Binge-watching is easy; just drag the laptop into bed and go. But savoring a book of, say, 800 pages or longer is a project. No book that size is perfect, because excess is kind of the point. What marathon runner doesnÔÇÖt curse the universe or even get bored once in a while? That doesnÔÇÖt negate the rush of endorphins or the thrill of mastery. If you power down your iPhone and power through to the end, one of these books might change your life.

Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes (1605, 976 pp.)

The novel and the satire were born at the same time in this series of misadventures befalling the romance-besotted mad knight errant and his sane sidekick. The nested stories are very much rooted in post-medieval Spain, but the pratfalls are timeless; self-delusion knows no cultural barriers.

Bleak House, by Charles Dickens (1853, 960 pp.)

The great English novelist, here at his most grown-up, doesnÔÇÖt do lawyers any favors. Following the money, he uses a single lawsuit over a dwindling inheritance to expose societyÔÇÖs role. But this is still Dickens: funny, heartfelt, and redemptive.

War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy (1869, 1,296 pp.)

On top of everything else the Russian master accomplished in this historical novel about the Napoleonic era in Russia, he really nailed the title. By shifting focus from the battlefield to the home front and back, he captured the total effect of war on armies and aristocrats, husbands and wives.

Middlemarch, by George Eliot (1872, 880 pp.)

Eliot was a world-builder in the classic sense; her fictional Middlemarch is an English town like many others, exemplary of bourgeois mores and the site of many parallel plots. The epic is made ordinary, and vice versa.

The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1880, 824 pp.)

EuropeÔÇÖs original existentialist might have gone darker in┬áCrime and Punishment, but he captures a larger universe here, from the portrait of a family whose members achieve Christly heights and Trumpian lows to cerebral set pieces that would blow most novellas out of the water.

In Search of Lost Time, by Marcel Proust (1913ÔÇô1927, 4,215 pp.)

It isnÔÇÖt cheating to say that ProustÔÇÖs series is really a novel. Even more than a few others here, this is a unified work ÔÇö gorgeously written, recursive but not repetitive, and profound even when chronicling the shallowest of socialites.

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia, by Rebecca West (1941, 1,181 pp.)

Interest in WestÔÇÖs book, a category-killer in several categories (travel book, cultural history, memoir), revived during the Balkan wars in the ÔÇÿ90s ┬áÔÇö which is appropriate for a book written on the eve of Nazi invasion. But as a wholly engrossing, never-flagging work of poetic journalism, itÔÇÖs always worth reading.

The Man Without Qualities, by Robert Musil (1943, 1,744 pp.)

If MusilÔÇÖs colossus of philosophical and social fiction seems to peter out, thatÔÇÖs because he never finished it. But dissipation of the novel, whose title character is a reflective blank, mirrors the decadence of Viennese society around World War I ÔÇö prosperous, rule-bound, beautiful, and doomed.

The Lord of the Rings, by J. R. R. Tolkien (1955, 1,178 pp.)

The trilogy is available in single volumes and best read that way. The pioneer of modern fantasy was also its perfecter, because he knew what it meant to create a universe. A professional linguist, Tolkien didnÔÇÖt just invent; he used everything heÔÇÖd learned and made it new.

Life and Fate, by Vasily Grossman (1959, 896 pp.)

Though often compared to┬áWar and Peace, the long-suppressed World War II novel has more in common with war journalism, which Grossman practiced as a Soviet reporter on the front. He emerged from bloody battle with both a great story and a sly critique of the centuryÔÇÖs two great monsters ÔÇö Hitler and the one at home.

The Power Broker, by Robert Caro (1974, 1,336 pp.)

Before he embarked on his multivolume biography of Lyndon B. Johnson, Caro wrought justice on Robert Moses, cementing the uber-bureaucratÔÇÖs reputation as a destroyer of New YorkÔÇÖs urban fabric in a masterpiece of very longform adversarial journalism.

Shogun, by James Clavell (1975, 1,192 pp.)

A triumph of research and plot over character and subtlety, ClavellÔÇÖs historical novel about an Englishmen who goes native with the first Japanese shogun is the first among equals of the James Michener era of middlebrow informational epics.

Canopus in Argos: Archives, by Doris Lessing (1979ÔÇô1984, 1,228 pp.)

This may the deepest dive into sci-fi (Lessing called it ÔÇ£space fictionÔÇØ) that any Nobel PrizeÔÇôwinner has ever attempted ÔÇö five linked novels telling the universeÔÇÖs secret history in the stories of interrelated planet-civilizations. Come for the fiction, not the science.

The Stand, by Stephen King (1978/1990, 823/1,152 pp.)

The original edition of KingÔÇÖs apocalyptic moral fable and the ÔÇ£Complete and UncutÔÇØ updated version both have their partisans. Good and evil are complicated but simply drawn, as in his more typical horror fiction. But given the space, King excels at texture. Which is to say, if youÔÇÖre in for 800 pages, you might as well go uncut.

The Pillars of the Earth, by Ken Follett (1989, 816 pp.)

Like Lessing and King, suspense writer Follett went for broke in a genre new to him. Like the groundbreaking (and fictional) Gothic cathedral that rises in the course of his 12th-century-British historical work, the best seller soars, sprawls, and brims with humanityÔÇÖs gargoyles.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame, by Victor Hugo (1833, 940 pp.)

Pairs well with The Pillars of the Earth.

A Suitable Boy, by Vikram Seth (1993, 1,349 pp.)

SethÔÇÖs story, which follows one familyÔÇÖs search for their daughterÔÇÖs perfect match but also IndiaÔÇÖs transition from feudal colony to partitioned mega-state, is so vast that it requires not one but four family trees in the front. Yet his language is unadorned and accessible; nothing gets in the way of the story.

Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace (1996, 1,079 pp.)

Somehow the most difficult and the most approachable four-figure-page book youÔÇÖll read, WallaceÔÇÖs monumental compendium of dystopia, comedy, tennis, drug recovery, and high-impact footnotes has been alternately under- and overrated for 20 years. It wonÔÇÖt likely be forgotten.

Underworld, by Don DeLillo (1997, 827 pp.)

Probably the best very long novel of the last century, itÔÇÖs a Great American one, too, and a pure distillation of New York, from its home-run opening (the ÔÇ£Shot Heard Round the WorldÔÇØ that won the Giants the 1951 pennant) to the glories and horrors of the then-present day, which is where that winning baseball ends up.

Shantaram, by Gregory David Roberts (2004, 936 pp.)

Bombay and bombast reign in RobertsÔÇÖs fictionalized account of his escape from an Australian prison to India, where, in swashbuckling scene after narrow escape, he is tortured, sexed up, and enlisted in a gang of Afghan gunrunners. Who cares how much itÔÇÖs true, or literary? Even when unintentionally funny, itÔÇÖs enormous fun.

2666, by Roberto Bola├▒o (2004, 912 pp.)

The structure of the late pan-Latin authorÔÇÖs magnum opus is deviously simple ÔÇö the mystery of a writerÔÇÖs identity explored in five ÔÇ£Parts.ÔÇØ The first is playful, about literary academics; the fourth is a deliberately numbing catalogue of gruesome murders. Across all chapters, the sentences beguile and the story devastates.

Against the Day, by Thomas Pynchon (2006, 1,086 pp.)

A glorious mess in a career of glorious messes, PynchonÔÇÖs longest and loosest novel floats and careens along with the Chums of Chance ÔÇö the crew of a time-traveling interdimensional airship that becomes embroiled in a Western revenge story, a Siberian disaster, and the invention of thermodynamics. DonÔÇÖt ask ÔÇö just read.

Sacred Games, by Vikram Chandra (2007, 928 pp.)

ThereÔÇÖs a kind of reader who gets off on the juxtaposition of a gripping genre plot and an indecipherable dialect. It may not be the common reader, and ChandraÔÇÖs detective-noir-on-steroids-in-Hinglish failed to meet too-high sales expectations. ThatÔÇÖs too bad, because the near-apocalyptic payoff is well worth the effort.

1Q84, by Haruki Murakami (2011, 928 pp.)

AmericaÔÇÖs favorite Japanese writer on American-pop themes has earned the right to go big in this deep, indulgent dive, featuring a semi-fantastic world with two moons, an assassin, and a ghostwriter on a collision course, and a cult that may or may not be evil. Love it or not, itÔÇÖs pure, uncut Murakami.

The Neapolitan Novels, by Elena Ferrante (2012ÔÇô2015, 1,682 pp.)

The once-anonymous Italian novelist considers her four books ÔÇö mostly about two female friends living divergent lives in patriarchal, violent, stratified Naples ÔÇö to be a single novel, so we should too. Never mind the authorÔÇÖs identity; the cycle is a womanÔÇÖs enduring testament to art, life, and realism.

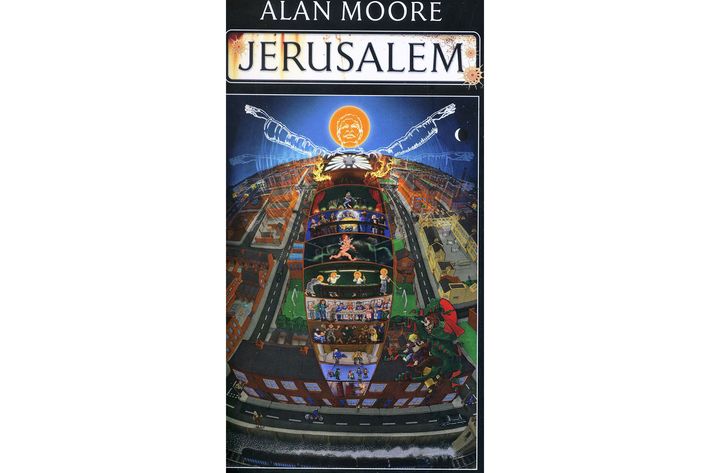

Jerusalem, by Alan Moore (2016, 1,280 pp.)

If you canÔÇÖt decide between a modern version of┬áFinneganÔÇÖs Wake, a cranky essay collection by a beloved comic writer (Watchmen┬áet al.), the 2,000-year history of an English micro-neighborhood, the cosmic adventures of a child ghost, a narrative poem, or dozens more fever dreams of a maniacal genius, read them all here.