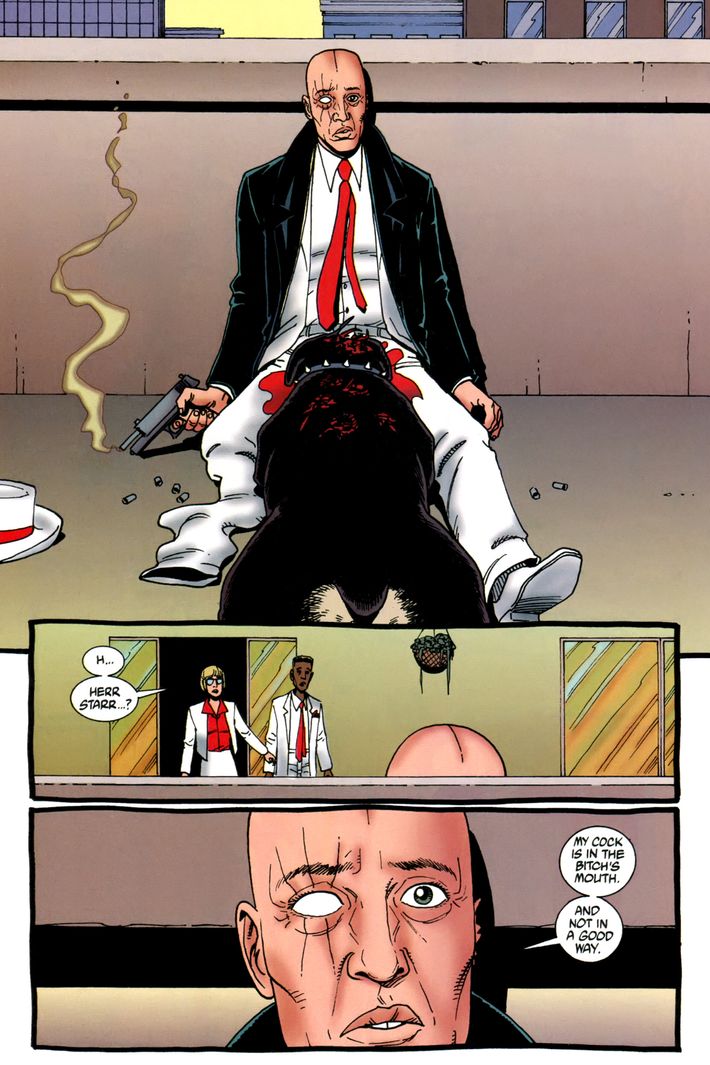

A few weeks before Preacher debuted on AMC this spring, I interviewed Seth Rogen, one of the showÔÇÖs executive producers and, due to his fame, the public face of its promotional effort. He, like me, had spent many days of his teenage existence poring over the comic-book series that inspired the TV show. One of the great comics of the turn of the millennium, Preacher was written by Garth Ennis and penciled by Steve Dillon, the latter of whom died yesterday at the age of 54. ÔÇ£What moments do you remember striking you the most when you first read Preacher?ÔÇØ I asked Rogen during the interview. He paused for a second. ÔÇ£Herr StarrÔÇÖs dick getting bit off by a dog,ÔÇØ he replied.

IÔÇÖd just finished rereading PreacherÔÇÖs 66-issue run a few days prior, but even if I hadnÔÇÖt seen that image since IÔÇÖd first laid eyes on it 15 years prior, I wouldÔÇÖve been able to recall it without effort. In a square panel that occupies more than half-a-page, Starr ÔÇö the perpetually ill-lucked sociopath who travels the world to chase PreacherÔÇÖs protagonists ÔÇö sits slumped against a guard wall on a rooftop after a bloody fight. He wears a dashing trench coat and a crisp suit. At his lap is the corpse of a dog heÔÇÖs shot, one whose jaw is still clamped around the remnants of his genitals. He stares toward the reader, not quite making eye contact, and his face contains an expression lying somewhere triangulated between wonder, horror, and total resignation. Upon first seeing it, you shriek as hard as you smile. The panel contains no words:

With Dillon, as with all the great comics artists, you often didnÔÇÖt need dialogue. Over the course of his 38-year-long career, one that was kicked off at the age of 16, the Englishman became one of the finest artists the medium had ever seen. Yet, at the same time, he was rarely the most talked-about. All too often he was taken for granted, in no small part because he wasnÔÇÖt flashy. As comics professionals and critics have been noting in their tweeted tributes, one of his gifts was his ability to lay out a scene in a way that was deceptively simple: He moved narratives along with such clarity of perspective and organization of physical objects that you hardly noticed his hand guiding you along. Other superstar pencilers of his generation made their reputations through art that was mind-bending and abstract or grandiose and bombastic. Dillon occasionally dipped into that sort of work ÔÇö his demonry and explosions were top-notch ÔÇö but that wasnÔÇÖt what set him apart. What Dillon did better than just about anybody was tell stories using the human form.

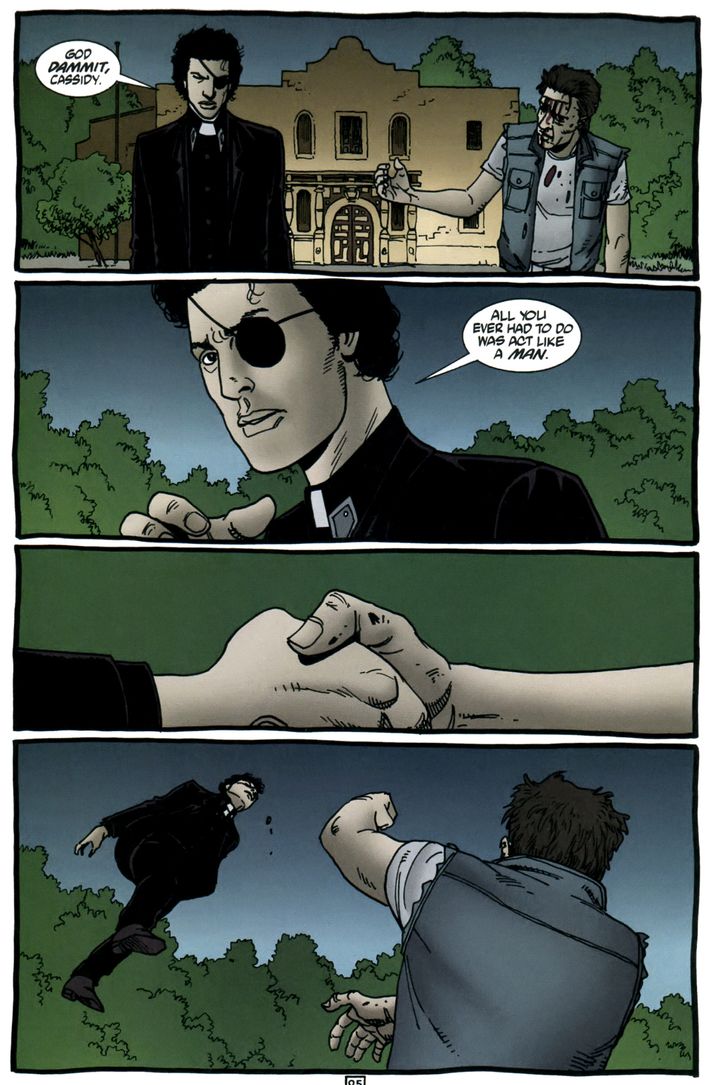

If we were to deploy a cinematic metaphor, Dillon was exceedingly good at cinematography, but he was unparalleled at directing, if you will, his characters. He conjured body language and facial expressions that could break your heart, crack you up, or make you gasp. I could try to describe what IÔÇÖm talking about, but itÔÇÖs better to show than to tell. That dick-dismembering scene Rogen and I are so fond of (above) is an example of his black-comedic gifts; if you want pathos, try this moment, in which female lead Tulip confronts erstwhile comedic lead Cassidy after heÔÇÖs spent months drugging and raping her. Note the way TulipÔÇÖs face crawls up from exhausted determination to slight-but-triumphant satisfaction:

For ecstasy, hereÔÇÖs a flashback to CassidyÔÇÖs awe-struck arrival in America in the early 20th century (heÔÇÖs an immortal vampire, which explains his lack of aging between this page and the last one):

And hereÔÇÖs one of my favorite depictions of a fight. Near PreacherÔÇÖs conclusion, main protagonist Jesse does battle with Cassidy, whose vampirism gives him superhuman strength. Look at the rhythm with which Dillon depicts the sceneÔÇÖs physical motion: boom, one manÔÇÖs hand rises for an apparent peace-making handshake; boom, so does the otherÔÇÖs; boom, they entwine; ka-boom, a crackling sucker-punch. What makes that last panel so impactful, literally and figuratively, is the fact that it doesnÔÇÖt show the instant of contact or any speed lines to convey how JesseÔÇÖs body has moved. He is just as surprised as the reader to find that heÔÇÖs suddenly in midair. The violence is jaw-dropping because itÔÇÖs so simple:

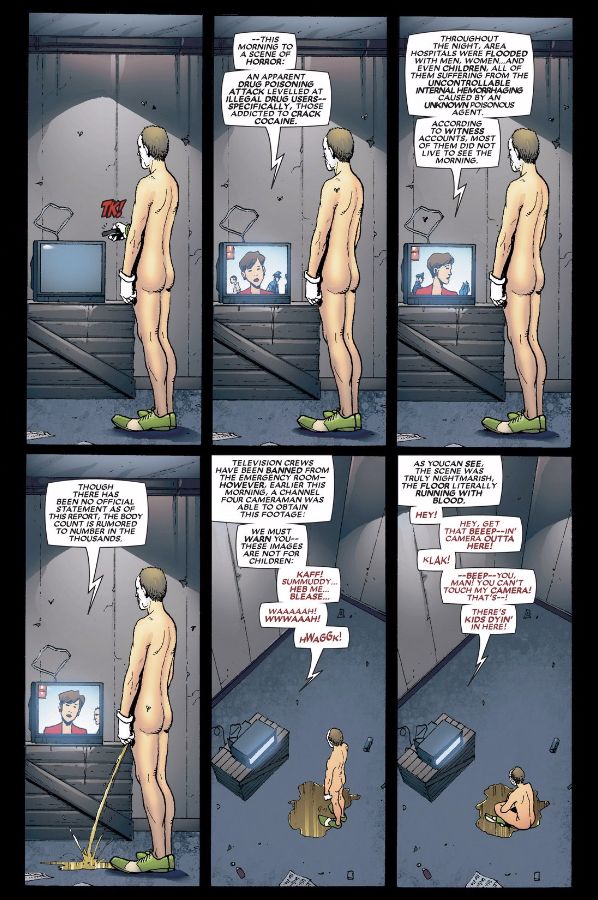

ThatÔÇÖs all just from one series. Although Dillon wasnÔÇÖt the most prolific creator, he was dependably stunning. He cut his teeth in the venerable U.K. comics-anthology 2000 AD, where he placed himself in the pantheon of great Judge Dredd artists. He made himself a star in the U.S. by illustrating DC ComicsÔÇÖ Hellblazer during a stretch written by Ennis, who would go on to be his greatest collaborator. He and Ennis moved to Marvel and crafted a set of ripping Punisher yarns, one of which featured what is easily Western artÔÇÖs greatest depiction of a man punching a polar bear. IÔÇÖm a huge fan of one of DillonÔÇÖs least-discussed works: a miniseries about C-list Marvel anti-hero Nighthawk. I still have nightmares about a scene in its third issue where a serial killer watches the news naked while dispassionately pissing on a concrete floor, then sits in the warm puddle:

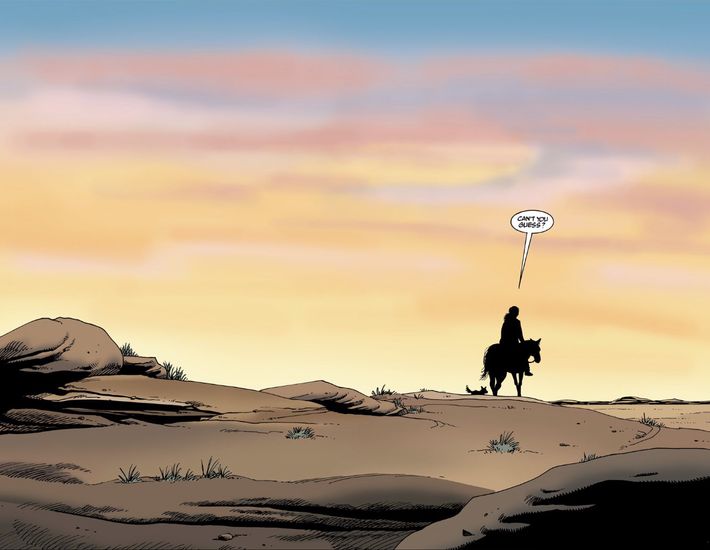

Most recently, Dillon had returned to his longtime muse, the Punisher, for a delightfully grim run alongside writer Becky Cloonan; he was also drawing covers for EnnisÔÇÖs bawdy Sixpack and Dog-Welder: Hard TravelinÔÇÖ Heroz at DC. Though itÔÇÖs a tragedy that he was taken so soon, we can take some small comfort in the knowledge that he lived long enough to see his most famous work get translated to television as part of the comics-adaptation boom. ÔÇ£We donÔÇÖt gotta let ourselves be lessened by death or any other damn thing,ÔÇØ Jesse tells Tulip in PreacherÔÇÖs final issue. ÔÇ£We can make our lives the way we want them ÔÇö or we ainÔÇÖt worth nothing.ÔÇØ Steve Dillon was worth a hell of a lot.