In a landscape of formal inventiveness, when the half-hour “comedy” feels increasingly like the place to strike out into new ways of telling stories and to welcome new voices, Netflix’s The Ranch is a bizarrely staid throwback. The streaming network’s platform means that its original programming could, hypothetically, bear very little resemblance to the TV that came before. There’s no need for episodic structure in the way we used to have it, there’s no need for live studio audiences or four-cam setups, and there’s certainly no need to stick to a storytelling form that was invented many decades ago. A streaming half-hour can be innovative, it can be risky, it can be an opportunity to be original and new.

Or it can look like The Ranch — which premiered the second half of its first season last Friday — a show that uses the Netflix creative carte blanche mostly as an excuse to dress up a very old structure with a little more swearing. The show looks like a brontosaurus in the age of mammals — slow-moving, not especially bright, and adapted to survive in a world that no longer exists. The premise is well-worn territory. Ashton Kutcher plays Colt, a football player who’s failed to make a professional career for himself, and has moved back home with his father and brother to help work on the family ranch. Family members living together under strained circumstances may be the hoariest sitcom premise around, and the kinds of jokes The Ranch mines from this setup are so familiar that I guarantee you are already capable of imagining them for yourself.

As you may have gathered, this is not going to be a glowing review of The Ranch. It is a comedy that is not especially funny, which is about the worst thing a comedy can be. But there are also some things that old structures and paradigms do pretty well, and some important fictional work that can get done with very timeworn stories. Some of those hackneyed ideas for how to make television can be good, and ditching them can lead to boggy, poorly paced narratives. Some of them are fundamentally useful tools for telling good stories (especially my beloved episodic form). And a story you think you already know, about a part of the country you may think deserves to be safely ignored, can still be worth telling. The Ranch is not very funny, but that doesn’t mean it’s not valuable.

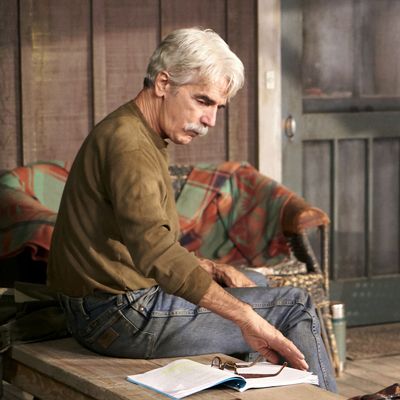

Colt and his brother Rooster (Danny Masterson) live with their father, Beau, who’s played with a charismatic, laconic aridity by Sam Elliot and his mustache. Debra Winger plays their mother, Maggie, who’s still married to their father but has moved out so that she can have her own space. Every single joke between Colt and Rooster is as inane and juvenile as you’d expect of a sitcom starring two That 70s Show alums, and it does not get better once Colt starts dating a young woman and Rooster starts dating that woman’s mother. But the series also spends quite a bit of time on the realities of running a ranch in Colorado, and the real financial hardships Beau’s trying to face. These are the moments where The Ranch ceases to be just a mediocre fictional throwback, and does something much more worthwhile.

In one episode, Beau has to make a decision about one of his calves, who’s probably sick with a bacterial infection. If he pays the vet for antibiotics, and they work, Beau’s out $250, and then he can sell the calf for about $1200. But the antibiotics may not work, in which case it dies, and Beau’s out the price of the calf and the price of the medicine. Or, the calf might get better on its own, no medicine needed. That episode, the seventh in the first season, is full of jokes about Colt’s struggle to break up with his girlfriend, and Beau’s stubbornness, and Rooster’s unimpressive mental facilities. But the calf story is played for wholehearted sincerity. Beau frets over it, trying to weigh the financial burden with his natural inclination to save an animal. (It helps that The Ranch uses a real calf in these scenes, and its fuzzy ears keep sticking out over the railing.) He sits up with it during the night. He tells it the plot of Shane. He pays for the antibiotics. The calf dies.

One episode later, Beau turns off the ranch’s electricity — he’s run out of money until he can put the cattle up for sale.

The Ranch may not be all that funny, but in its best moments, it’s a portrait of a family, of an American experience, and of a strained, unromanticized, often uncertain way of living. It presents that portrait in a package that’s digestible and familiar and accessible. It may not always succeed at what a comedy should be, but it’s in the vein of some of the best of what sitcoms have been. Roseanne, All in the Family, The Cosby Show, Murphy Brown — each of these, and lots of others, are depictions of protagonists and families who represented some version of “normal” that didn’t often show up on TV.

There are a few other shows on TV doing something similar right now. Black-ish is an often insanely hilarious series, hitting all of the familiar sitcom beats while also doing deep comedy dives into black culture and generational divides. The Carmichael Show is even closer to The Ranch in its deliberately Norman Lear structure, although it uses its characters less as people, and more as finger puppets with opposing viewpoints. Netflix’s animated series F Is for Family also has a few moments that approach The Ranch’s American realism, particularly as the father character tries to understand his kids. That show’s ability to speak to a modern norm, though, is hampered by its 1970s setting and a frustratingly Family Guy–esque sensibility. (Although I suppose this is another moment of overlap with The Ranch: They are both series that love to lean on testicular humor.)

The Ranch may not be for you. It is the kind of sitcom where a crotchety father holds up a carton of almond milk and demands that his sons “show [him] the tit on an almond.” It is a firmly Republican show, something that seems especially notable at a time when the entire country feels like it’s been divided up into Sharks and Jets, with nary a Tony or Maria in sight. There are no people of color on The Ranch. With the exception of Debra Winger, the women on the show are often uninteresting love objects. It is a show about pickup trucks and cows.

But in its own quiet way, The Ranch should be considered as a part of the same cohort of sitcoms that work to combine accessible, often dumb humor, with a careful, respectful, and compassionate view of an underrepresented American experience. It, and Black-ish, and The Carmichael Show, and most recently, ABC’s Speechless, are all coming at the same idea from different angles — how do we use a familiar structure to talk about uncomfortable, controversial, under-discussed things? How do we represent people with different lives as more human?

The Ranch is rarely as good as those shows, and it’s important to note that it starts from an easier place: Its subjects are white men. Of course Beau is a human to us; he is the default. But his economic strain, and his beliefs, and his vanishing way of life, still feel like a story that doesn’t often appear on TV. It’s a story worth telling.