Barring yet another not-quite-unforeseen catastrophe, the American presidential election of 2016 will come to an end tonight. But even now, in daylight, there’s already cause for celebration. Since the late-night time slot on Tuesday will be occupied by election coverage on the major networks, Monday night marked the final round of election commentary from late-night talk show hosts, a genre of discourse that, it’s safe to say, few will regret seeing go. Whether it’s mainstream liberals like John Oliver or Samantha Bee preaching to their choir or the path of least resistance taken by hosts like Jimmy Fallon, it’s clear that, as elsewhere in Establishment media, the political observations broadcast over airwaves in the wee hours have been helpless to make much sense (or laughter) of the lunacy activated by Donald Trump, whose candidacy exceeds any potential invective or caricature. The relative blandness and sobriety of the elections in 2008 or 2012 could be assimilated to the formatting of late-night television without much trouble, but when it comes to bringing audiences up to speed with a race (and racism) conducted at a frantic, unpredictable tempo, the hosts have nothing to fall back on.

Late-night shows are designed to soothe, mollify, and accommodate, but Trump’s jagged rhetoric of white nationalism has struck a chord precisely because he refuses all accommodation. Extreme reactionary politics have to be matched by equally extreme analysis and presentation, but extremism is antithetical to late-night television even more than it is to television in general. Though not always political (or not always traditionally political), only one late-night show has proven itself equal to the task of capturing the frantic, desperate tenor of this year’s politics: Adult Swim’s The Eric Andre Show, which recently completed its fourth season, and whose relentless, David Lynchian disruption of normality has taken on new resonance with 2016’s rebirth of explicit electoral pandemonium. Though the term has come somewhat unhinged in the process of repeated critical abuse, André’s show can still properly be described as “revolutionary.”

Since nothing revolutionary makes sense without a clear sense of what’s being revolted against, it makes sense to examine the presumptions and logic of late-night television, a genre mired in convention from its inception onward. There’s a strong case to be made that late night is the branch of television most resistant to change. Oldness trends conservative, and late shows are as old as television itself. As the tube completed its transition from an expensive contraption to affordable, omnipresent appliance in the ‘50s, NBC’s Tonight was already defining a place for itself in viewers’ barely waking lives.

In case you’re just joining us, this is Tonight and, uh, I can’t think of too much to tell you about it except I want to give you the bad news first. This program is going to go on forever. [audience laughter] Boy, you think you’re tired now, heh heh heh. [audience laughter] Wait till you see one o’clock rolling around …

Steve Allen’s introductory monologue, the first-ever for the program that would come to be known as The Tonight Show, was delivered in 1954, but virtually all of it could apply to late shows in the present: “It’s not a spectacular. It’s gonna kind of be a monotonous. [audience laughter].” Television as a whole is an extremely time-centered and time-sensitive medium, and since they go on later, longer, and for a less perceptive (because tired) audience, late shows while away the minutes far more than they excite the ear and eye to fresh attention. They exist in a sphere of experience that is too exhausted to change. Because worn-out people on the verge of passing out can only stand so much, a reliable, blandly inoffensive appeal is the key to survival.

The original Tonight Show already possessed the core components of nearly all late shows to come. There was the host, his scripted topical monologue, his semi-scripted interstitial patter. There were famous people for him (and it was always him) to interview. There were musical acts from guest performers. People from the studio audience were occasionally heard from and seen. Sometimes there would be bits recorded outside the studio. But the most rigid and least adaptable elements of late-night television were none of these: They were, rather, the house band and the theme song it was compelled to repeat at the beginning of each show. It’s no accident that Allen resorted to sonic imagery to describe the genre he was inaugurating. Music, after all, is the most time-tested way of passing time while sustaining some, but not all, interest. If the function of late-night shows is to set a pace and then repeat it into oblivion like a lullaby, then music, which is nothing if not structuring time, is likely to serve as the foundation in a form where reliability is everything. Few things can be more reassuring than knowing that the same band is there to play the same song at the same time. Ever-changing yet ever the same, the band and song spell out the premise, and promise, of late shows as a whole.

Late shows aren’t completely impervious to transformations. How could they be when they attract comedians, a species of humanity that trains itself incessantly to mock anything before it? Garry Shandling created The Larry Sanders Show, a behind-the-scenes dramedy which endowed late night with the plot and character development it normally lacked. David Letterman’s charm was predicated on his weary, offhand knowledge of the ultimate pointlessness of the late-night enterprise. There was Arsenio Hall, the first black man with a late-night show, who enlivened the genre by introducing elements of hip-hop and wrestling culture. There was Conan O’Brien, who recognized the basic stupidity of late night by gleefully doubling down on it. Yet insofar as these attempts to subvert the genre remained loyal to its fundamental constraints, the change they brought tended to be reabsorbed into the general spirit of late night, with its aura of ritualized, somnolent, prolonged decrepitude. The underlying protocol — prolonged light entertainment for people slipping in and out of consciousness — remained the same. If the host’s delivery and attitude could change, the nature of the script did not, and the surest sign of this inability to break from deep conventions, was, again, the house band and the theme music, which remained as monotonous as ever.

It’s telling that the most decisive break from late-night tradition isn’t generally recognized as a late-night show at all. When David Lynch realized the latent uncanniness of the genre by blending the forms and non sequiturs of late night with the ambiance of dreams, the outcome — the paranormal Red Room on Twin Peaks with its diminutive host, special guests drawn from the dead and living, and bizarre dialogue leading nowhere — was, like the show as a whole, so aesthetically strange and compelling that it created a “late-night” paradigm all its own. The shift in musical orientation was a clear indicator that the codes of conduct typical of former late shows had been dispensed with entirely. There was music, but no band present to perform it, and the song which came from nowhere was a meditative ‘50s-vintage jazz number to which the host danced, inexplicably.

Each “episode” of the Red Room was different and unrepeatable, and the show, broadcast briefly at irregular intervals from the clock-less space of the subconscious, had no relation to the marathon format of standard late shows, with their rigid emphasis on scheduling. There was no way, it seemed, to change the late night show while remaining loyal to its conception of time, and to depart from that conception was to mutate the late show to the point where it could no longer be named a late show at all. Birds are dinosaurs, but no one calls them that.

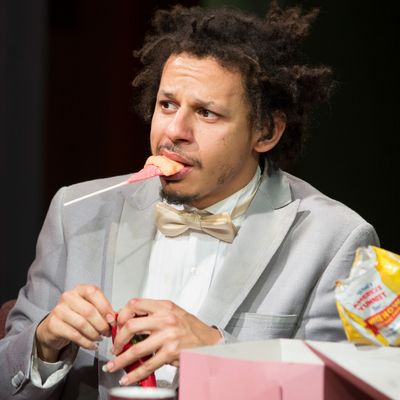

But still: What would happen if someone, despite being fully conscious of the hopelessness of changing late shows while staying a late show, tried to pull it off anyway? Eric André’s show is a program powered by its creator’s agonizing and acute awareness of both the archaic banality of late-night talk shows and the urgent need to destroy them. The show has become famous for having each episode commence with André attacking his house band (tackling the drummer, to be exact) in the process of screaming and destroying the set of his show. Yet this awareness is complicated by a clear affection for the inherent idiocy of the form and by the knowledge of how late night incorporates the revolts aimed against it by ritualizing them. The drummer is always tackled, but the percussion in the theme songs always goes on undisturbed; the set is demolished, but then everything is restored to its original condition as the host pants, slumped in a chair, exhausted by pointless labor.

The show is steeped in a venerable heritage of burned-out and co-opted insurrection. Larry Sanders’s commitment to cutting the host down to size sets a precedent for André’s bottomless capacity to humiliate himself in a variety of cringe-inducing man-on-the-street segments; Letterman’s mordant, questioning demeanor is reflected in the saturnine skepticism of André’s co-host Hannibal Buress; Arsenio’s willingness to make a place for hip-hop artists is matched and exceeded by André, a black man whose roster of interview guests is largely comprised of mediocre non-rap celebrities and excellent rappers. If Conan doubled down on late-night stupidity, André multiplies that stupidity by a factor of 20. The opening monologues are invariably improvised and awful, the musical performers are subjected to bizarre physical indignities, and the interview guests receive the same treatment while fielding incoherent questions. Discomfort and disruption seem to be the only norms.

The comparisons with Brechtian disturbance and Artaudian cruelty are as obvious as they are accurate, but André’s show resonates most deeply with the theatrics of David Lynch. With its basement lighting, uncannily awkward figurants (for example, a bike-helmeted and Velveeta-shaded character named Kraft Punk), and unpredictable host, The Eric André Show is the first late-night show to register the influence of Twin Peaks’ iconic crimson-colored chamber. (The show went so far as to parody the show directly when André shot his co-host several times and initiated a murder mystery titled Who Killed Hannibal? complete with haunting theme music and theme-music montage.) Standard late-night shows deploy music to soothe and sedate; Eric André uses music to estrange and (sometimes literally) shock. The host doesn’t just introduce musicians, but indulges in music himself. One of the highlights of the first season was an opening monologue that consisted of André and Buress in white clothes singing a ballad whose nonsense lyrics cite Chiquita Banana, Osh Kosh B’Gosh, Obama, and love; a highlight of the recent season consisted of André and Buress trading early-’80s-style basic raps which concluded in Buress jovially zooming off onto a tangent about the ‘90s-era children’s show Bobby’s World.

If the show is the first of its kind to internalize the improvised timing and delivery of rap, it’s also the first to internalize rap’s political orientation, whether latent or blatant: Its deranged exteriors conceal a sharpness regarding public affairs unmatched by any other show on air, late-night or otherwise. The Chiquita Banana song sums up both the spirit of conciliation inspired by Obama’s first election and that spirit’s ultimate absurdity; André’s insanely pointless interview questions are very occasionally punctuated by a completely serious and important question about drone warfare or Louis Farrakhan’s anti-Semitism and involvement in Malcolm X’s murder. And André’s deeply obnoxious and alienating public behavior (sometimes done while impersonating a policeman) takes on an aspect of suicidal insolence and bravery when one considers how black Americans have been murdered by the police for even the slightest and most spurious deviation from public order: the fake gunshots liberally used on the show are lethally echoed in real life.

No small part of André’s frantic impatience with the changelessness of late-night shows is rooted in an association of the genre’s formal conservatism with the social conservatism of the nation at large, and when the year’s iconic moment among standard late shows was Fallon’s cravenly tolerant interview of Trump, his former fellow NBC host, it’s an association that’s hard to deny. When the audience of “normal” late shows tends to be old and white, and old and white are two of Trump’s strongest demographics, the odds against changing late shows for the better can seem as astronomical as the odds of improving the nation. (André’s show is one-quarter of the length of The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon; people of color make up one-quarter of the American population.) André, for his part, seems well aware of what time it is. The most drastic change in season four of The Eric Andre Show was musical, but it was also demographic: The friendly, multiracial, variously dressed house band of former seasons was replaced by a team of old white men in identical white suits, whose leader had a tendency to glower at the host.