The feminine voice that launches “Lonely Star,” the first song of the Weeknd’s second mixtape Thursday, seems foreign to the artist’s own. Gender’s only half the difference. Instead of singing, it’s speaking; its speech is delicate, high-pitched, needy, and eager to please, poetic in a conditional sense. Faint static and a piano that insists on a single chord accompany it. If, all I could say is if. Promise you won’t regret me like the tattoos on my skin. Light the wrong path. A heavily distorted low-pitched guitar begins to churn like a motor. Promise me when they all love you that you’ll remember me — when you fuck them, you’ll see my face. My body is yours, every Thursday. The piano cuts out as a bass drum commences a blunt, imbalanced, spaced-out rhythm to contrast with the rapid, steady oscillations of the guitar. Only then do the tones of Abel Tesfaye’s male falsetto ring out: It seems that pain and regret are your best friends. Cause everything you do leads to them.

In terms of sonic quality, the voice sounds the same as ever, but it’s clear that things have changed in another sense. When the Weeknd’s first mixtape House of Balloons emerged out of digital obscurity, in March 2011, virtually nothing was known of the act beyond the collection itself. At first it was unclear whether the Weeknd stood for a collective or an individual artist; in either case the real names and lives of the performer, or performers, was all but inaccessible. The only things the mixtape’s listeners could confirm were the gender of the vocalist and the excellence of the project as a whole. With its production’s flawless, stylish fusion of R&B and indie rock and electronica, its innovative project-length narrative, its frank approach to drug abuse, sexual license, and heartbreak, and the sheer intoxicating beauty of its singer’s voice, House of Balloons was instantly and justly regarded as a classic. To this day, in the wake of two further mixtapes and two studio albums from the Weeknd, House of Balloons is generally regarded as the artist’s best collection.

The curiosity regarding the artist’s “real identity” would inevitably be sated. It gradually leaked out that the Weeknd was Abel Tesfaye, a Toronto-area denizen of Ethiopian descent. Empowered by his own vocals and lyrics and backed by instrumentals from slightly known to unknown Canadian producers Doc McKinney, Carlo Montagnese, and Jeremy Rose, Tesfaye had created a groundbreaking, album-quality project while doing entry-level labor at American Apparel. Formerly reclusive, the artist began to play live shows to capacity crowds who knew his lyrics by heart; news and rumors about him crowded every music blog; Drake invited him to write for Take Care — in short, Tesfaye’s social status was beginning to rise to match his stature as an artist.

It’s no accident then that fame itself, as a theme, begins to feature more prominently in the Weeknd’s music following House of Balloons. Even on that mixtape Tesfaye was singing about women who wanted his potential as opposed to his love; still, Thursday marks his first sustained exploration of fame: its desiring and acquiring, its uses and abuses, and above all its disjunctions. New meanings demand new sounds. With its straightforward invitations to get romantically high in popular settings and get chemically lifted to smooth out festive anxieties, House of Balloons is a collection designed to sweep the listener away, and as such its sound is dominated by broad, seductive melodies, crisp, catchy, readily legible hooks, and narrative clarity: Confessions of lust and love are threaded through a linear timeline — there’s the invitation and the party, then the after-party and the aftermath.

Though Thursday, which turned 5 last Thursday, retains many of its predecessor’s narrative elements (the boy-meets-girl-over-drugs plot forms the spine of both mixtapes as well as that of Echoes of Silence, the mixtape released following Thursday), it does so only to warp them into novel arrangements. Tesfaye’s lyrics are harder to make out and his tone is harder to place; his language is neither direct nor opaque, but intermediate, diagonal. Narratives fracture, and characters are no longer as cleanly delineated from one another: Identities meld and clash, and the plotline tangles as a result. Smooth, extended melodies have been whittled into narrow riffs; meanwhile, subdued drums have given way to hard percussive blasts suggestive of disruption, even punishment. The driving bass and snares and the line about pain and regret being your best friends lead the way into a collection where the power and spirit of judgment are frequently invoked.

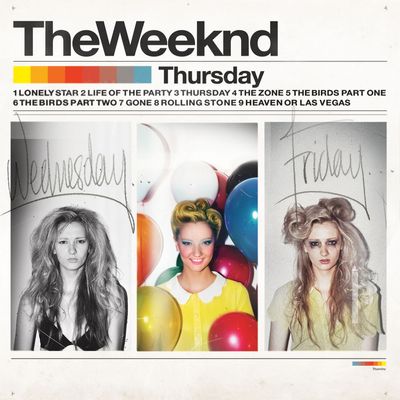

The ultimate origin of all this turbulence, though, lies in the greater emphasis laid on the female half of the romantic pairing at the mixtape’s core. The woman on the cover image of House of Balloons has her face entirely obscured by a balloon, and the lighting of the black-and-white photograph precludes any certainty regarding her skin color; her anonymity matches the generic, universal nature of the “you” Tesfaye addresses throughout the mixtape. What female voices exist on that mixtape exist only in the distance, as sampled tracks: Aaliyah, Siouxsie Sioux, the Cocteau Twins’ Elizabeth Fraser. There’s no possibility of the beloved speaking up. The cover of Thursday, on the other hand, features a triptych of images of the same woman on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. In each photograph her face is wholly visible: Just as she wears different clothes and makeup in each, her facial expressions on each day are distinct from one another.

The gain in variety and detail is reflected within the mixtape, where her voice appears on two tracks and her actions drive the plot at least as much as those of the narrator/protagonist played by Tesfaye. However desperate the female lover becomes over the course of the story, she retains her sense of agency. None of this is to claim that Thursday is a feminist work of art, or even suggest that any equality is possible between its lovers. The female lead of Thursday begins in need and ends in despair; her male counterpart almost always holds the upper hand. But his moments of fragility offer the occasion for a revision of the story that inverts its initial assumptions: Tesfaye’s commitment to thematic subtlety and symbolic complexity means there’s more to Thursday than any single reading can contain.

One reading of the story of Thursday runs roughly as such. A young man encounters an emotionally fragile young woman. He seduces her with the promise of fame and the aid of drugs; she needs him more than he wants her. The sexual arrangement that ensues is both imbalanced and unconventional. He will sleep with her only on Thursday (“I love her / Today”); from Friday to Wednesday he’s open to pursue other affairs (“I’ll be making love to her through you, so let me keep my eyes closed”). But the girl’s emotional attachment grows. She begins to call him on days other than the fifth day of the week. The narrator finds himself surprised, and then worried. His past experience of deprivation has instilled in him a numb mentality, yet the eagerness of girl Thursday threatens to thaw out his persona and render him equally enamored, and vulnerable.

And I’mma lean

(“The Zone”)

Till I fall

And I don’t give a damn

I’ve felt the ground before

I left it all behind

I didn’t need no one

But I’m in heat tonight, baby

I’ve been alone for too long.

“Don’t make me make you fall in love,” he warns her on “The Birds (Part 1)” over an unremitting martial drumbeat, but of course by then it’s too late. On the sixth track, “The Birds (Part 2),” overcome with jealousy and despair, she feeds him an overdose of drugs and kills herself in front of him with a gun. The remaining three tracks of the nine-track project serve as a sort of prolonged coda: On the sprawling freestyle “Gone” and the pensive “Rolling Stone” the singer resumes his customary bacchanalia while on the final track “Heaven or Las Vegas” he declares himself God.

It’s a puzzling finish, in many ways, particularly when one considers that the artist himself has been clear that the whole of Thursday was conceived as a concept album. It doesn’t add up: Boy meets girl, girl kills self and kills boy with drugs, boy ingests more drugs and announces his godhood? It’s possible that the protagonist survives his dosing and moves on without further consequences, but given the shock and horror in his voice as he watches her die, it seems unrealistically callous even for him. It makes for a sloppy, lopsided story if the girl at the center of the narrative exits it completely two-thirds of the way through without the slightest memory or mention afterward. If Thursday were a narrative conducted in written words, a novel or novella, one could swiftly write it off — too operatic, not enough logic or nuance. But music can withstand levels of melodrama, contradiction, and vagueness that would kill a story dead; it’s a testament to Tesfaye’s intelligence and subtlety that he manages to impart the musical narrative of Thursday with such dense symbolism without ever succumbing to portentousness. Though the narrative takes fatal excess as one of its themes, the means by which those themes are elaborated are relatively compact and discreet.

Everything hinges on the girl who saves herself for Thursday, or more precisely her skin color. As mentioned, the young woman on the cover of House of Balloons was racially ambiguous — only the pale balloon obscuring her face suggested anything regarding her skin color, and that only weakly. But the woman on the cover and at the heart of Thursday is explicitly, unequivocally white. Tesfaye didn’t invent the highly charged symbolism where “white girl” stands in for cocaine, but his lyrics demonstrate an intimate acquaintance with the Southern trap music where the metaphor originated as well as an intimate acquaintance with hard drug use. Likewise, he didn’t create the Western world whose economy, society, and culture dictate that a singer can attain superstar levels of fame only by appealing to a white female audience, but he lives in that world and has to make his fortune within it. It doesn’t take long — just the first two tracks — for the mistress in Thursday to become its master metaphor: She’s linked to the prospect of fame on “Lonely Star” and to the usage of hard drugs on “Life of the Party.” So the reclusive artist’s ambivalence toward fame, dependence on drugs, and racialized sexual desire are fused together and focused onto a single, increasingly troubled figure. If the macabre outcome of their relationship represents his foreboding that the pursuit of fame/drugs/white women he’s being drawn into will result in death (whether symbolic, real, or both), the final three songs, with their intimations of afterlife or near-death, suggest that that he’ll have to commit himself fully to that pursuit regardless.

Yet even this fails to exhaust the symbolic potential of the central figure. One of the stranger features of the mixtape’s closing third is its uncommonly gentle, even grateful tone regarding “you”: on both “Gone” and “Rolling Stone” he tenderly repeats the phrase I’ve got you while on “Heaven or Las Vegas” he exults, I never prayed a moment in my life / Girl I’m rewarded with you / I’ve been rewarded with you. If Thursday’s mistress has already passed, then who is “you”? What if it isn’t just a white girl, or drugs, or fame, but the one thing that enables the artist access to any of those, namely his voice? In an interview last year promoting the release of his album Beauty Behind the Madness, Tesfaye revealed that the female voice whose speech commences “Lonely Star” and Thursday is actually his own pitch-shifted voice. In that interview, as in others, Tesfaye’s words evince a modesty and humility that stands in sharp contrast to the self-vaunting in his music: House of Balloons concludes with a declaration of his omniscience just as Thursday concludes with a declaration of his godhood. It’s not hard to see how, given Tesfaye’s shy temperament and history of deprivation (raised in relative poverty by his mother and grandmother, he dropped out of high school, abandoned his family, and for years lived criminally and on the verge of homelessness), his own voice, in its unreal elevation, effortless richness, and alienating purity, could seem to him a being separate from himself, a gift he never could have merited, a god. Given that the mark of a god is its power, and given how, as predicted on “Lonely Star,” the power of his voice has carried him from dire poverty to boundless abundance, it’s hard to argue against such belief.

The typical criticism of Tesfaye has always been that he’s too solipsistic, and it’s not entirely groundless: One of his deepest themes is that of the love affair that individuals conduct with their own isolation. But solipsism, in its inscrutability and lack of conscience, makes for an aesthetic far more banal and irrelevant than the aesthetic on display in Thursday, which translates the singer’s longings and loyalties into an accessible, precise, and complexly rewarding discourse. House of Balloons is a masterpiece: cool, sleek, and gorgeous, it’s the Weeknd project almost everyone (myself included) is likeliest to put on. But Thursday deserves a praise all its own: With its heavier social tensions, rougher charms, and more distorted beauties, it’s the collection of Tesfaye’s that’s most uniquely essential, and powerfully charged.