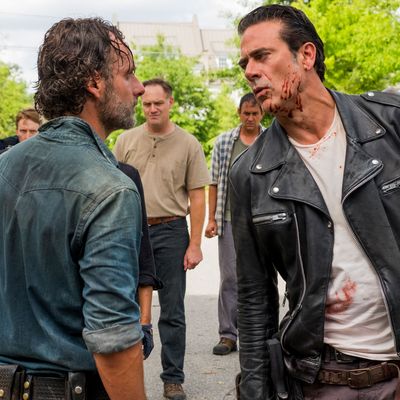

As 2016 stumbles to a close, the acceptable pathways for talking about the politics of pop culture are as well-beaten as the skull of one of Negan’s enemies. “Talk Show Host EVISCERATES Politician.” “Show X Has a Y Problem.” Discussions of cast, character, and creator diversity. But one of television’s most prominent franchises has a fundamental and frightening ethical flaw that has been left to fester.

The show is The Walking Dead. The flaw is fascism.

For years, both TWD and its spinoff series, Fear the Walking Dead, have portrayed survival in the post-apocalypse as a triumph of the will — a state of constant conflict in which the preservation of “our people,” however they may be defined, is paramount. The preservation of this in-group, and the destruction of all who threaten it, both living and dead, is the ultimate moral end. This end justifies — even necessitates — the most brutal means at each group’s disposal. Trusting others, treating others with mercy, is all but invariably portrayed as weak, stupid, self-destructive. In a world where the only moral barometer is survival, TWD establishes a binary in which the only choice for Rick Grimes and his fellows is to kill or to be killed, to slaughter or to be slaughtered. To put it in terms familiar to our president-elect, deal from strength or get crushed every time.

The similarity between the ethos of The Walking Dead and that of the Trump campaign did not go unnoticed by the campaign itself. In a Forbes profile, Trump’s son-in-law and adviser Jared Kushner revealed that the Trump team targeted ads at TWD’s viewers based on their fear of immigration, a fear the candidate was more than happy to stoke for votes and attention. In the form of both the cannibalistic undead and the frequently just as vicious bands of survivors our “heroes” encounter, the similarities to the supposedly untamed criminal hordes pouring in from Syria or Mexico or the enemy nation of choice are unmistakable: For both the show and the future president, the only proper response is a show of force.

Which, in some ways, is par for the prestige-TV course. From The Sopranos to Breaking Bad to Game of Thrones to The Americans, the New Golden Age of Television has largely been characterized by narratives of violent conflict. What, then, separates The Walking Dead from the pack, setting it apart as uniquely characteristic of our neo-fascist moment?

“We can boil fascist ethics down to one word: Dominate,” says professor Stephen Olbrys Gencarella of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, who has taught about the show as well as written about it for the academic journal Horror Studies. “It’s true that fascist aesthetics anchor many shows and films, especially in the sci-fi and fantasy genres. And of course violence is nothing new; it’s the norm in American media. Other shows out there are hitting similar themes, and that shouldn’t surprise us given the anxieties of our times. But so many of those other shows demonstrate the consequences for violence or debate the ethical complexities of living with others who are different, or show the moral turmoil of people who enact or suffer violence. The Walking Dead is the only show that actively courts, rather than critiques, fascist ethics, and suggest that it’s the only viable solution to perceived threat.”

What do those ethics entail? “In fascist mentalities, kindness, empathy, and sympathy are seen as weaknesses, critical self-reflection is seen as a danger to security, and discussion and negotiation is seen as failure,” Gencarella says. “Existence is a tragic struggle to be won or lost.” This mentality can be traced back to the fascist Ur-text, The Doctrine of Fascism, ghostwritten for Benito Mussolini by his Minister of Education Giovanni Gentile. “The Doctrine is clear that perpetual war is the preferred mode of existing with others who are different, and especially to crush the weak in order to demonstrate that one is strong,” Gencarella says. “Fascists want the apocalypse. And the history of actual fascist movements has always been cemented by the kind of storytelling that TWD valorizes and perpetuates.” It’s this perspective, and the political doctrines likely to be appealing to those who respond to it, that the Trump campaign seemingly recognized when targeting the show’s viewers. “Watching Trump and Negan on television at the same time makes perfect sense,” Gencarella says. “I don’t say that because I think all Trump supporters are fascists. But it’s also telling that the campaign thought The Walking Dead viewers would readily equate immigration with an apocalypse for which violence is the only solution.”

The character development of various Walking Dead luminaries, from Rick to Lori, Shane to Carl, Tyreese to Morgan, Carol to Daryl, Andrea to Michonne, the Governor to Negan, bears out the show’s adherence to this doctrine. Back in season one, Rick gives an impassioned speech about how the dead have rendered the racial divide and other sources of all-too-human conflict a moot point. “There’s us and the dead,” he says. “We survive this by pulling together, not apart.”

But over the ensuing seasons, both Rick and the show itself reject this appeal to unity as foolhardy, or even deceptive: As Gencarella notes in his Horror Studies article “Thunder without rain: Fascist masculinity in AMC’s The Walking Dead,” the cannibalistic humans of Terminus, who hold Rick and his group hostage, offer a slogan of “Sanctuary for All, Community for All” as a deliberate ruse to lure fresh meat into their trap. By the time Rick’s group defeats their captors, his murderous rejection of their leader’s plea for mercy has long since become par for the course. He and his fellows have repeatedly slaughtered outside groups and berated members of their party, like Tyreese, who are reluctant to bloody their hands on both moral and practical grounds. Similar plot pathways on Fear the Walking Dead pit ruthless characters like Daniel, Maddie, and Strand against bleeding hearts like Cliff. Both shows work relentlessly to construct stories in which acts of mercy invariably result in negative, violent consequences for the in-group later down the line, consequences that could have been avoided had a hard line been taken. To cite one example, Martin, a villain Tyreese fails to kill, later returns to attack and cannibalize Bob, a member of Rick’s group. TWD and FTWD also show trust of outside groups to be almost suicidally stupid, leading directly to the triumphs of Terminus, the Governor, and their ilk.

The show’s fans — fewer than there used to be after season six’s bat-swinging cliffhanger, but still enough to put the series in the upper echelon of TV’s most-watched programs — are often quick to point out that the savage surroundings of the characters require this vicious mind-set. But even a passing familiarity with the zombie subgenre of horror, let alone non-zombie post-apocalyptic narratives like Mad Max and The Road, shows this to be bogus.

“The zombie trope in the United States emerged with the zombie-as-slave phenomenon around the turn of the 20th century, when American capitalism and colonialism led to ethical conflicts about labor and human rights,” Gencarella says. The zombie as sociopolitical critique picked up even more steam when writer-director George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead tied the trope to racism and consumerism, respectively. “For that reason,” Gencarella went on, “many zombie flicks of the late 20th century could be seen as critiques of consumerist desires, or calls for cooperation between disparate groups.”

The Walking Dead, Gencarella asserts, “is part of another shift, post-9/11, in which the ghouls fill in for presumed ‘outsiders’ to the nation — but a nation that is limited only to a worthy few.” 9/11 imagery cropped up unintentionally, and largely incidentally, in Danny Boyle’s innovative fast-zombie film 28 Days Later, made before the attacks; its sequel, 28 Weeks Later, was in essence a critique of America’s militaristic overreach in the attacks’ wake. But the opening credits of Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead remake wed the terror of its depiction of the zombie apocalypse’s first harrowing hours with pointed stock imagery and mockumentary footage of Muslims and Arabs, setting a precedent for the rightward swing of the subgenre’s “us against them” political undertones. It’s here where The Walking Dead and Fear the Walking Dead pick up: The former has adopted a narrative structure of total war between miniature nation-states, while the latter quite explicitly invokes menacing Mexicans as a threat to its core group.

Importantly, the presence of women and people of color such as Glenn, Michonne, and Carol among the “worthy few” Gencarella mentions does not give The Walking Dead a pass, despite fascism’s history of defining itself along strictly patriarchal, ethno-nationalist lines. For one thing, the show’s diversity is only skin deep: “There’s a remarkable lack of diversity in the writers and showrunners, and that manifests very clearly in themes that resonate with anxious white men and fascists,” he notes.

For another, the story itself allows only narrow, traditionally fascist avenues for the growth of characters who aren’t the male ideal. “The women who can be trusted must either be uncritical nurses to the soldier males or become just like the males,” Gencarella says. “All other versions of femininity eventually prove weak or monstrous. There’s a reason Beth was killed off, for example, after suggesting a sense of hope and literally resisting being a nurse to warriors. And for all the praise that fans heap on Carol for becoming like steel, it’s just another reminder that warrior masculinity is the only way to survive. By having token bodies, the creators get to pretend that the show somehow isn’t that limited.”

But as Gencarella points out, there’s an entire cottage industry dedicated to defusing and refuting criticism. “There were early criticisms of the show, many by critics who were women and people of color, for its lack of diversity, its tired tropes around race and gender, and its abusive inclinations, but they were drowned out by the often manufactured praise of AMC,” he says, explaining, “Talking Dead came into being specifically to coach people on how to praise the show. There’s a whole system in place to create plausible deniability around race and gender in the show.”

For whatever reason, the death of fan-favorite character Glenn in the season-seven premiere seems to have broken the spell to some extent. No doubt the way in which the show chose to tell this story — ending the previous season with the swing of Negan’s bat as a cliffhanger and not revealing its target for months, then seemingly giving Glenn a reprieve only to draw out the tension and kill him later in the episode — had much to do with the overwhelmingly negative critical and audience reaction, not to mention the show’s downward ratings drift. But the extravagant sadism with which Glenn, one of the most prominent Asian-American protagonists on television, was dispatched helped wipe away the show’s surface-level multiculturalism, revealing that the only cultural metric that matters to it in the end is the use of power to establish mastery.

Here, at least, is a glimmer of hope, one potentially borne out by the show’s ratings decline: Audiences of all political persuasions have the power to refute that cynical characterization simply by changing the channel. With the show’s hyperviolent mid-season finale now in the rearview mirror — Negan still large and in charge, Rick and his group still plotting righteous rebellion and revenge — and Trump’s inauguration the coal in everyone’s Christmas stocking, it’s worth reconsidering what visions we value in television’s political makeup. And there’s no better place to start than with TV’s biggest, bloodiest franchise.