After the dizzying and astonishing trek through episode one, “When the Battle Is Over” lands us back in familiar Transparent territory. And let me be the first to say: It’s a relief to see Shelly and the Pfefferman kids again.

Maura’s one-woman quest through South Los Angeles was remarkable and absorbing, but her story always finds Transparent at its most unreservedly sincere. I’m not going to argue that the show should be funnier — calling it a comedy is an incomplete label, at best — but it can be heavy and self-serious, meaning it’s best served when it plays with a few different tonal registers. It benefits from being told through many voices. And even though the Pfeffermans’ voices are often the worst, they are often also the show’s most successful storytelling devices.

But boy, are those Pfeffermans pretty much the worst. After her traumatizing collapse in the Slauson swap meet, Maura’s stuck in County hospital, where her name on the patient board is spelled “Feffman” and her sex has been circled as “M.” Even worse, the first person who comes to help her is her sister Bryna, because the only phone number Maura could remember was the one from her childhood home. True to form, Bryna is initially sympathetic and then quickly disgusted when Maura asks her to change the sex on the patient board.

When they arrive, the kids are no better. They’re freaked out by the hospital atmosphere, and squeamish about the other patients. Although they put up a good show for the doctor, trying to insist that he call Maura “she,” each of them bails as quickly as possible when Vicki arrives to take care of everything. Later, back at home with Davina, Maura admits that she’s long avoided paying any attention to her body, and it’s probably time to change that.

This setup kicks off a familiar Transparent structure, which follows each of the Pfeffermans through their own little stories. We learn that Josh has launched his own music label, and it’s the sort of place where you have meetings in something that looks like a giant, elaborately carved, cardboard toilet paper tube. We also learn that Josh is still deeply unhappy — his doom only lifts after Ali shows up at his place and he makes her dinner.

The Pfefferman sisters are each happier, though also unsettled. Ali’s deep into her graduate career, enjoying life as a T.A. and enjoying surreptitious make-out sessions with Leslie after class. However, the strain of that relationship is immediately apparent: In an after-class grading session with some other students, Ali listens while they describe Leslie’s penchant for adopting a new grad-student lover from each class. Even more troubling is how, almost mid-kiss, Leslie scolds Ali for teaching material slightly outside the class’s brief.

That said, Ali has unquestionably evolved since season one. She looks legitimately happy to be teaching her section, and she seems thrilled to talk about complicated ideas of race and white fragility with her peers. Given the short bit we see of her class, she seems really committed to her work on historical memory. Of course, we also get several snippets of the Ali we knew from the beginning. She’s defensive when pressured into considering her whiteness. She has no idea how to respond to her classmate’s sexual experimentation with Leslie’s testosterone cream. The hilarious peak of her immaturity is when she describes the rigors of being an Airbnb host to Josh. You have to wash the sheets and the towels every time. These people, she tells him, are Nazis! Oh, Ali.

(Sidebar: The scene in the grad-student lounge is classic Transparent, yet another chance for the show to winkingly introduce complex ideas about identity. These scenes almost always work on two levels: There’s a bit of a chuckle over the trappings and pomposity of academic language and ideas, and there’s a small, earnest streak of didacticism. If you hadn’t really thought about “white fragility” before, Transparent wants you to maybe just interrogate that idea a little bit.)

So Josh is unendingly sad, and Ali sees storm clouds on the horizon. That leaves Sarah, Shelly, and Raquel, who are all tied into a loosely related temple story. Raquel is helping Sarah become a member of the temple’s board, and also welcoming their new cantor (who, as she quickly points out, looks like an interesting match for Raquel). Sarah’s quest for board membership leads to some impressively inappropriate nervous babbling about her sexual orientation, her thoughts for the future of the temple, and, somehow, her ex-husband’s millennial girlfriend who has been ruined by the internet and is now ready to suck cock all day. In fairness to Sarah, the subsequent scene with Len and his girlfriend does prove her point.

“When the Battle Is Over” strongly hints that this season will pick up some of the ideas that circled around Sarah in last season’s Yom Kippur episode. That episode featured her stunning inability to see past her own needs, and this one returns to that same point, especially as she’s being serviced by a halfhearted dom in an S&M club. By highlighting how Sarah’s understanding of giving is wrapped up in her need for congratulations, “When the Battle Is Over” suggests she might actually examine that issue down the line. That’s the big takeaway from Sarah here — along with the reveal that she’s once again living with Len — but even without those beats, the straight-as-an-arrow board members joking about how the phrase “LGBT” always makes them want a BLT would’ve been enough to justify this plot.

It is sad, but unsurprising, that most of the Pfefferman family is still wandering in search of themselves. Their longing for escape is written all over this episode: in Ali’s lecture to her students, in the lyrics of the song Ali and Josh remember from childhood (“we’ll run off together / to the sea”), in Sarah throwing herself into the temple as a new cause. And yet, as seen in the brief flashback during Ali and Josh’s sing-along, none of them knows whether they want to escape to the future or somehow slip back into the past. Think, for instance, of the childlike underwater tea party in last season’s finale, or Maura’s project to get her childhood photos altered so that her younger self looks more like a girl. Even at its most horrific, as in the Nazi sequences from season two, there’s something nostalgic about flashbacks on this show. It’s a wistfulness for lost time, even if that time is different in memory than it was in reality.

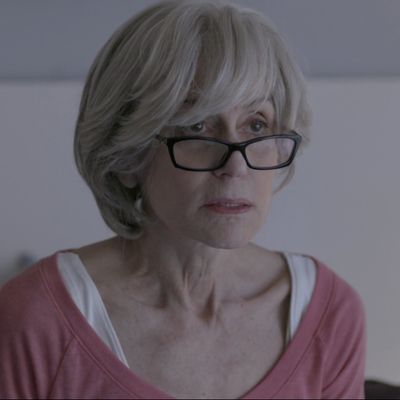

There is one Pfefferman who seems to have things figured out, though. Shelly, who has managed to grapple with the changes in her life so thoroughly that she can reduce them to several three-by-five index cards, is proudly coping with Maura’s transition by making it all about her. If there was ever any question of Judith Light’s greatness in this role, her reading of “To Shel and Back,” followed by her heartfelt, thrilled rendition of Diana Ross’s “Touch Me in the Morning” would put them to rest forever. There is a pretty long tradition of mocking one-man or one-woman shows on half-hour comedies. If Transparent follows suit, it will be very conventional but also very welcome.