WeÔÇÖre looking for clues. What art and which artists had inklings we were entering a paradigm shift? Who was already channeling that in their work? Peering through aesthetic lenses of hindsight to the turnabout of political authority, conflicted posturings, hidden narratives, and changes in moral code, we see human Geiger counters who were making art that gleaned the doors of chaos suddenly being held ajar.

1. Rob Pruitt, ÔÇ£The Obama PaintingsÔÇØ

Gavin Brown Gallery (ongoing)

For every day of Barack ObamaÔÇÖs two terms in office, Rob Pruitt made one small painting of the president based on a photograph found online, in a newspaper, wherever. Installed wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling, even stacked in bins, these 2,800-plus paintings are an extended act of unironic love, dedication, and discipline. If kept and displayed together, ÔÇ£The Obama PaintingsÔÇØ would fit in perfectly in the future Obama presidential library ÔÇö a reminder that not so long ago, power and beauty intertwined.

2.┬áÔÇ£Open PlanÔÇØ and Danny Lyon

Whitney Museum

Five fantastic short-term shows appeared over three months, each using the WhitneyÔÇÖs huge open fifth-floor space and giving us great art and the kind of experimental thinking weÔÇÖve already come to rely on from this reborn institution. Bonus: ÔÇ£Open PlanÔÇØ was followed up by a stellar survey of photographer Danny Lyon.

3.┬áMarilyn Minter, ÔÇ£Pretty/DirtyÔÇØ

Brooklyn Museum (ongoing)

No one nails the nexus of bawdy sex, gaudy beauty, gorgeous surface, and electric, eye-popping color like Marilyn Minter. Her works are giant history paintings of women flaunting forms of political and visual being in mid-change.

4. Arthur Jafa, Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death

Gavin BrownÔÇÖs Enterprise

This seven-minute film of famous black figures and violence against the black body is a visual exorcism and a psychic gut-punch ÔÇö and as powerful a film as any made in this decade.

5.┬áMyla Dalbesio, ÔÇ£You Can Call Me BabyÔÇØ

James A. Farley Post Office

A rowdy, smart, anti-hegemonic show of strong work by women, curated by a woman, in the upstart art fair Spring/Break (organized by a woman) that put all sorts of new, world-changing audacity on display.

6.┬áÔÇ£DicksÔÇØ

Fortnight Institute

This tiny DIY East Village storefront space run by two supersmart young women staged ÔÇ£Dicks,ÔÇØ consisting of pictures and sculptures ÔÇö including a plaster cast of Jimi HendrixÔÇÖs member ÔÇö of penises, mostly created by women. The show did all this without showboating ÔÇö only pointing (or giving) a highly charged political finger at male myth, dickishness, and the power structure.

7. Glenn Ligon, ÔÇ£We Need to Wake Up Cause ThatÔÇÖs What Time It IsÔÇØ

Luhring Augustine

The perfect bookend to Arthur JafaÔÇÖs sped-up filmic masterpiece of the black body, LigonÔÇÖs show gives us a silent deconstruction of one of Richard PryorÔÇÖs performances ÔÇö making visible the magic dance that was always going on with this epic genius of American culture.*

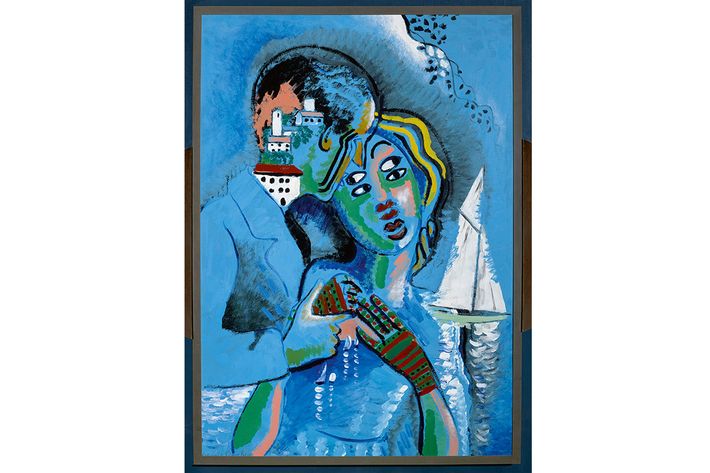

8.┬áFrancis Picabia, ÔÇ£Our Heads Are Round So Our Thoughts Can Change Direction,ÔÇØ and Kai Althoff, ÔÇ£And Then Leave Me to the Common SwiftsÔÇØ

The Museum of Modern Art (current)

Picabia is one of the artistic-freedom machines of the 20th century, and ÔÇ£Our HeadsÔÇØ is delivered in full in this perfect retrospective. It only makes matters juicier to see this show exhibited next to the metaphorical insides-of-an-artistÔÇÖs-brain survey of Kai Althoff.

9.┬áCameron Rowland, ÔÇ£91020000ÔÇØ

Artists Space Exhibitions

Cameron Rowland made the act of simply displaying ready-made objects ÔÇö like the sort of bench made by prisoners and used in courthouses by those charged with crimes ÔÇö into mind-bending Boschian paradoxes of our justice system.

10.┬áÔÇ£Golden Eggs,ÔÇØ organized by Alissa Bennett

Team Gallery

Thank goodness the art world is populated by brilliant people like Alissa Bennett, a curatorial seer of the first rank and ultrasmart director of the ultraexcellent Team Gallery who organized a summer group show of graphically direct, materially exquisite work ÔÇö all of which prefigured the awful shock and awe of Election Night.

*An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Glenn LigonÔÇÖs piece was filmed in slow motion.