The Museum of Modern ArtÔÇÖs retrospective of the radically unquantifiable, relentlessly original Francis Picabia is a blast of fresh air just when we need it. Picabia is a freedom machine. He tears down pretentions and turns painting into something animal, making it almost uncomfortable to look at. His anti-rationalistic art of sincerity fused with ironic self-consciousness (we still donÔÇÖt know if Picabia really means any of it) rouses us from our familiar clannish feedback loops that may have left us comatose in this moment bordering on the tragic. Picabia wakes the polis.

Who was Picabia? On some level it is astonishing that anyone would have to ask. Born wealthy in Paris in 1879, Picabia is a crucial co-inventor of five of the most far-reaching movements of the 20th century ÔÇö Cubism, Dada (which he broke with), Surrealism (which he renounced), abstraction, and postmodernism. Provocative from start, he claimed to have made perfect copies of the art in his parentÔÇÖs home, selling the originals and replacing them with his own work. Picabia was smash success by the age of 26, called ÔÇ£a masterÔÇØ for his stiff Impressionism. The next year, he was showing internationally; the year after that brought the first monograph on his work. Revolutionary until the day he died, a bon vivant and ladiesÔÇÖ man who often had overlapping wives or mistresses all living and traveling together, he said the ÔÇ£phallus should┬á have eyesÔÇØ to see ÔÇ£love up close.ÔÇØ (Put eyes inside the vagina as well and who could not love him!)

ItÔÇÖs not easy to generalize about what his work looks like since what really characterized his life was his overwhelming aesthetic restlessness. Picabia is the least know of the great modern masters. His animalistic unwillingness to be caged into any style or ism, his ÔÇ£canÔÇÖt step in the same river twiceÔÇØ insistence on constant artistic flux makes Picabia the Heraclitus-like God of Change of Modern Art. He said ÔÇ£the only movement is perpetual movementÔÇØ; called isms ÔÇ£absurd trafficÔÇØ; espoused a continuous ÔÇ£revolution in tasteÔÇØ; asserted that anything not modern has ÔÇ£no reason to exist.ÔÇØ Importantly, he refused to see art as a career, calling painting movements and isms the ÔÇ£paintocracy.ÔÇØ

This is all especially pertinent in our time, when success is foregrounded, an expected narrative that often gets in the way of real novelty and invention, replacing it with consensus. Everyone knows how to act, what to think. Familiar appropriation seems played out. How many more artists will claim ÔÇ£these two objects I put together create a narrativeÔÇØ? Recent all-over process painting already feels as far away as Obama. The idea that something might be ÔÇ£good political artÔÇØ just because it has Trump in it but doesnÔÇÖt rupture any formal infrastructure is the avant-guard sleepwalking. PicabiaÔÇÖs wild weirdness, his insistence on taking every medium and material seriously, not just as an anti-art prank, and expanding it into new ideas of virtuosity, feels much closer to us. I sometimes think that if every artist took just one tiny thing from PicabiaÔÇÖs paintings, poetry, graphic design, film, or drawing, any of these things could be scaled up, distorted, and transformed into larger visual systems and structures. This seems pressing when so many of our familiar institutions and infrastructures have failed us.

His inventiveness is dizzying. At MoMA, before youÔÇÖve even left the first gallery of Impressionist works, come giant brownish abstractions from the early teens. This is his most well-known art. But because he wasnÔÇÖt then in its power narrative, MoMA didnÔÇÖt get around to collecting him until the 1950s. These wildly structured Cubist compositions are like the optical walks of a mad astronomer charting a new pictorial cosmos. Arcing, orbiting shapes break and curve into almost-recognizable forms, blooming into still lifes, landscapes, people ÔÇö all under centrifugal pressure, whirling toward the surface or swirling into psychedelic space. PicabiaÔÇÖs structure is akin to some abstract ant colony organizing everything according to an unknown tectonics that all work together. This is Cubism as hive.

Then, presto, the Cubism is gone. By 1915, Picabia must have beheld another morphology and spatial organization at work in his art and evolved his hives into images and portraits of machine parts, spark plugs, windows, things that look like space stations, high-tension towers, pistons, kitchen tools. This is Picabia abandoning the ÔÇ£paintocracy,ÔÇØ deploying industrial design, drafting techniques, and advertising art with no pretense at fussy painterly verities. When he was attacked for these, he said, ÔÇ£Copying apples, thatÔÇÖs understandable to everyone, but copying a turbine, thatÔÇÖs stupid.ÔÇØ You mightnÔÇÖt have noticed it, but in this gallery youÔÇÖve just witnessed the invention of Dada. Here are works where he had people sign their name to his canvass. This is the alluring cave-like graffiti painting which also appears on the cover of the showÔÇÖs catalogue. It takes a village to make art like this, many minds oriented toward a queen ÔÇö in this case Picabia. Elsewhere, a picture frame is strung with four strings and three pieces of butcher paper, with either his signature, title, or the words ÔÇ£Rat Tobacco.ÔÇØ Painting as weaving, test site, store-window adornment, stripped to bare minimums but still crashing on our minds. ThereÔÇÖs even a picture of a stuffed monkey nailed to a board, titled Portrait of Cezanne. And he loved Cezanne. This is an artist in overflow, never settling. Again, something that seems germane right now.

You are at a crucial point in the show ÔÇö maybe in your thinking about art today ÔÇö where you mustnÔÇÖt fall into the typical Duchampian-Dada art-world rabbit hole that so many have gone into and never come out of (a.k.a., many art schools and curators). Despite 100 years of academic insistence, Picabia is not just some fun ironist, clown, or nihilist who believes in nothing. What Picabia believes in is right there on the surface of his work. You canÔÇÖt risk this much, push so hard, experiment so widely, or stare down internal and external skepticism without really believing in your instrument ÔÇö in this case, art. Rather than seeing him as an antic artist, see Picabia as an early embodiment of Jimi Hendrix playing the national anthem ÔÇö experimenting, using distortion, shifting modalities of internal structure; stretching an utterly known form into new configurations and finding things hidden there; manipulating our master inner tape; making this known thing new, dangerous, bawdy, beautiful; mining essences previously unrepresentable and suddenly essential. Picabia can blow you away.

This is borne out in the miracle of the rest of the show. Miles Davis once told Greg Tate, ÔÇ£If youÔÇÖre playing their music youÔÇÖre wasting your time.ÔÇØ From here on, Picabia plays his own music. His ideas of style, scale, authorship, subject matter, materiality, narrative, composition, touch, color, technique, and surface mushroom into undiscovered incunabula for artists. Picabia has mad skills, but heÔÇÖs always willing to engage in what looks like amateurish Sunday pleasure painting. This breaks all the tribal codes and makes for paintings that fit in no category, except being strong, optical, seductive, smart. He makes still lifes, portraits, and beach scenes using matchsticks, hairpins, coins, string, straw, and noodles. These are classical subjects in new materials that break free of classicism and reconnect to art from different anti-esoteric vectors. He finds in kitsch a lifeboat away from too much good taste. But again, this isnÔÇÖt an anti-art, nihilist, sinking-ship gesture of futility. ItÔÇÖs a mutiny ÔÇö┬ásomeone becoming his own captain, assuming control. This is another beacon in a time looking for effective ways to take agency.

From this point in the show forward, I recommend looking at everything from close up. As close as one dog might sniff another. This will stop you from worrying about ÔÇ£What does this mean?ÔÇØ Instead behold one of the most vertiginously voluptuous, hallucinatory techniques and surfaces in the 20th century. Nothing this cultivated, earthy, burning with inventiveness and intention, dripping with sensibility, and full-bodied love of paint could be mistaken for ironic joking. The surface of Portrait of a Woman, a knotty little dark picture of a outlined face, has a gorgeous surface of cheetah-like spots, moir├®s of cracks and fissures, colors caramelizing, sluices and geological topographies. It looks like itÔÇÖs been varnished a hundred times, coated in molasses or hydrochloric acid, left in the rain, then baked in the sun. I see paint in formation, thought finding form, beauty turning as fabulous as fashionable fabric. This is PicabiaÔÇÖs Hendrix-like experimentation in all its anthemic glory packed into the density ÔÇö not of a few minutes ÔÇö but a few square inches.

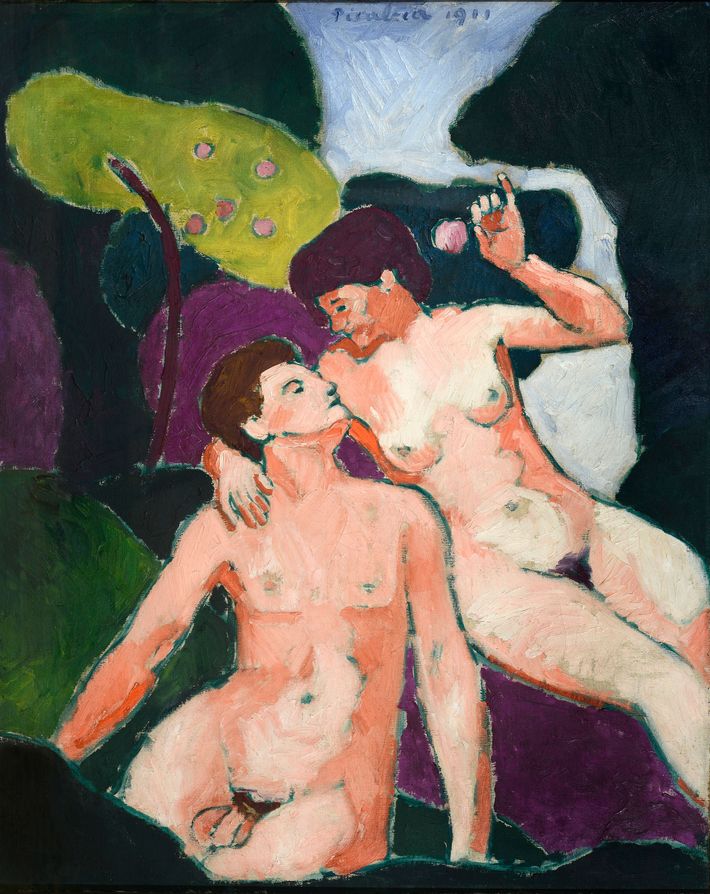

And Picabia only keeps inventing. In the late ÔÇÿ20s, he reimagines pre-Renaissance art in his overlays of transparent images of figures, flowers, saints, and lovers. Late medieval art often encapsulates different events on one surface ÔÇö so that you see an annunciation and the later birth combined with one another, and your mind unwinds them and places them in a new space. Cezanne and the Cubists did this with single forms seen simultaneously from different angles. Picabia introduces filmic ideas of montage, cuts, and sequencing in his see-through, outlined images. In Young Girl in Paradise, you look through two almost Byzantine angels at a woman with a flower in her hair ÔÇö an archetypal flamenco dancer or descendant of GoyaÔÇÖs Maja ÔÇö and through her to a desert on fire. A whole world forms that allows the mind to look into and around the surface, beholding everything at once ÔÇö as with Cubism ÔÇö but also broken down into separate elements and events ÔÇö as with medieval art.

We owe it to Picabia, art, and ourselves not to cast these multiple narratives, times, and simultaneous spaces as an art joke. This witchcraft explains what the title of this show alludes to, his saying that ÔÇ£Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction.ÔÇØ This show is a possible course correction and call to mutiny.