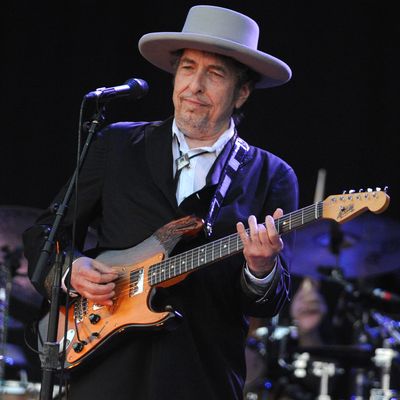

Because this year wasn’t weird enough, Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature this morning.

It wasn’t exactly a surprise, because some folks, this writer included, have been suggesting it for years. But it was shocking in that it had the force of recognition and resolution, and in the fact that, in the stolid terms of the Nobel, it is almost, if not quite, unprecedented.

That precedent as far as I can see rests with one person: the profanely comic and adroitly provocative Italian playwright Dario Fo, who died, sadly, just hours before Dylan’s prize was announced. The awarding of the Nobel to Fo in 1997 sent the Catholic Church, whom he targeted most brutally, into a paroxysm of rage. The one for Dylan, many years ago, might have had the same effect in many circles.

Dylan got it because he was one of the signal poets of the 20th century. He was a folk singer, a rock star, a provocateur, and, now and then, a crank. But more than anything else, before he even sang his words, he put them to paper, crafted them with an unappreciated care, and intended them to mean something.

You have heard of his influences: Woody Guthrie’s Commie Dust Bowl songs, to start, and then throw in the folk-blues. The Great American Songbook (which Dylan’s seemingly depthless memory seems to know completely). The Surrealists. The Beats. Later, some psychedelia, the Bible, and other stuff.

The result, while varied — ballads, screeds, epics, poesy, and of course classic after classic after classic — were of a whole. They were Dylan songs, and the words were Dylan poetry, and, again and again, the words, to quote the poet Bryan Adams, cut like a knife.

“Chimes of Freedom” may be among the greatest pieces of lyric poetry of our time. The heavens open, and thunder cracks, and lightning flashes, and the account of all of this is delivered in florid prose in the first half of each verse. (“In the wild cathedral evening the rain unraveled tales/ For the disrobed faceless forms of no position,” for example.) But in it all, Dylan hears something like an insistence on justice, and lurches suddenly, in the second half of each verse, into an almost hypnotically colloquial way of speaking to detail whom the lightning and thunder were recognizing.

It’s a list of the most fucked up and fucked over people in the world:

Tolling for the rebel, tolling for the rake

Tolling for the luckless, the abandoned an’ forsakened

Tolling for the outcast, burnin’ constantly at stake

or

For the mistreated, mateless mother, the mistitled prostitute

For the misdemeanor outlaw, chaineded an’ cheated by pursuit

This is a list I would almost call Biblical, were it for the fact that many of these folks are of course Biblical victims, but even there Dylan knows that religion is just one of the things that produces such suffering.

Poring over the song, the members of the academy would have found the words “for those compelled to drift, or else be kept from drifting.” It might have occurred to them that that Dylan had precisely limned two of the great tragedies of the 20th century — ethnic cleansing and forced exile, on the one hand, and the gulag on the other — in a single prosaic line.

Or how about this: “For the lonesome-hearted lovers with too personal a tale”; they might have seen at least a hint of recognition of the fights to come in the realm of interracial marriage and, of course, gay rights.

Moving on, they would have found fever dreams in “Visions of Johanna,” bleak Westerns in “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts.” They would have found a naked lover’s plea (“I can change I swear”); a barked dissection of capitalism (“money doesn’t talk, it swears”); a broken parable, as enigmatic as a Sapphic fragment ("There must be some way out of here, said the Joker to the Thief”); and lancing accounts of injustice that the word cinematic doesn’t do justice to ("The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” “Hurricane”).

The Swedish Academy also had some other things to think about. As the world changes and the fruits of our creativity becomes universal and available to all, they might have surmised that the notion of the “popular” has changed. Could they forever ignore it? Did they want Dylan, now 75, to pass away unrecognized? If that happened, how could they acknowledge any writer from the sphere of pop culture without the embarrassment of having not cited him?

And in fact, even if the notion of the popular caused suspicion, was it really true that Dylan the writer sought popularity? He came of age when the notions of what exactly a pop or rock star was were inchoate. Like his entire generation — encompassing both a Jewish kid in northern Minnesota and four working-class Liverpudlians — he saw Elvis with a shock of recognition. He certainly moved toward that flame. But quickly he saw the downsides of this (in the song “Desolation Row” most particularly), and almost as soon as his career began, moved to confound his audience, friends, and mentors. He went electric, yes, but then country, and then back to rock, and thence to ill-tempered Christianity, and on and on and on over the decades.

His journey has unfolded in front of us. He was a part of a generation that, like him, has aged gracefully in some ways, in other ways not, and his presence has been a part of each generation that followed. From this perspective can we see him clearly? Maybe this is what the academy is trying to tell us, or at least get us to think about. Can we see a Dante, a Homer, a Whitman, this close up? If we think about it, and argue about it, haven’t they made their point?