Martin Scorsese has evidently waited his entire life to direct a saga of martyrdom and Judas-like betrayal on the scale of Silence, his stark, portentous adaptation of Shusaku Endo’s novel about Portuguese Catholic priests who get put through the wringer (along with their native followers) in 17th-century Japan. The movie is impressive. Scorsese isn’t working in his usual busy late style, which is meant to make you say, “Can that man cook!” He’s in the self-abnegation mode of The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun, shaking off the accumulated layers of film-consciousness in an attempt to make you see things as no one has before: with pity, terror, and — maybe hardest of all to induce — a gnawing ambivalence. It’s challenging in ways that go beyond watching violence committed against the flesh.

His protagonists are two young padres, Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Garupe (Adam Driver), who travel to the Land of the Rising Sun in search of their mentor, Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson). The older priest is rumored to have become an apostate, renouncing Christ while his fellow priests were singed, mutilated, and crucified. It’s even possible that Ferreira invented the ultimate test to determine if someone has successfully shed his or her belief: the fumi-e, an image of Christ on a stone or board onto which the believer must stomp.

Rodrigues and Garupe understand that Christianity — which had been tolerated for a time — has been driven underground by the shogun and his grand inquisitor. But they have no way of knowing the depth of the cruelty they’re about to encounter — the men and women rolled in straw mats and burned alive, or lashed to crosses and smashed by waves for days on end, or lowered headfirst into pits with cuts above their ears to allow their blood to drain, drop by agonizing drop. Perhaps even worse from the priests’ abstract perspective is that the very idea of Christian martyrdom will be called into question.

The first half of Silence is about what you’d expect if you’ve seen enough films with Japanese torturers. (Unbroken didn’t break its hero, Louis Zamperini, but it broke me.) But we begin to sense a rift opening up between the priests. Garupe is unmoving in his faith, while Rodrigues visibly blanches when he hears the dying men and women speak of paradise in the afterlife. Given God’s resolute silence, Rodrigues doesn’t seem so sure. For Endo, true (as opposed to blind) faith is impossible without a large (and even potentially crippling) measure of doubt.

It’s in the movie’s second half that things get odd. The argument against Christianity is advanced by the elderly Inquisitor Inoue, played by Issey Ogata with a laughing-clown face that suggests a Kabuki Bert Lahr. The tree of Christianity withers in Japanese soil, he says, to which Rodrigues responds that the soil has been poisoned. But what do Rodrigues or his fellow missionaries know about that metaphorical Japanese soil? Raised a Christian, Endo felt a schism in himself between his religion and the culture and mores of his country. His protagonists in Silence are Christian outsiders because that’s what he felt like.

The wild card in Silence is the Judas figure, Kichijiro (Yosuke Kubozuka), a filthy, slobbering wretch who became an apostate and then watched his entire Christian family die, and who now hurtles between mewling obeisance and the drive to betrayal. Beginning with Mean Streets, Judas has loomed large in Scorsese’s work. With Silence, he’s working toward his own Gospel of Judas. Doesn’t the Christ story carry within it the idea that man must sin before he can be saved? What if God expects man to fail?

It’s likely some audiences will have trouble with the last part of Silence, unused to hearing that the Christian missionaries with whom they’ve been identifying operate as much out of colonialist arrogance as true devotion. They’ll doubtless prefer the doubtless Thomas More of A Man for All Seasons, who sentenced hundreds of Protestants to be burned and beheaded but stuck to his principles and became a saint. To be fair to those audiences, it’s easier to dramatize certainty than ambivalence, and books like Endo’s can chart internal tug-of-wars more lucidly than films — even films with narration. Some members of Japan’s Catholic community denounced Silence when it was published, and the movie will generate a fair amount of controversy, too. Excellent!

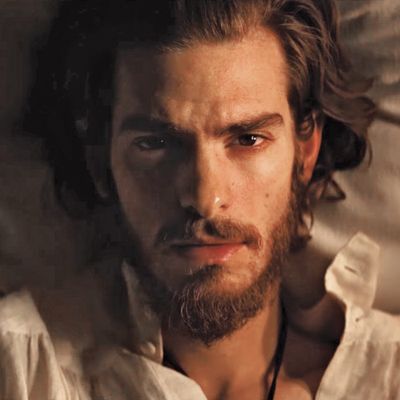

What won’t be controversial is the poetry and economy of Scorsese’s filmmaking, the chiaroscuro intensity of Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography, and the sublimity — a word that encompasses both beauty and horror — of the coastal settings where men and women meet their deaths. The contrast between Garfield’s and Driver’s visages could hardly be more powerful: the first with small, fine features, the second with outsize protuberances worthy of Goya. Given his starring role as a conscientious objector in Hacksaw Ridge, this is the second time in the last two months in which Garfield has found himself courting religious martyrdom amid extreme carnage, his face a mask of suffering. He has hereby earned the right to do two or three lousy but high-paying rom-coms without a peep of complaint.

*This article appears in the December 12, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.