Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

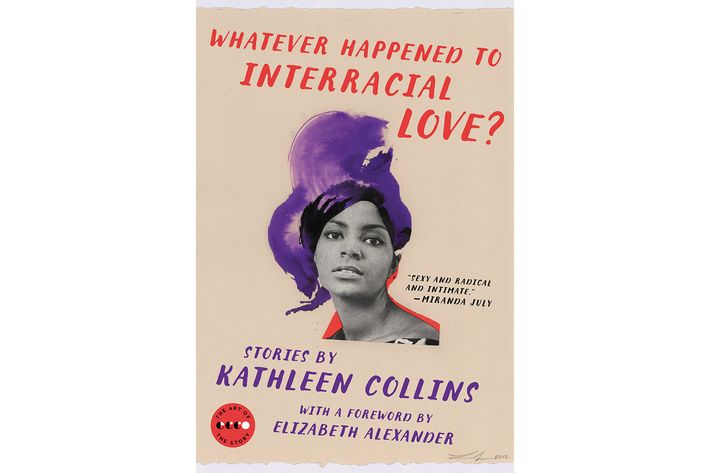

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, by Kathleen Collins (Ecco, December 6)

A groundbreaking African-American playwright and filmmaker who died young in 1988, Collins was known (if at all) for her 1982 comedy-drama Losing Ground. Few people knew she also wrote prose ÔÇö until now. Published for the first time, some of these stories borrow from the language of drama (stage and lighting directions) to illuminate psychological states. The title piece follows a round robin of interracial couples at painfully close range. Throughout, Collins explores families coming together and apart, buffeted by both an imperfect society and destabilizing forces of a more personal kind.

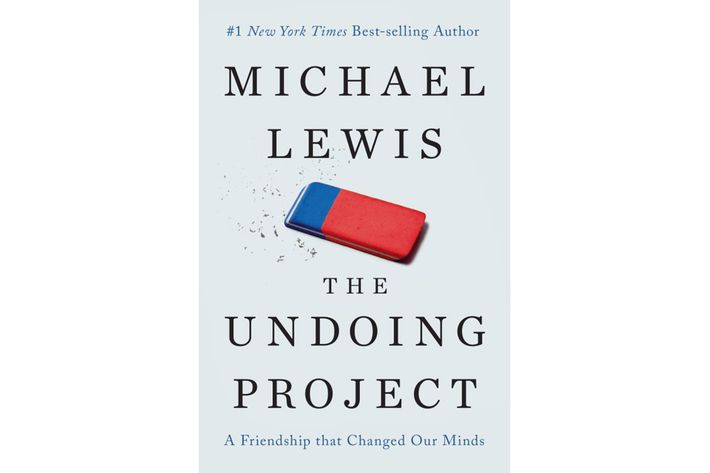

The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Lives, by Michael Lewis (W.W. Norton, December 6)

LewisÔÇÖs long-gestating passion project about Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, the pioneers of behavioral economics, predated The Big Short, but in light of recent events it seems just as timely as that indictment of the financial psychosis that led to the Great Recession. The pair of psychologists, whose rocky relationship helps structure the story, wrote a series of papers showing just how faulty our intuition is ÔÇö how prone to confirmation bias and information bubbles. They changed economics forever (and Kahneman won a Nobel for that); human behavior has proved a little more stubborn.

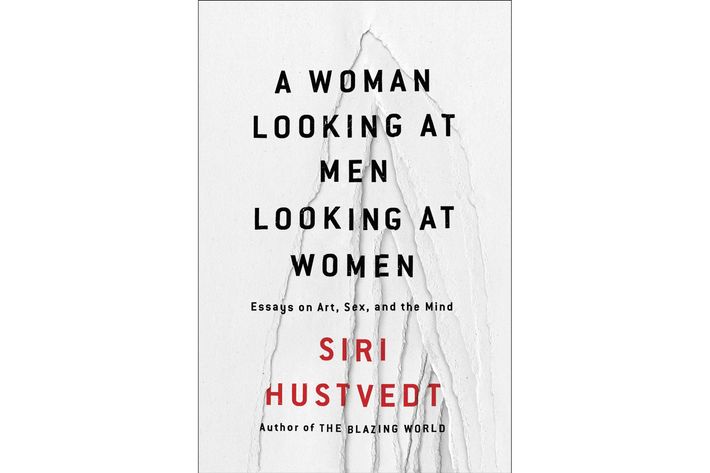

A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women: Essays on Art, Sex, and the Mind, by Siri Hustvedt (Simon & Schuster, Dec. 6)

Come to this collection for the crystalline art criticism, analyzing gender through the prism of Picasso, Koons, Mapplethorpe, and Louise Bourgeois and deepening HustvedtÔÇÖs fixation on women and art (as seen in her last novel, The Blazing World). Stay for essays on the mind-body problem and a strong takedown of trends in pop psychology (Steven PinkerÔÇÖs essentialism; the worship of brain scans). No single reader will warm to every essay, but unlike many genre straddlers, Hustvedt doesnÔÇÖt pander or patronize. Her erudite essays are unlikely to draw more readers to her fiction, but they should.

The French Revolution: From Enlightenment to Tyranny, by Ian Davidson (Pegasus Books, December 6)

More than 200 years later, the worldÔÇÖs first true working-class revolution is little-enough understood that a new, nuts-and-bolts history, subtly but importantly reframed, feels essential and sadly all-too-relevant. The overthrow of the old regime began as an earnest, American-style attempt to enshrine the rule of law. But for a few big mistakes and economic privations, it might have gone much better, especially for some 35,000 heads. The terror that followed feels inevitable today, but Davidson shows that it wasnÔÇÖt. Then and now, communal self-destruction is preventable and maybe even foreseeable.

The Gardens of Consolation, by Parisa Reza, trans. Adriana Hunter (Europa, December 6)

The Iranian-French authorÔÇÖs debut juxtaposes IranÔÇÖs rural roots with its explosive urban history in the story of one humble family that travels across the divide. In the middle of the last century, a shepherd and his wife move from the remote village where they fell in love to suburban Tehran and raise a son, Bahram, who excels academically. As the old government falls and a new Shah rises, Bahram becomes enmeshed with nationalist politics (and philandering) while his simple parents cling to a beautifully described life they thought would never change.

Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White, by Michael Tisserand (Harper Collins, December 6)

The many artists influenced by HerrimanÔÇÖs seminal Krazy Kat comics may not realize how much history, political and personal, is packed into those panels. Among the undercurrents in HerrimanÔÇÖs art are his own little-known origins: Born to black Creole parents in New Orleans, he passed successfully for white. Feted by Woodrow Wilson and other not so racially enlightened types, he snuck his own experiences into his work in ways that require unpacking by a diligent and searching biographer. Tisserand tracks not only HerrimanÔÇÖs cross-country travels and evolving art but also the rapid growth of a conflicted nation.

The Private Life of Mrs. Sharma, by Ratika Kapur (Bloomsbury, December 13)

The first-person peregrinations of Renuka Sharma, a Delhi woman left to scrimp and dream with her teenage son while her husband tries to make good in Dubai, reveal both a wry, honest voice and a perceptive witness. Against the backdrop of IndiaÔÇÖs modern contrasts ÔÇö high-end bars flush with nouveau wealth, crumbling infrastructure and a dwindling middle class ÔÇö the lonely, practical wife grows close to a man she meets at a train station. The possibilities and ultimate consequences seem as inevitable as the global realities that fence her in.