of small-town Americana. But in the middle of the first episode, a single Japanese name started ringing in my mind like the psychic echo of a tortured telepath: Akira! Akira! Akira!

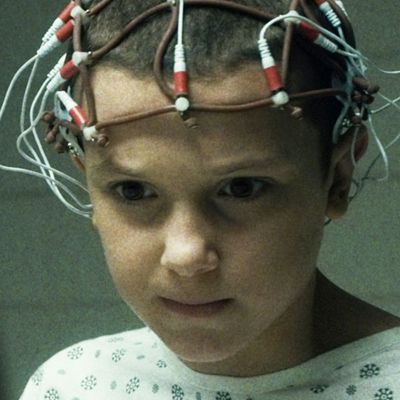

I canÔÇÖt be the only one who thought of Katsuhiro OtomoÔÇÖs 1988 anime masterwork, right? From the first moment that a shadowy government official refers to an escaped youngster, the hairs stood up on the back of my neck. Right after that, we see that escapee, hair short, wearing a hospital gown, stumbling aimlessly. We soon learn that this kid possesses miraculous telekinetic and telepathic abilities, ones the state analyzed while keeping her under lock and key in a sterile facility. She was being trained as a tool but was just as effective as a weapon, occasionally turning on her captors by murdering them in hospital-like hallways with a flick of her brain. Her flight from captivity sends the agency that held her ÔÇö especially a stern father figure who directed the whole operation ÔÇö into a flurry of panic. But all she wants is to navigate her adolescence on her own.

Of course, as anyone whoÔÇÖs devoured Akira or its manga source material (also made by Otomo) can tell you, all of those things run parallel with that operatic cyberpunk tale. The character of Eleven feels like a kind of mashup of a few figures from the story: her diminutive size and angelic face recall the apocalyptically powerful title character; her frightened demeanor and aggressive pursuit suggest Takashi, the first superpowered character we encounter; her centrality to the story and quest to figure out life as a teenager make her seem like anguished co-protagonist Tetsuo. Matthew ModineÔÇÖs Dr. Brenner feels a lot like a more placid version of Colonel Shikishima.

But IÔÇÖm getting ahead of myself. If youÔÇÖve never seen Akira, its basic outline is as follows. After a mysterious event leveled Tokyo and kicked off a world war, the Japanese build a technologically advanced neo-Tokyo next to the ruins. One fateful night, a teenage motorcycle gang rides into the old city and one of their members, an angsty teen named Tetsuo, crashes into a force field created by an unearthly looking child, Takashi, and gains his own unique abilities. What follows is a byzantine and horrifying trip down the rabbit hole, one where Tetsuo finds himself analyzed by a government agency tasked with training gifted children, then escapes and nearly destroys the planet. All the while, TetsuoÔÇÖs friends and erstwhile captors battle to keep him from each other.

In Japanese entertainment, Akira was epochal, influencing manga and anime in countless ways big and small. But for some reason, despite its cult status on this side of the Pacific, itÔÇÖs never bled all that much into American entertainment. ThatÔÇÖs a damn shame, because thereÔÇÖs so much to draw from: the visuals of tested-upon young people ominously gazing forward and making the world move at their behest, violently visual metaphors about the horrors of hitting your teen years, gorgeously designed techno-bikes, a giant orbital space-laser, and cityscapes that make Blade Runner look suburban.

Kanye West knew this, and thatÔÇÖs why his 2007 video for ÔÇ£StrongerÔÇØ is roughly 90 percent comprised of direct Akira references (Ye has said itÔÇÖs tied for his favorite movie of all time alongside another vision of power gone mad, There Will Be Blood). Rian Johnson, too ÔÇö his underrated Looper features a telekinetic child on the run from bad guys, and the visual representation of his abilities is very clearly Otomo-inspired.

Instead, AkiraÔÇÖs biggest influence on this nationÔÇÖs film industry has been more than a decade of threats that there will be an Americanized, live-action remake. Justifiably, critics have derided the notion as an example of race-bending ÔÇö taking an East Asian story and refilling it with white actors. But why remake it when you can simply borrow from it? The original had many distinctly Japanese traits, particularly the idea of rebuilding after an Armageddon-level explosion. You can make a solid argument that it would be nonsensical at best and disrespectful at worst to try and transport the action to, say, a post-apocalyptic New York.

Instead, much as Star Wars served as a kind of thematic template for something like Guardians of the Galaxy, one can fantasize about a movie that takes from┬áAkiraÔÇÖs overbuilt setting, dystopian bikers, and ominous tones of coming disaster at the hands of a youngÔÇÖun. Even just the latter is enough to titillate ÔÇö you may not have ever heard of OtomoÔÇÖs opus, but can you deny that ElevenÔÇÖs laboratory flashbacks and power demonstrations were some of Stranger ThingsÔÇÖ finest moments (well, at least of the ones that didnÔÇÖt involve the perfect Barb; RIP, mourn ya ÔÇÿtil I join ya)? ThatÔÇÖs the kind of stuff Akira mastered. One canÔÇÖt prove that the Duffers were looking to it, but one can hope future filmmakers will.