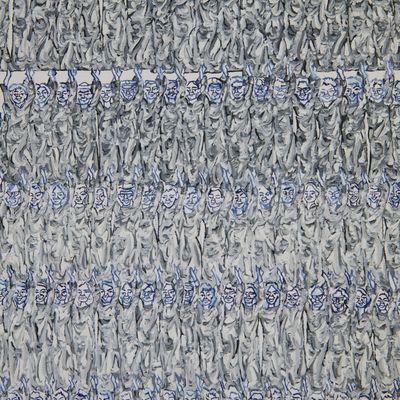

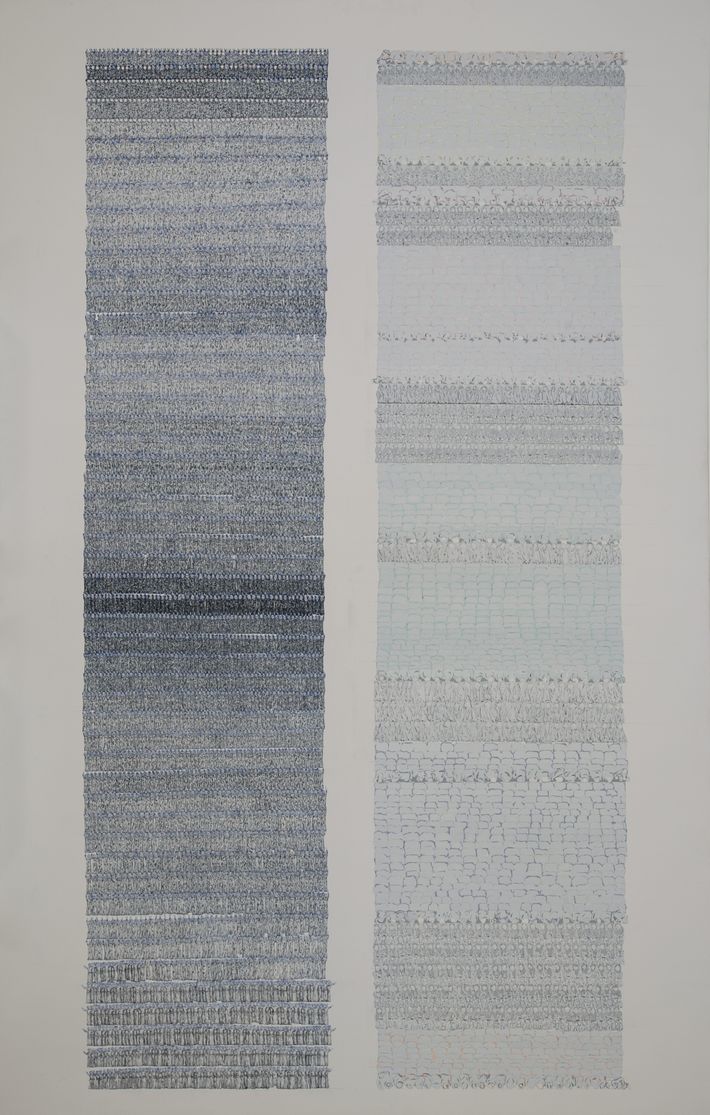

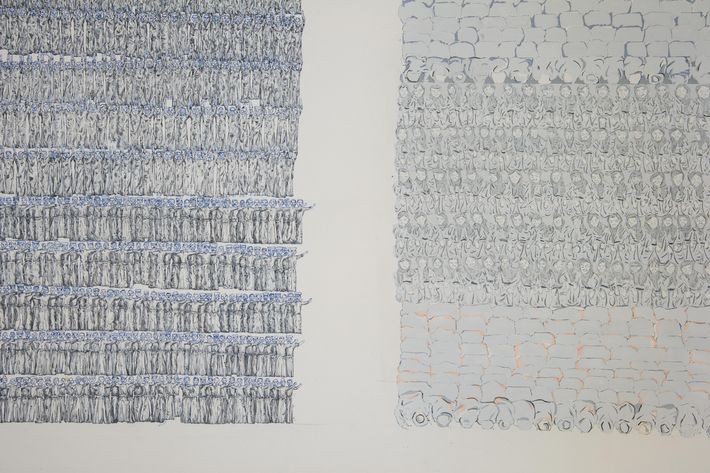

Fifteen years ago, the artist Schandra Singh was living just south of the World Trade Center. She lost almost everything she owned on September 11 ÔÇö her apartment was blanketed in drifts of toxic soot ÔÇö┬áand very nearly her life. And then she made this painting, on a canvas that she found still sitting on an easel in her apartment afterwards. She painstakingly depicted every person who died on that day, individually ÔÇö recognizably┬áÔÇö┬áon the left. Most of them are smiling, their arms raised, carefully grouped with the family members they died with that day, some holding their children. And then, on the right, more equivocally, it depicts people in traditional Muslim dress, praying.

She did it as therapy, or exorcism, or tribute. It took her a year. It has an obsessive, devotional mutedness, which is very different from the vibrantly demented portraits of people she met on vacation sheÔÇÖs become known for. (More recently, sheÔÇÖs started painting Revolutionary War reenactors.)

Singh was born in 1977. Her father is Sikh and survived the horrific partition between Pakistan and India. Before her parents married, her mother, who is Austrian, had traveled the world teaching at American Embassy schools. Singh attended RISD, and much of her art is inspired in part by the effects of globalism. In 2000, she spent a year living in a village of Muslim farmers by the Black Sea in Turkey.

Today the painting, propped up on two plastic file boxes, leans against a wall in her studio, on the top floor of an old commercial building in Poughkeepsie. Over the years, it has attracted the interest of various collectors ÔÇö Alec Baldwin even approached her once ÔÇö but she was never interested in selling it.

Earlier this year, curators at the The National September 11 Memorial & Museum heard about it. They sent delegations up to see it, although it was too late to include it in its show Rendering the Unthinkable, which opens September 12.

ÔÇ£It came to our attention through a [victimÔÇÖs family member,]ÔÇØ says Jan Ramirez, the museumÔÇÖs chief curator. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs just an extraordinary work, itÔÇÖs kind of exactly the sort of piece which merits collection and preservation in our collection.ÔÇØ (Although, she admits, they have been ÔÇ£cautious about art in part because there is a significant storage cost.ÔÇØ)

This is the story of SinghÔÇÖs escape that morning, what it meant to make the painting at the time, and what else it might mean today.

The 9/11 museum curators were here recently. What was that like?

They did something that no oneÔÇÖs ever done before with this painting, which shocked me: They just started naming the people. IÔÇÖve lived with this for years now, but these people are less than a half of an inch big, their face, not even. So the very fact that theyÔÇÖre that small and they could tell me who they were was kind of amazing. ItÔÇÖs when I remember the magic and the craziness of the painting.

I did this painting in 2002 and 2003, and I actually gathered every image of every single person who died and I had their biographies.

When you first look at it, it seems like a pattern in gray scale.

Then you get closer and you realize itÔÇÖs people. Then you get even closer and you realize itÔÇÖs all individual people. In many ways, that was very much what September 11 was. We were all watching these towers burning, but nobody could see what was inside. This is what was inside. So thatÔÇÖs an explanation of the painting.

Tell me about what happened to you on 9/11.

I was living on Greenwich Street and Rector, between Albany and Liberty. I was a block and a half or two blocks from tower two. I never wanted to paint the World Trade Towers. They were just never anything I was interested in. They were actually always in my way. To get uptown, I had to go through them because I was so close to them.

I remember my roommate had just moved out, and I had enough money to have the apartment for myself. A friend had sent me a piece of art. I put it on the wall. It felt like IÔÇÖm claiming my place in New York now.

That morning, I woke up at 7 or something, and I had these four eight-foot windows, but one was divided, and I made a room where one was, and I had a big thing hanging over it, but there was a crack where I could see the sky. There was an incredibly beautiful blue sky. I thought to myself, itÔÇÖs going to be a really beautiful day. I fell back asleep.

Then around 8:30 my phone starts to ring and the person will not leave a message. They just keep hanging up and hanging up. IÔÇÖm laying in bed ÔÇö who is calling me and hanging up?

Your landline because this is 2001.

I didnÔÇÖt have a cell phone. The cell-phone number I have to this day was got by my father on September 12. I get up to get out of bed and it was all overcast and I thought, wow, the day changed so quickly. I walked to the kitchen and I pick up the phone and itÔÇÖs my mother. She says, ÔÇ£Schandra, the World Trade Tower is on fire.ÔÇØ

So then I turned around and I finally looked at those huge windows I had and just things like a science-fiction movie ÔÇö things were just flying down, like pens and papers and peopleÔÇÖs things, like rain, were just coming down.

All the debris from the first plane, but it wasnÔÇÖt big stuff. It was little stuff flying down. I couldnÔÇÖt really look at what was happening. Also, I lived next to tower two, not tower one. Tower one was hit first. I was kind of calm. I decided to go to Battery Park, because I was so close to the World Trade Towers that Battery Park was the only place I could go without having to go into the World Trade Towers. I didnÔÇÖt know what was going on. I wasnÔÇÖt that scared. I had no clue. There were just things flying all over the street. I took my keys and a t-shirt. ThatÔÇÖs all I took out of my apartment. I was walking down my stairs, and then right when I was coming out of my building, there was this noise. I will never forget the noise. My building started to shake, and there was this incredibly loud noise. It was almost like something was cracking, but in a way youÔÇÖve never heard before. That was the second plane hitting tower two right next to my building.

So my whole building just shook. There was a gym there. The glass broke in the gym and I put my hands up in the air and I just went outside. I saw this huge fireball. I thought it was a bomb. Who would think it was a plane? I have to say that noise ÔÇö especially after I knew what it was ÔÇö was horrible. So then I was standing there, and very interestingly everyone was just standing there. People werenÔÇÖt talking to each other ÔÇö just staring up at the sky almost in shock. There was a mall underneath the World Trade Towers, and they started to evacuate people from the mall.

I remember this other woman came out: She was very overweight, and she was carrying all these bags. She was screaming out of her mind. She was screaming, ÔÇ£Oh my God. Oh my God. The families. Oh my God. The people inside. The families.ÔÇØ She was losing it. In many ways, I have a lot of respect for her because she was being very real at that moment. I went over to her and held her. I just was saying I know. I know. I was trying to calm her down.

After she stopped screaming, I backed away a little bit. Then all of a sudden my neighbor David tapped me on the shoulder. My relationship with David was, like, he was very handsome, lived down the hall. He would play soccer in the park and IÔÇÖd play tennis and heÔÇÖd wave. ThatÔÇÖs how I knew David. We gave each other a hug, and then we were just staring at it. We didnÔÇÖt really speak.

The falling debris was getting bigger. We were watching the debris and, all of a sudden, things just started to fall not like the debris.

People.

Debris would catch the wind, but the people wouldnÔÇÖt catch the wind. They would just drop. We were watching it, and we both were really quiet. I remember one man very well. I remember his suit. Then all of a sudden, pretty soon after we watched the people falling, tower two, which is the one we were right under, started to come down.

Did you think you were dead?

My first thought, which I thought might have been my last thought, was oh my God, IÔÇÖm dead. It happened so quickly.

So I remember thinking, IÔÇÖm dead, but then I grabbed DavidÔÇÖs hand and said we have to run. Because it imploded and it didnÔÇÖt just collapse or tilt over, [people] didnÔÇÖt just run right away. So we actually kind of got ahead of people with our running, and we ran all the way to the end of Battery Park.

I turned to David, and I was like, oh my God, weÔÇÖre alive. WeÔÇÖre alive. He remembered, when I was saying this, the big white cloud just taking me over. It was probably taking him over, but he was staring at me and I just turned white. So heÔÇÖs hearing me tell him IÔÇÖm alive, but heÔÇÖs also seeing me transform into a sculpture. Then it became really crazy because all of the sudden this cloud of white stuff was everywhere. People were running around, and I couldnÔÇÖt see 10 feet away from me. Our eyes were burning. Our throats were burning. It feels like you landed in outer space, but outer space felt like hell. ThatÔÇÖs what it felt like.

In front of us was this wooden pier. There was a 10-foot barbed-wire fence blocking it. I said to David, thatÔÇÖs the farthest we can go without having to actually get in the water. He started climbing the fence. He ended up cutting up his stomach, which we didnÔÇÖt realize until three hours later because we were so hyped up. I got stuck on the barbed wiring. He came back and got me. So we get on to this pier, and there are seven men and IÔÇÖm the only woman on the pier. There was a construction worker, there was a Mexican dishwasher. There was this guy from the Deutsche Bank who was sitting there the whole time on the phone in his suit. Everyone he knows is dead. There were a couple of other Wall Street guys. The construction guy was pacing back and forth, saying, ÔÇ£When I get out of this, IÔÇÖm going to get a gun and IÔÇÖm going to get my wife and child and IÔÇÖm going to move to the woods.ÔÇØ The Mexican dishwasher was petrified.

Then we hear this really loud rumble. Everybody knew what it was, knew the next tower had just collapsed.

It was like every man for himself. Some of the men decided to get in the water and start swimming. A police boat saw them and turned around to come get us.

What was interesting was the moment the boat came to get us all, the men said let the woman on first. It was like we became human, we became real. Once you thought you were okay, you were able to be a dignified person, which was really fascinating.

The sense of being human. So then we all got onto the boat, and then as the boat is going away, this woman comes out of nowhere. I donÔÇÖt know if she climbed the barbed wiring. I donÔÇÖt know how she got there. She was wearing a black dress. She was tall. She was screaming,┬áYou canÔÇÖt leave me here. DonÔÇÖt leave me here. Please donÔÇÖt leave me here. We turned the boat around, and we get her. She gets onto the boat, and as the boat is leaving, she falls over and has a heart attack. The policemen are trying to help her as we leave. I looked back, and I saw all the people trapped on Battery Park and that second wave of brown cloud just take them all over. That was a vision I will never forget.

WhereÔÇÖd they take you?

We ended up in Jersey City. This was the one comedic moment, if you could have any comedic moment in the escape from the worst terrorist incident in world history. We were walking across this parking lot and these two women are walking toward us. David said, ÔÇÿDo you know if thereÔÇÖs a place where we could go get some food?ÔÇÖ The women are like, if you go down that street, thereÔÇÖs a grocery store over there. They looked at us, and they said those are very dangerous streets. You may not want to walk down those streets.

And then we were walking in a park there, and these jets flew above us. I got scared. I said, oh my God, whatÔÇÖs going to happen now? I said, this is like war now. TheyÔÇÖre going to start dropping bombs on us. Then David said, ÔÇÿNo, donÔÇÖt worry. Those are our guys.ÔÇÖ He goes, ÔÇÿTheyÔÇÖre probably going to get whoever did this to us.ÔÇÖ Then at that moment, instead of feeling safe, I instantly thought of how I had lived with Muslim farmers before. I knew that they were people like us just trying to survive. They were moms and dads and little kids. They adopted me into their family.

I knew that now with our form of going to get them, they were going to now feel what I just felt, or maybe not even have a chance to feel it and maybe just die. I didnÔÇÖt want anybody to feel like they were never going to see their family again, or to think that they were going to die. Instantly, I kind of said a prayer for them. In my brain I closed my eyes and said please, just because of the craziness of a few, now a thousand other innocent people are going to die.

Tell me about deciding to make the painting.

So the canvas was there and it was kind of calling for me to do ÔÇö something. I remember it was a cold, rainy November day. I was walking, staring right down at Ground Zero, walking to my building, and I just kind of saw it in my brain. I think thatÔÇÖs the way artists sometimes work, too. ItÔÇÖs just magic. It just comes.

Then I also thought to myself, this is a totally crazy idea. I thought I want to paint everybody who died, but then I also said I want to paint Muslims on one side and everyone who died on the left side. I want to do it on that canvas that survived the disaster, but then I also thought, in my brain,┬áthis is a totally crazy idea. Then I ended up moving to L.A. because I lost a lot of things and my job. I couldnÔÇÖt make any art. I didnÔÇÖt want to make anything that was going to be critiqued. I didnÔÇÖt want to make anything that was going to be about art or the art world or art this or art that.

And so you decided to do this crazy idea.

And I started gathering all of the images every day of every person. So IÔÇÖd sit on the computer and go through this site called Legacy and print out everything, everybody.

And you moved back to your familyÔÇÖs house in Vermont to make it?

My parents let me, as long as I agreed to apply for graduate school.

How long did it take you to paint it?

I really thought it was only going to take me the fall, but it took me a year to do. I wouldnÔÇÖt allow anybody to see it. I needed to do [it], and I didnÔÇÖt want to know what anybody else had to say.

In a sense, every day I had to go into a room with 3,000 people who died. I had smelled these people. I was there. It wasnÔÇÖt that it wasnÔÇÖt easy. It was as if I remember the anniversary of September 11 that year. I really didnÔÇÖt like it, and it was because I almost had to psych myself out and believe they werenÔÇÖt dead. If you look at the painting, all the people on the left side are smiling because it was the images that the families put out. For me, it wasnÔÇÖt about death. It was about bringing them back to life. I had to live with them in my brain having to be alive.

I had people telling me I was crazy. I needed to get off the mountain, and what was I doing going into this room every day with dead people. It didnt  it was not a rational thing to people, what I was doing. It was my therapy too. They talk about survivors guilt or whatever. I dont know if thats why I did this painting, but this painting was my way of going in and doing something.

Then I did it, and nobody had seen it. When it was done, I called my mother because we needed to move it. So she comes up with the van. This is the first time sheÔÇÖs seen what IÔÇÖve been doing. No idea what IÔÇÖve been doing up there for a year. She looks at the painting. She doesnÔÇÖt say anything. She just looks at it. She walks out. She pours herself a glass of wine.

So this was the painting you said you used to apply to Yale.

Yeah. So this painting and a couple of other works on paper. Actually, they challenged me on this painting in the interview.

In what way?

I was shocked. But he was just testing me. In the interview, he said, ÔÇÿI could look at this painting and walk by and not care about it. How would you feel if I didnÔÇÖt care about this painting?ÔÇØ I said, you could just walk by this painting and not care and not see it. ThatÔÇÖs fine. You could walk by this painting and know somebody who died in it and want to see if you could find them or see if itÔÇÖs possible to see if theyÔÇÖre in the painting. Or you can look at this painting and you can think that the level of intensity and insanity of what I just did is equivalent to the insanity and intensity of that day. He said, ÔÇÿOkay.ÔÇÖ

But a lot of times, I just live with it. I make my other paintings and go on to do whatever IÔÇÖm doing. But then once in a while, someone asks me to find somebody. So then I go looking for them, and I go look at the painting. When that happens, IÔÇÖm like,┬áhow the hell did I do this? Then it hits me. Then IÔÇÖm like,┬áwhat the fuck, this is crazy. I donÔÇÖt think of it as crazy, but when I have to go do that ÔÇö find a person ÔÇö IÔÇÖm like,┬áwhoa.

Why didnÔÇÖt you ever sell it?

I never wanted it to go into a private collection or have the wrong person controlling it. ItÔÇÖs meant to be seen by people. ItÔÇÖs a relic in a weird way, too.

So you wouldnÔÇÖt want to donate it without some guarantee of it being kept on display?

It wonÔÇÖt be hard for me to let it go if itÔÇÖs being seen. WhatÔÇÖs happening in our world right now with this whole anti-Muslim rhetoric and this whole 9/11 being used in certain ways and the recent surges of terrorism in Western countries, I feel like the painting has a new voice, and the voice should come out now, too. It had a voice right after September 11. It will always have a voice, but right now, it could speak again in a new way.

I think someone at the Memorial Museum said to me, ÔÇÿIs this a political painting?ÔÇÖ I said, this isnÔÇÖt a political painting. This is a human painting. This is about humanity.

I painted the Muslim side because I wanted to not make a memorial. I wanted to ask a question with the painting for everybody. I wanted everybody to have their own idea of what they think the Muslim side is.

How do you think it might fit with the story that the 9/11 Museum now tells?

They have the shirt of the guy who killed Osama Bin Laden  its one of the last things you see when you leave the museum  Id love to see my painting paired with that because we shouldnt leave with retribution. We should leave with understanding. So there should be a way to create understanding. So in a sense, it bothered me, the shirt, a lot, but then in a weird way, I was like, the painting needs to go there more because its like it should counter that. We need to counter that.