Michael Shannon is pretty sure he doesn’t have walking pneumonia, but whatever’s going on in his body seems cause for genuine concern. He’s shuffling along the sidewalk in downtown Manhattan like a goon’s taken a crowbar to his legs, his towering six-foot-three frame hunched and swaying, his words coming out in the foggy haze of someone who was still at the bar when the sun came up. This isn’t actor histrionics; “that’s just the way I walk when I’m tired,” he says. “I’ve literally been hearing that for over a decade, that people think I’m limping.” His fatigue was so pronounced on the set of Nocturnal Animals, the dreamlike thriller (in wide release December 9) in which Shannon plays a West Texas police detective bent on justice and with nothing to lose but the phlegm in his cancer-ridden lungs, that director Tom Ford — yes, the fashion designer — wondered if one of his legs might be longer than the other.

It’s a miracle Shannon is standing at all, given that he’s in eight movies coming out this year — including not one but two films with his most frequent collaborator, Jeff Nichols: March’s sci-fi saga Midnight Special and the prestige drama Loving. Plus he’s got two more in the can, and another, Guillermo del Toro’s top-secret Cold War fantasy adventure The Shape of Water, that he just finished shooting in Toronto at 4 a.m. in the rain less than 48 hours before we meet, which is why he looks like he’s about to die. Granted, he wasn’t even physically in one of those movies: In Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, the corpse of his dead villain character, General Zod, is seen in a body bag and naked in a pool of water. “You think that was me lying there? That’s a piece of rubber! They built that!”

Many of Shannon’s 2016 appearances are brief, sometimes just a day’s worth of shooting, but he’s a secret weapon any director would be thrilled to drop in for two scenes to turn the intensity dial up to 11. If the Academy Awards gave out a statue for Most Supporting Actor, he’d be the favorite.

He’s also acquired new fame as a meme of liberal America’s angry id, with his biting quotes from recent interviews — of elderly voters he said, “If you voted for Trump, it’s time for the urn” — going viral. He wasn’t mincing words when we met, either, the Saturday before the election: “I don’t know if these people are stupid or not, but it’s certainly a huge con! It’s just very strange that people derive hope from the personage of Donald Trump, because Donald Trump is devoid of hope. He’s a black hole. He is a soulless, evil piece of shit.”

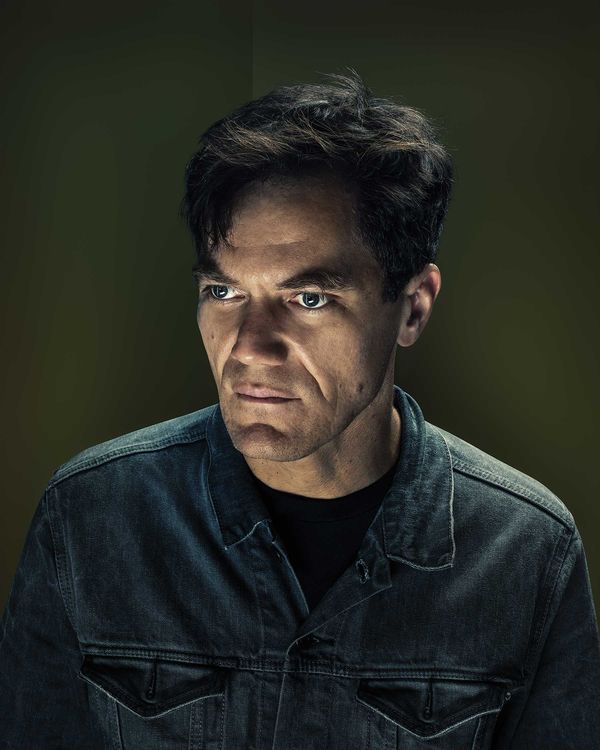

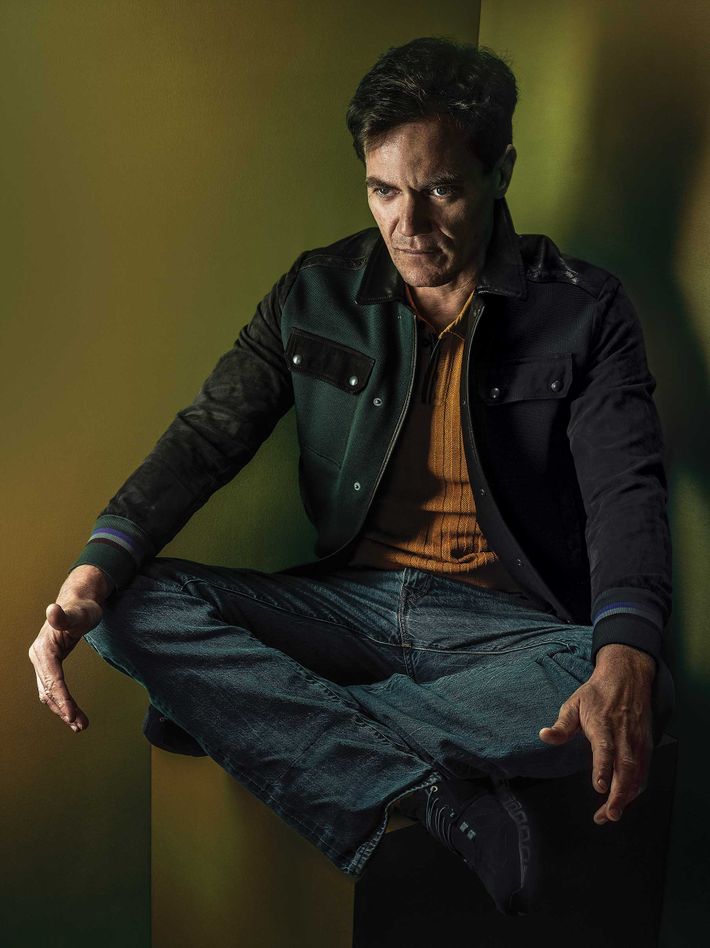

Today, the 42-year-old has on a jean jacket with MIDNIGHT SPECIAL stitched on the back; he’s been wearing it nonstop ever since he got it as a wrap-party gift two and a half years ago, in brazen disregard of the unspoken actor rule that it’s super-embarrassing to wear your own swag. (“I’m still promoting it!” he declares. “I like this jacket so much, and I love that movie.”) This year, Shannon showed up at the Toronto Film Festival’s fanciest party in a Hawaiian shirt, jean shorts, sneakers, and colorful socks, of which he’s been a collector for years. “I find the tyranny of fashion surrounding the entertainment industry kind of silly,” he says. “It’s not like you’re at a funeral. It’s a party!”

Shannon can come off as gruff, with that face of hard-won creases and his remarkable restraint in never laughing at your jokes or making eye contact — which is just as well, since the few times I meet his steely-blue gaze, it feels like he’s shooting eye-lasers straight into my soul. Yet he’s also a deadpan riot who keeps me laughing for two hours straight. “People make him out to be this scary guy, and I know that’s something he fights with,” says The Girlfriend Experience’s Paul Sparks, the only actor Shannon says he hangs out with in New York. Later, I learn he’s also friends with Michelle Williams, his Red Hook neighbor. Shannon lives above the Fairway Market and is often down there getting groceries, but he says his favorite time living above the legendary supermarket was after Hurricane Sandy, when it got flooded and closed for four months.

Physically, he’s an intimidating presence, so much so that when Nichols asked a casting director to find him someone like Shannon for the first film they did together, 2007’s Shotgun Stories, she brought in a bunch of bar bouncers. (Shannon, who ended up in the role, has been in every one of Nichols’s five films.) And as long as he’s got a reputation as a big, terrifying guy, he might as well have fun with it. Sparks remembers watching him haze a new director on Boardwalk Empire, on which Shannon spent five seasons playing zealous Prohibition officer turned murderous bootlegger Nelson Van Alden. The nervous director came over and asked him to do the take a different way. “And Mike says, ‘You want me to cry?! Let me understand, you want me to cry?!’ ” says Sparks. “Loud enough where everyone could hear him, where the whole set stopped, like, ‘Oh, no!’ And he sort of let [the director] toil in it for a while, and then he said, ‘Oh, I’m just fucking with you.’ That’s very, very Mike.”

A self-described angry child of divorce raised in Lexington, Kentucky, Shannon came up through the Chicago theater scene. He caught the movie world’s attention, and a supporting-actor Oscar nomination, playing a truth-telling psychopath in 2008’s Revolutionary Road. But both before and after that, he had a Bill Murray–type approachability. He’s been known to grab a beer with civilians who came to see him at the tiny Barrow Street Theatre in the West Village, where he originated Bug in 2004, played the stage manager in the famed black-box production of Our Town in 2010, and spent 90 minutes talking to himself and a goldfish in the virtuosic one-man show Mistakes Were Made later that year.

“I’ll be in charge!” says Shannon as he leads me on a spontaneous tour of Soho and Tribeca. We pass by City Winery, where Shannon had played with his alt-folk band Corporal (he writes songs and does vocals, keys, and guitar) the night before at a fund-raiser for the real-life inspiration of his 2011 movie Machine Gun Preacher, a vigilante rescuer of South Sudanese orphans. “I feel like what I did the majority of the evening was take pictures with people on their cell phones, which is my least favorite thing to do outside of things that are actually physically painful,” says Shannon. He usually says no because he hates iPhones. What kind of phone does he have? “It’s irrelevant,” he says. But anyway, “the main thing I’ve noticed about the iPhones is that, inevitably, you’re having a conversation with somebody and then they say, ‘I gotta show you this picture!’ And then they’ve got so many pictures on their phone they can’t even find the picture they’re looking for!” I do eventually get to see his phone, which is one step up from a flip phone and does take grainy pictures, his favorite of which is of a bag of pizza dough he bought at Fairway.

We turn onto a small side street. “I was gonna show you where it all started,” he says, taking me to the (unfortunately locked) door of the Soho Playhouse, where in 1998 he had his first paid acting job in New York, originating the role of inept drug dealer Chris in Killer Joe, by Tracy Letts, the playwright friend who also wrote for him a juicy part as a paranoid Gulf War veteran in Bug. “He just has this mercurial quality that makes people want to see what happens next,” Letts says of Shannon. Nichols has a theory why: “I believe Mike is a raw nerve,” he says. “He is so receptive to the world around him that sometimes it almost seems like it physically hurts him. And I think a lot of what people read about him as being stoic or gruff, it’s actually quite the opposite. He bristles at life because it affects him more than normal people.”

Jessica Chastain tells the story of how during Take Shelter, Nichols had gotten a bunch of locals to be extras by offering them a fish supper but hadn’t told them what was coming. All of a sudden, Shannon flipped over a table and erupted into a monologue about the apocalypse, “and at the end, all the extras clapped because they forgot they were in a scene!” says Chastain. “People were like, Holy shit, is he gonna hurt me?” Nichols adds. “Also, he’s throwing coleslaw on them.”

Shannon is a loyalist who tends to work with the same people over and over again: Letts; Nichols; James Franco (appearing in two student films he directed, having sex with Franco in one and with a corpse in the other); and Werner Herzog, whom he’s worked with three times, including on next year’s bizarre eco-thriller Salt and Fire, filmed on the breathtaking salt flats of Bolivia. And directors seem to love Shannon right back. Tom Ford, for one, is obsessed with his volatile, dying lawman in Nocturnal Animals. “He is the Marlboro Man. He is Gary Cooper in High Noon,” Ford writes via email. “He is an archetype of something that exists in cinema history. On one take, when I put the mustache on him, I said, ‘You know, you’re kind of Clark Gable. I would really be interested to see what you would be like as a romantic leading man.’ ” Shannon actually did have two romantic leads this year, opposite Rachel Weisz in Complete Unknown and Imogen Poots in Frank & Lola, plus a few self-hating sex scenes on Boardwalk. “I’m making my way into porn! The ultimate goal!” he says. “Just trying to prove myself.”

He takes me to his favorite Middle Eastern spot, 12 Chairs, but it’s too crowded (“I knew 12 Chairs when it was just 12 chairs! And there were only four people in it!”), so we head to a kitschy Mexican diner, Lupe’s, where he orders a margarita and starts making pained faces and rubbing his neck up against the wall. “I’m so sore,” he says. “My body’s having all sorts of sensations.”

Does Shannon ever think about awards? “Well, I’d better win a damn Oscar if you’re putting me in the Oscar issue! It’s about damn time, Jesus!” he says, though he’s not planning on campaigning for Nocturnal Animals, which is probably his best shot. He’d rather be like Mark Rylance last year; skip the handshaking, just be too good to ignore.

Shannon checks his old-school phone. He’d promised he’d go home and play with his daughters. But if someone wants to throw him an award, sure, go for it. “I’m just always kind of bewildered by it, because I look back at my life and where I come from and the fact that I’ve gotten to this place, to be in this position,” he says, “and it just never ceases to amaze me.” And with that, he limps away to the next thing.

*This article appears in the November 28, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.