This piece originally ran in 2016. We are republishing it on the occasion of The Suicide Squad’s release and Viola Davis’s return to the big-screen role.

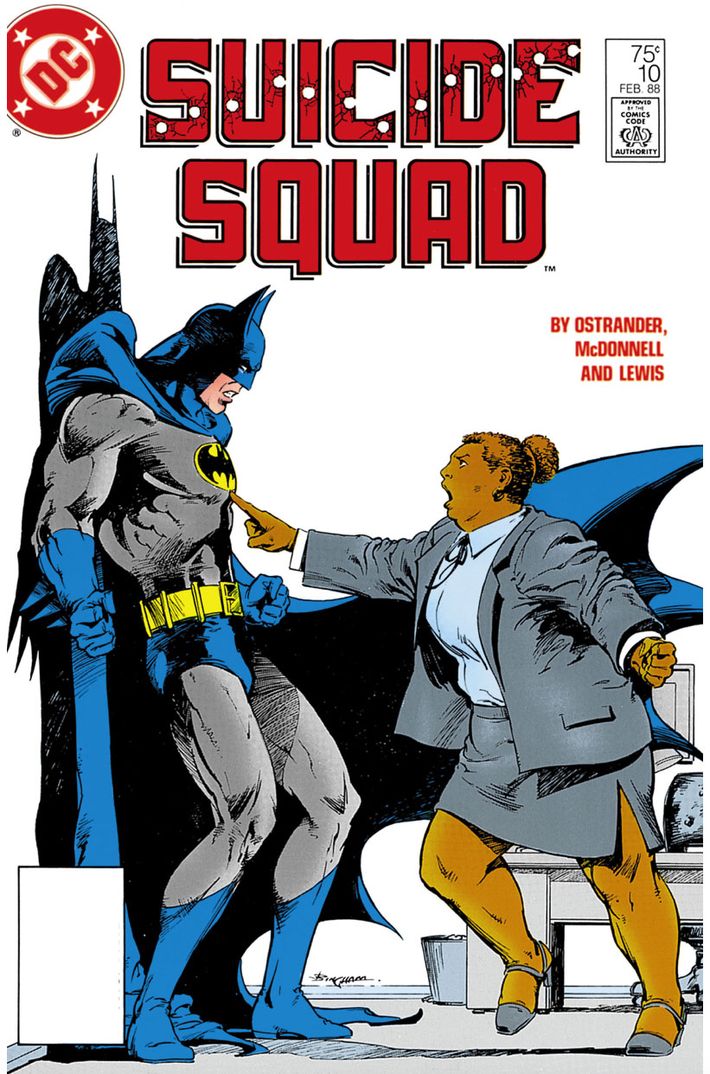

Comics commentator Ardo Omer’s voice swells when she remembers the first time she came across Amanda Waller, the hard-ass leader of the Suicide Squad. It was in the mid-’00s, during an episode of Justice League Unlimited, a cartoon starring DC Comics characters that aired two decades after Waller debuted in DC’s Legends mini-series. “The first thing you see is Amanda Waller’s presence, the way she moves, even before she speaks,” recalls Omer, who is black. “She was this short, big, black woman — the kind of woman I’d grown up seeing in my neighborhood, calling them ‘aunties’ even though they weren’t related to me. And she was standing up to Batman!” Omer was in awe.

That moment is a decent encapsulation of what makes Waller groundbreaking in the annals of superhero fiction. When she was created in the mid-1980s by writer John Ostrander, she was explicitly supposed to be unlike any other comics persona. In a genre where women are drawn as pin-ups and black people are often either pure-hearted role models or streetwise hoodlums, she was — and is — something different: a middle-aged, heavy-set, profoundly cynical, African-American, female government apparatchik. She’s calculating, contradictory, and confrontational. She shouts down presidents and spandex-wearing crusaders. She’s had rare staying power, and that’s in no small part due to the progressive aims of her creator — aims that were, for a time, betrayed in a way that made her nearly unrecognizable.

At the time of Waller’s creation, Ostrander was on an unusual path for a comics writer, having only entered the business in his mid-30s. Prior to that, he’d studied to be a Catholic priest, driven a cab in Chicago, and had a reasonably successful career as an actor and playwright there. A longtime comics fan, he turned his pen to that medium in 1983 at the behest of a theater friend named Mike Gold, who was launching a small company called First Comics. Ostrander’s work there, most notably on an outlandish sci-fi series called Grimjack, earned the admiration of a DC editor named Bob Greenberger. Around 1985, Greenberger floated the idea of Ostrander doing a series for the company, and Ostrander suggested resurrecting a team from the 1950s called Challengers of the Unknown. That group had already been claimed for a project, so Greenberger suggested another DC property from that period: the Suicide Squad.

“My first reaction was, ‘Suicide Squad’? What a stupid name for a book,” Ostrander recalls. “Who would knowingly belong to something that called itself ‘Suicide Squad’?”

It’s unsurprising that he was unfamiliar with the name — the team had only appeared in a handful of issues of the mid-century DC series The Brave and the Bold. They were a military group sent on particularly difficult missions, created by writer Robert Kanigher (who stole the name from a Nazi-fighting gang that appeared in a few World War II–era pulp magazines) and artist Ross Andru. It disappeared and was largely forgotten.

But as Ostrander pondered, he thought of the type of person who might join an organization with that moniker: “Maybe people who didn’t have a choice. Well, who doesn’t have a choice? Hmm. Prisoners! Prisoners don’t have a choice. Okay. And that means in the [DC universe] that we’re talking about supervillains, and I like villains, I always have.” He’d long been a fan of espionage stories and thought the team could be working for the U.S. government on secret missions against their will. That meant an operative would have to keep the project in line, “ramrodding it,” as Ostrander says.

Once he’d come to that conclusion, Ostrander’s self-identified “left of center” leanings came into play. “To start off, I wanted someone who is African-American, because at the time there weren’t as many African-American characters in comics,” he says. “And I wanted the character to be female because we didn’t have very many female characters, either, ones who were very strong and could basically kick ass. And I thought she should be a little bit older, because I wanted her to have a life story, something that fed into who she was.”

As the character percolated, he cooked up a name, Amanda Waller, and a nickname branched off in his mind: “The Wall.” “When you’re doing comics, you need a visual shorthand in order to convey certain aspects of a character,” Ostrander says, “and if Amanda Waller’s nickname was ‘The Wall,’ she had to look a little bit like a wall. She had to look formidable. By not giving her Wonder Woman’s muscles, and instead some heft, it sort of suggested a power in her.”

When all those pieces were put together, the resulting picture was unlike anything in superhero comics at the time — or really, even in them now: a leading lady who was stout, black, and getting along in years. He didn’t want her looks to define her, but he knew the power they held. “With her very existence and presence, she made all the points that I wanted her to make,” he says.

Ostrander brought the notion of Waller and her Squad to Gold, who had started working as an editor for DC in 1985, and the pair began having creative meetings at Gold’s paper-cluttered apartment in the Chicago suburb of Evanston. They knew they were sort of ripping off the basic concept of The Dirty Dozen, the 1967 film about a military officer played by Lee Marvin leading a group of misfit prisoners on a dangerous mission. But the world of superhero comics is a place with a long tradition of ripping off outside influences (most infamously, Batman began as a more or less direct lift from pulp hero The Shadow), and there was enough here that would be different to set it apart. Waller was a big part of that. “She was Lee Marvin as an overweight, black female,” says Gold with a laugh.

There was one last component she needed: a backstory. For that, they turned to their city. One of the most crime-ridden parts of Chicago at the time was a housing project on the Near North Side called Cabrini–Green. “If you’re white, you never spent much time in Cabrini–Green, I’ll tell you right now,” Ostrander recalls. That is, unless you were a progressive activist like Mike Gold had been.

“I went there a lot,” he says. “I did some drug-education work there, I was involved in some protests there. We were involved in a couple of projects about what was, at the time, an issue, asking, Are these housing projects doing more harm than good?” In Gold’s mind, “you really should write from the perspective of your knowledge,” and he and Ostrander knew a lot about the place. If Waller was going to be a hardened person, why not have her come from the hardest place in her creator’s home city?

Her précis complete, Waller made her debut in the first issue of a mini-series that was Ostrander’s DC debut, a 1986 crossover story called Legends. On page 15, we see a uniformed military man named Rick Flag go in for a meeting with someone he’s never met, a woman who runs something called Task Force X. Before we even see her face, the dialogue establishes her personality: “You’re Amanda Waller?” Flag asks. “You see anyone else in the room?” she shoots back. When she shows him her plans to build a team of coerced villains, he’s aghast, yelling, “Are you out of your cotton-picking mind, lady?”

Turn the page and you first see her face, modeled by artist John Byrne on actress Nell Carter. Wearing thick, purple eye shadow; boxy, black business wear; bunned hair; and a sneer, she brooks no bullshit. “Frankly, I couldn’t be more serious, colonel!” she shouts. “And by the way, if you ever again call anything about me ‘cotton-picking,’ mister — I’ll stuff those bright, shiny eagles on your shoulders so far up your butt, they’ll be able to nest in your skull!” Waller was already fully realized by her second page.

A few issues later, readers met the reluctant foot soldiers of Task Force X — informally known as the Suicide Squad — who were directed by Waller and corraled in the field by Flag. Right after Legends was over, they spun out into their own series, Suicide Squad, initially penciled by artist Luke McDonnell. It was a paradigm-shifting period at DC: The company had in the past three years destroyed and rebuilt its entire cosmology in a mega-crossover called Crisis on Infinite Earths, reinvented Batman in Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, and deconstructed the very concept of the superhero in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen. Suicide Squad, though less well-known than those three series, was still quite ambitious in its attempts to make mainstream comics appealing for grown-ups. It killed off characters, it had a cast of jerks and misanthropes, and its story lines were set in decidedly un-kid-friendly geopolitical hotspots like drug-war-ridden Colombia, Sandinista-controlled Nicaragua, and the headquarters of a group of Islamic militants.

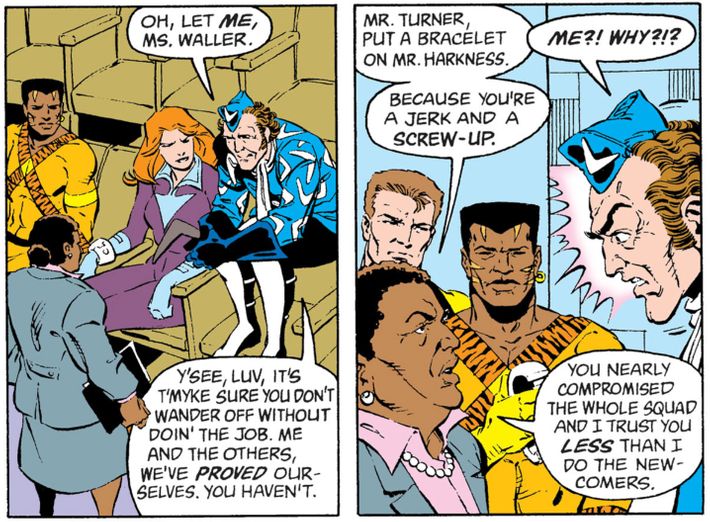

Throughout, Waller got all the best lines. In an early story, she has a meeting with President Reagan and repeatedly takes jabs at him. While describing her previous life, in which she was raising a family in Cabrini–Green, she remarks, “Of course, in those days we had some social programs to fall back on. You do remember social programs, don’t you, Mr. President?” Flip open almost any issue at random and you’ll find barbed zingers and scowling threats. “If I wanted commentary, I’d get George Will,” she snaps at the Penguin. When Poison Ivy puts a man under her spell, Waller twists her eyes at at her and says, “You’re a slaveholder, deep down. So make your boytoy here take a nap and let’s get on with business.” She calls dangerous criminals Deadshot and Captain Boomerang “Deadhead” and “Boomerbutt” just to get under their skin.

In one particularly memorable issue, Batman infiltrates the Squad’s headquarters and Waller is wholly unimpressed by him. “I promise you that, if you blow the whistle on us, I will find out who you are and do the same by you,” she says, extending an accusatory finger at the most intimidating hero in the DC universe. Indeed, her demeanor with everyone was cold-blooded. She attached bracelets to her team members, ones that would blow their arms off if they got out of line. She didn’t care if they died on a mission and was very open with them about it. In her every appearance — many of them co-written by Ostrander’s newlywed wife, Kim Yale — she was an action-movie delight, vivid and sonorous. She wasn’t a sex object, she wasn’t a role model, and she wasn’t a stereotype; she was something new and original.

“We got a lot of mail,” Gold says, and neither he nor Greenberger recall any of it being racist or misogynist. Readers glommed on to the book and often reserved special praise for Waller. Suicide Squad ended up lasting for 66 issues, a remarkable amount of time for an idiosyncratic book about lower-profile characters. In 1992, facing declining sales, it was canceled. However, Waller lived on: In the ensuing decades, she became an integral piece of intellectual property for DC, operating morally questionable teams and serving as a vicious bulldog for the government. She popped up in spinoff media, perhaps most notably as a sympathetic antagonist on the acclaimed Justice League Unlimited.

But when she made her big-screen debut, the character started to lose some of the characteristics that had long defined her. In 2011’s Ryan Reynolds–led bomb Green Lantern, she was played by Angela Bassett, and although the actress did a fine job bringing her to life, she had one major, controversial difference from her comics counterpart: She was svelte. That same year, DC Comics rebooted its entire superhero line, with reimagined and younger versions of characters appearing in series after series. One of the rebooted titles was a new take on Suicide Squad, penned by Adam Glass and penciled by Federico Dallocchio and Ransom Getty. Dallocchio recalls a very specific editorial edict: “Show her as the opposite of the Amanda from the old comic: thin and young.”

Sure enough, this new Waller was slender and youthful, a standard-issue female figure for the superhero genre. DC co-publisher Jim Lee says it was done largely as a way to tie in to Green Lantern. No matter the motives, the move was met with an immediate outcry from fans.

“That was a colossal mistake and it revealed their lack of understanding of the cultures that they were portraying with their characters,” says Joseph Illidge, a comics columnist who often writes about racial issues in the industry. In his mind, it was “speaking to the community that character formally represented and saying, ‘You are unattractive. You are not appealing. You do not have the same value in society. You, as a big, black woman, you’re not attractive.’” Ostrander declines to comment, but Greenberger is not so reticent, saying the changes “made her some other Amanda that I don’t recognize.”

Fortunately, David Ayer wasn’t interested in that new tack. DC parent company Warner Bros. signed the writer/director on to helm a big-screen adaptation of Suicide Squad in 2014, and although he says he read the rebooted series and took inspiration from it, he saw the new Amanda and had no interest in her. “I didn’t wanna do that,” he says. “I wanted someone who’s had a life and has a personal history and feels like they have the wisdom to back their play.” He was taken by her boundary-breaking depiction in the original Ostrander run: “This is the early ‘80s, and this is really a character study of an African-American woman. I feel like there’s a progressive quality about the comics.”

The result was the casting of Viola Davis, an actress who isn’t the size of the original Amanda, but is certainly much closer to her in age and look than the one that was running around the comics at the time she was cast. Davis seems to get exactly what made the character work when Ostrander crafted her 30 years ago. “I felt liberated to tap into that power,” she says, “with no vulnerability; to totally own it without apology.”

Sure enough, onscreen we see a Waller who closely resembles her envelope-pushing original incarnation, even if the depiction is a bit more extreme and unlikable than on the page: At one point she murders her FBI employees in cold blood, which is something Ostrander’s version probably wouldn’t do, and the device she attaches to Squad members blows off heads, not arms. (To be fair, that’s something the 2011 reboot version did, too.) Nevertheless, her core traits are still there: She stares down anyone who stands in her way, she’s willing to compromise any ethical standard in order to protect U.S. interests, and she has some solid verbal jabs: “Let’s just say I put them in a hole and threw away the hole,” she says of her team at one point, a line of dialogue that would’ve been right at home in her late-’80s exploits.

Davis’s casting and Waller’s new-old look has also had an effect on the world of comics: In April, without fanfare, she was abruptly changed in the comics to be older and larger again. And though the character has been written almost entirely by white men to date, a black woman, Vita Ayala, will be writing a few Suicide Squad stories starring Waller later this year.

In other words, there’s plenty of room for Waller to scheme and grow, and DC and Warners are placing her higher on their list of priorities than they ever have before. That’s no small accomplishment for a character who didn’t fit into any of the existing molds of success when a 30-something comics newbie dreamed her up three decades ago. “The fact that other people wanted to use her indicates that she’s been a really compelling character,” Ostrander says. “And, in that way, I feel that I’ve really done my job.”