This week, Vulture is taking a look at great unproduced, unreleased, or unheralded entertainment.

When talking about great movies that never got made, save a special place at the table for Michael MannÔÇÖs Gates of Fire, an epic about the Battle of Thermopylae that the filmmaker was attached to direct in the early 2000s. The film, based on Steven PressfieldÔÇÖs 1998 historical novel, was to have been a realistic and intense look at the ancient warrior kingdom of Sparta and their doomed but historically momentous attempt to hold off the invading Persians at Thermopylae. Does that sound familiar? Probably, because Zack SnyderÔÇÖs 300 is about that same battle ÔÇö but that film pales in comparison to the promise that Gates of Fire held as an immersive, historically detailed, brutal, and elegiac war movie by one of AmericaÔÇÖs greatest directors, working at the height of his powers.

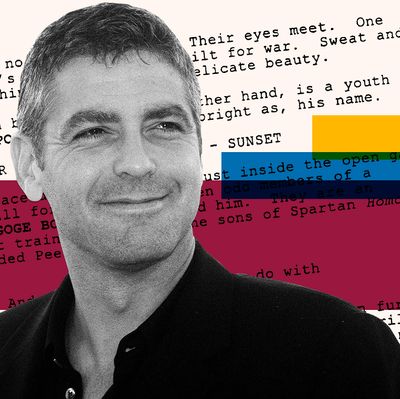

The film rights to Gates of Fire were purchased in January 1998 ÔÇö months before the novel even came out ÔÇö by Universal for George ClooneyÔÇÖs production company Maysville Pictures, with Clooney himself set to produce and possibly star. David Self (Thirteen Days, Road to Perdition) was hired to write the script, and Mann circled the project in late 1999, becoming officially attached in early 2000. The stars seemed to be aligned: The director was riding high on the success of the Oscar-nominated The Insider. Clooney, whose film career had once seemed moribund, was coming off the acclaimed Out of Sight (1998) and Three Kings (1999). In the summer of 2000, Gladiator came out and tore up the box office. The filmÔÇÖs path seemed to be clear; Clooney said in an interview with Movieline magazine late in 2000 that Bruce Willis was constantly hounding him for a part.

A draft of SelfÔÇÖs screenplay that IÔÇÖve read suggests that, indeed, it would have been a hell of a movie. Gates of Fire follows the experiences of Zeones, or Zeo, a Greek boy from the small city of Astakos whose family is wiped out by Argive soldiers in the storyÔÇÖs early scenes. Looking to find a bigger city to call his own, he winds up in Sparta. (ÔÇ£They say other cities make temples and palaces. They say Sparta makes men.ÔÇØ) He winds up as a servant to some young Spartan warriors, among them Alexandros, a callow youth struggling in the shadow of his father, the great warrior Dienekes. As SpartaÔÇÖs King Leonidas struggles ÔÇö often violently ÔÇö to unite the Greeks against the impending invasion by the Persians, we get lots of insights into the elaborate, militaristic rituals of the Spartans, the ways that they effectively torture each other in order to prepare for battle. We also get to learn about the brotherhood of these men. Little is known about the historical Sparta, but SelfÔÇÖs script is filled with seemingly authentic details (many of them taken from PressfieldÔÇÖs acclaimed novel, which to this day is taught in military schools in both the U.S. and abroad). The depiction of war is gruesome, chaotic, and vividly imagined ÔÇö filled with tactical maneuvers and moments of what would surely have been intense, almost unbearable physicality.

It would have been an interesting choice for Mann, whose Last of the Mohicans, from 1992, is probably one of the all-time-great historical action films. But by the early 2000s, he was a changed filmmaker. He had begun to work more with handheld cameras and fractured perspectives in The Insider (1999) and Ali (2001), the latter of which he was hard at work on when he signed on to do Gates. The Greek epic, had it gotten off the ground, might have made for an ideal mix of the Mann of Mohicans and the Mann of later years, for even though Zeo is the ostensible protagonist of Gates, perspective is not limited to just one character.

Unfortunately, the film would have been very expensive to make ÔÇö around $175 to $200 million dollars, which was real money back then. It was in active development for several years, but no casting decisions appeared to have been made. Clooney had a couple more hits (The Perfect Storm, OceanÔÇÖs 11) and spent much of 2001 and 2002 making his directorial debut, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind. After Ali turned out to be something of a critical disappointment (we were all wrong about it back then, but I digress), Mann released the smaller Collateral in 2004 and went right to work on Miami Vice.

But perhaps more important, a couple of similarly themed historical films went bust in the meantime, including Oliver StoneÔÇÖs Alexander and Wolfgang PetersenÔÇÖs Troy, both released in 2004; the following year saw the disappointment of Ridley ScottÔÇÖs not-at-all-similar but often-mentioned-in-the-same-breath Crusades epic Kingdom of Heaven. Mann departed over ÔÇ£creative differencesÔÇØ sometime around 2005. But what truly appears to have killed Gates of Fire dead as a project was the 2007 success of 300, Zack SnyderÔÇÖs adaptation of Frank MillerÔÇÖs comic book about Thermopylae. 300 producer Gianni Nunnari said that he had tried to buy the rights to Gates of Fire back in the day; when he found out theyÔÇÖd already been sold, he went about trying to find other material about the historical event, and landed on MillerÔÇÖs 300, a smaller-scale picture that wasnÔÇÖt going to blow through any studioÔÇÖs budget.

Of course, who knows what would have happened had Gates of Fire actually been made. Maybe the diffuse nature of the story and the characters would have overwhelmed Mann. Maybe the gritty approach to Greek warfare would not have been as successful with audiences as the comic-book aesthetics of 300. But even if Gates had flopped, it might have still been historically momentous: Like the brave, doomed Spartans at Thermopylae who lost their lives but still managed to hold off the Persians long enough, the film might have kept Zack Snyder from making 300. Which in turn might have also had the fringe benefit of keeping Zack Snyder from eventually becoming the man entrusted with the DC Extended Universe of films, an arrangement that currently seems to be a source of frustration for critics and audiences alike. Woulda coulda shoulda; film history is filled with promising projects that might have been, which might have then led to, or prevented, other projects. Consider: The film Wolfgang Petersen was working on when he decided to go do Troy instead? A little thing called Superman vs. Batman.

Bilge Ebiri is a film critic for the Village Voice. He was previously a film critic for Vulture.